Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

There are many things you need to keep in mind if you are embarking on a development project – one of which is building size. Depending on where you are (we’ll explain why location matters in a bit), any new build house or flat conversion could be subject to the nationally described space standard, which sets out requirements for the internal areas of new homes.

Beyond the gross internal floor area, or GIA, of a new home, the standard also sets minimum size requirements for key parts of the home like bedrooms, storage spaces and floor-to-ceiling heights. Importantly, these requirements are also linked to occupancy levels – meaning that they differ depending on how many people are meant to be living in any particular bedroom.

It is therefore essential for every property developer to understand the nationally described space standard and how it is applied across various household sizes.

We're sharing this table here so you can understand what we are talking about - but if you read on you will learn much more about its history, context and how it is used.

| Type of dwelling | Minimum gross internal floor areas (GIA)* and storage (sqm) | ||||

| Number of bedrooms | Number of bedspaces | 1-storey dwellings | 2-storey dwellings | 3-storey dwellings | Built-in storage |

|

1b

|

1p | 39/37 | 1 | ||

| 2p | 50 | 58 | 1.5 | ||

|

2b

|

3p | 61 | 70 |

2

|

|

| 4p | 70 | 79 | |||

|

3b

|

4p | 74 | 84 | 90 |

2.5

|

| 5p | 86 | 93 | 99 | ||

| 6p | 95 | 102 | 108 | ||

|

4b

|

5p | 90 | 97 | 103 |

3

|

| 6p | 99 | 106 | 112 | ||

| 7p | 108 | 115 | 121 | ||

| 8p | 117 | 124 | 130 | ||

|

5b

|

6p | 103 | 110 | 116 |

3.5

|

| 7p | 112 | 119 | 125 | ||

| 8p | 121 | 128 | 134 | ||

|

6b

|

7p | 116 | 123 | 129 |

4

|

| 8p | 125 | 132 | 138 | ||

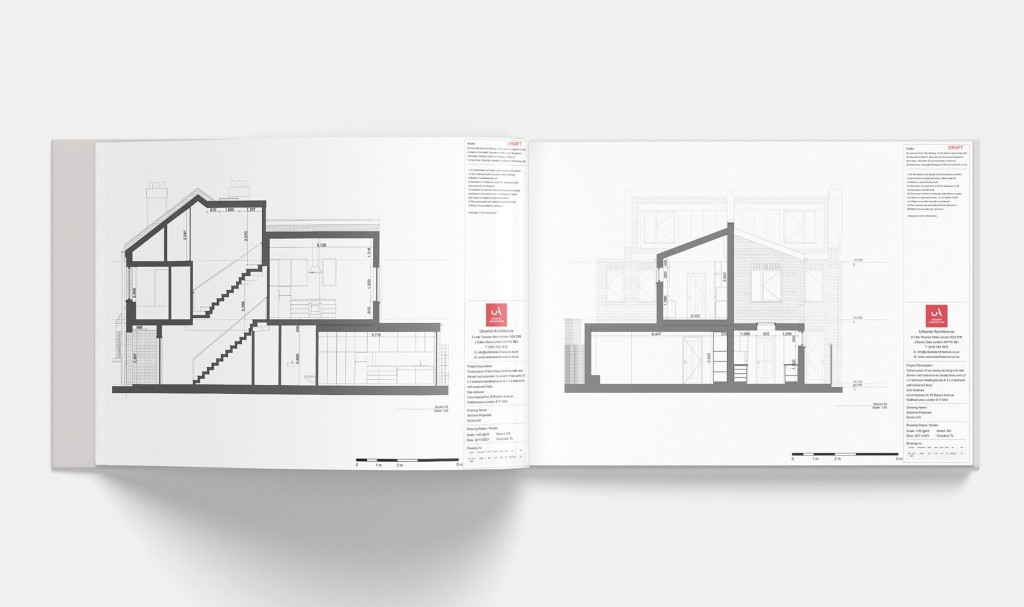

This guide will take you through the process of crafting a design proposal that complies with internal area requirements. It will also explain how these requirements contribute to a standard of high-quality housing delivery.

You will find examples on constrained sites and an explanation of how we made them work. You will also learn how to go above and beyond the requirements through clever solutions to common design challenges.

But first, let’s take a step back and consider how the technical housing standard that we now know came to be.

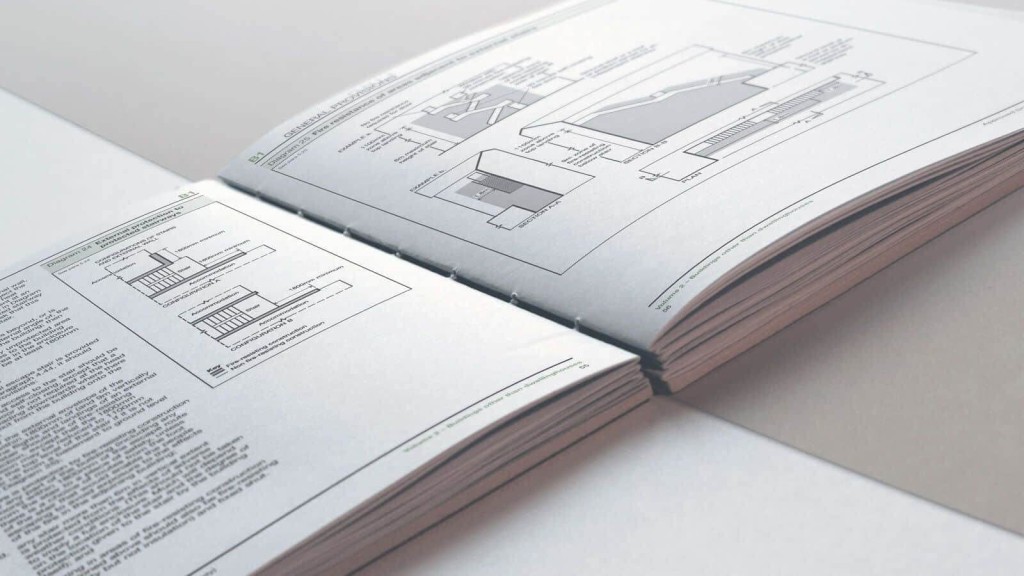

The current nationally described space standard was set by the government in 2015. However, there’s a long history in this country of attempting to regulate the internal areas of living spaces.

While the reasoning behind this has evolved, there has been a consistent understanding that the layout and spacing of homes have a significant impact on housing quality in general, and residents’ life quality in particular.

The story often begins in Victorian England, during which the early industrial period prompted the largely unregulated development of cities like London. The overcrowding of cramped, low-quality housing resulted in a number of issues, and was even believed to be one of the causes of the cholera epidemic.

Throughout the late 19th century, laws emerged to govern new housing development with the aim of reducing the spread of disease. Housing quality became a moral imperative, and by 1919 the question of floor space standards in council housing was first raised.

This time, space standards also had to do with the ideal arrangement of families, and the distinct needs of those with younger children. The 1949 Housing Manual explored the internal area requirements that were necessary for sufficient storage, cooking and study space – all of which were meant to contribute to the unity of household relationships.

The link between housing quality and social welfare has continued to underscore contemporary policy, though the extent of regulation in this sphere has varied. Following the free market boom of the 1980s, and a subsequent decline in public sector housing delivery, concerns began to rise again over the size of new housing across the country.

The nationally described space standard that we now know was informed by a 2013 Housing Standards Review technical consultation. In 2014, it was announced that this resulted in the rollout of optional requirements set out at the national level, for local authorities to decide whether or not to adopt.

That’s right – the language of a “national standard” is slightly misleading here, as the space standards laid out by national policy are actually optional, not sanctioned requirements. It is therefore up to local councils to decide whether or not to adopt the standard, based on a number of considerations.

Planning Policy Guidance recommends that local councils take the following factors into account when determining whether or not to adopt the space standard:

It’s worth noting that all councils within London ascribe to the national space standard, because it’s been adopted in the London Plan. But if your site is outside of London, there’s a chance that your council will not employ these requirements. The best way to find that out for sure is to check in their local plan.

If your project does have space standards to adhere to, you need not worry. This article will walk you through the standards that your proposal will need to meet, and share some insights that we’ve gathered from experience.

As we’ve mentioned, gross internal floor area (GIA) refers to the floor space within the external walls of one self-contained unit. Your GIA calculation can include the following:

However, GIA calculations should exclude:

The table at the start of this article shows the minimum gross internal area that a self-contained unit must have, according to the number of bedrooms and bed spaces provided.

To download the PDF version of the "Minimum gross internal floor areas and storage (m2)" table, please click here.

Minimum GIA requirements, therefore, vary depending on your property’s intended capacity – specifically, its number of bedrooms, bed spaces and storeys.

Now, let’s put that table into plain English to better understand the requirements it sets.

By definition, studio flats (technically a one-bedroom, one person flat - the term "studio flat" is not used in the standards) must be set on a single storey. Their minimum gross internal area is either 39 sqm with a bathroom, or 37 sqm with a shower room.

This must include provision for at least 1 sqm of built-in storage.

One-bedroom two-person (1b 2p) flats over a single storey must be at least 50 sqm, or 58 sqm over two storeys. They must be able to accommodate at least 1.5 sqm of built-in storage.

As for two-bedroom flats over a single storey, they either need to have a footprint of 61 sqm to accommodate three bedspaces, or of 70 sqm to accommodate four bedspaces.

And so on for the rest of the possible flat configurations listed.

If you’re starting to get the hang of the table, it’s likely that you’ll find something else intuitive: these requirements are the bare minimum that councils who have adopted the space standard should find acceptable when reviewing planning applications for new-build flats or flat conversions.

While proposals for developments that fall below the floor area requirement certainly do pass through the planning system – especially if they’re justified on other grounds – you’re likely to have a much stronger chance of success if your proposal meets or exceeds the standard.

This is why we often start our projects at Urbanist Architecture with a feasibility study, in order to explore exactly how many units are possible to reasonably propose on a site.

There are a few other numbers to keep in mind. According to the nationally described space standard, the minimum floor area of any new home should be 37 square metres.

In 2017, the government set out further internal area requirements for bedrooms in houses of multiple occupation (HMOs). These include the following:

So, in addition to checking whether or not your local council has adopted the national space standard, it’s important to see if your desired property type could be subject to any additional requirements.

After all, when it comes to flat conversions, your property’s existing GIA could determine the project’s viability.

Requirements vary from council to council – some like Barnet, Bromley and Hackney have no minimum size requirement when it comes to the original structure slated for conversion.

Others like Haringey and Hammersmith & Fulham have an original floor area requirement of at least 120 square metres.

We should note that, under the policy definition of “original floor area”, this 120 square metre footprint will be either the dimensions of the building as it stood in 1948 or those of the house as it was when new if it was built post-1948. Floor area created through extensions after 1948 therefore can’t count toward that 120 sqm requirement.

So, if you’re gearing up for a potential flat conversion, it’s best to first check your council’s size requirement for the footprint of the original house. At Urbanist Architecture, we tend to take a deep dive into the local policy around conversions, in order to determine how to navigate any additional constraints.

Ceiling height is another factor to keep in mind when considering the viability of your proposal. The national standard sets a minimum floor to ceiling height of 2.3m for at least 75% of the gross internal area. The London Plan takes this a step further by setting a minimum ceiling height of 2.5m.

An explicit standard for ceiling height was removed from the Building Regulations when they were simplified in 1985. However, in areas outside of London that have not adopted the national space standard, most inspectors will still require a minimum ceiling height of at least 2m for home extensions and loft conversions. If your room has a sloping ceiling, at least 50% of the floor area should be able to meet that 2m requirement.

Looking beyond the footprint of the structure itself, there are also guidelines to consider when it comes to amenity space available on site. The national standard does not set specific requirements for amenity space – gardens, terraces or other outdoor areas for enjoyment – but local policies often do. This is to support residents’ well-being by ensuring their access to outdoor space.

Within London, amenity space requirements are laid out in the London Housing Design Guide 2020. It states the following:

These standards have been set according to a consideration of the number of occupants, to accommodate their necessary furniture and activity space.

While there is no nationally set space requirement for communal amenity spaces, your council’s local plan and design guides will likely outline policies around shared amenity space and new development proposals. Let’s take a look at two examples, Lambeth and Barnet.

Lambeth: Lambeth’s adopted guidance and space standards state that new residential developments are required to provide either private or communal amenity space, particularly in areas that lack open space. If amenity space can’t be provided on-site, a financial contribution should be made toward off-site provision.

Lambeth has set sizes for amenity spaces according to the residence type. For example, each new-build house is required to provide a minimum of 30 sqm of private amenity or garden space.

For new developments, a minimum shared amenity space of 50 sqm is required, with a minimum of 10 sqm of private balcony space per flat.

Barnet: Barnet’s Residential Design Guidance states that every new housing development must ensure residents’ access to amenity space in the form of private gardens, communal gardens, courtyards, patios, balconies or roof terraces. And if the development is expected to have 10 or more children across its entirety, then proposals should offer appropriate ‘play provision’.

Just a few of Barnet’s requirements for proposed communal amenity space include: adequate sunlight and shade; controlled noise level in accordance with British Standards; screening from parking and public inlook; consideration of safety; availability of seating; planting of trees; and the appropriate provision of lighting, paving and footpaths.

All of these qualities are meant to contribute to an effective and affordable landscape management regime, while taking into account the needs across spectrums of age and ability.

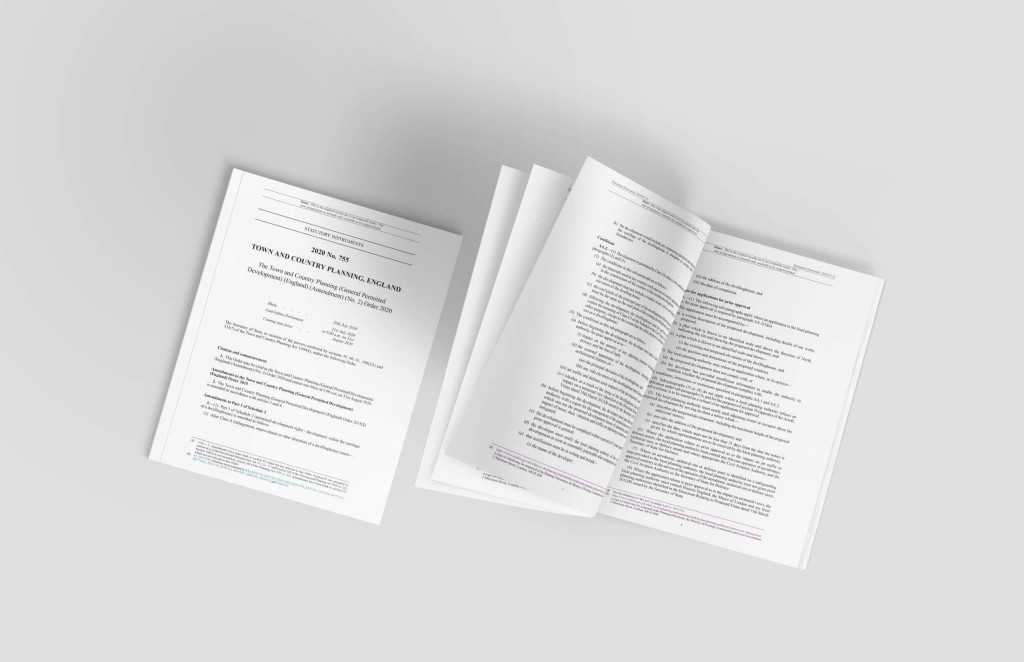

The underlying debate around controversial permitted development rights is similar to the one around space standards: to what extent should housing delivery be regulated, and to what extent should it be left to the market?

In 2020, then-Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government Robert Jenrick intervened with a clear answer: even permitted development applications should be subject to national space requirements.

For homes created through permitted development, such as converting offices into homes, nationally described space standards are now always mandatory in full, with no wiggle room. This means that a new one-bed flat with a shower room, created under permitted development, is subject to the 37 sqm requirement.

The requirement was set in response to widespread criticism of the substandard housing stock created by office-to-residential conversions under permitted development rights.

The disturbing fact is that the UK is commonly cited to have the smallest average home size compared across countries in Europe. Furthermore, in 2011, homes sold by the eight largest housebuilders in the UK were on average 8 square metres smaller than the new minimum space standards implemented by the GLA.

Tacked onto the extreme examples passed through the planning system under permitted development, mounting concerns over home size demonstrate a need for some kind of standard to guide the delivery of better quality housing.

As we said earlier, it was already understood back in Victorian England that living space and life quality are intertwined. Today, that link is even more well documented, especially when it comes to residents’ mental health as well as the strength of their household and community relationships.

In the London Plan, the adoption of the national space standard is explained from the perspective of strategic sustainable development. The cumulative effect of poor quality homes across the city has both social and economic implications, and the space standard seeks to address that.

Some have argued that space standards contribute to the housing crisis by placing constraints on supply. However, the impact of permitted development rights on the housing landscape has suggested that it’s insufficient to think about the crisis in terms of delivery numbers alone.

Recent analysis by the Local Government Association revealed that a whopping 18,000 affordable homes were lost through permitted development since 2015. Moreover, the Town and Country Planning Association has exposed the implications of substandard, windowless units on wider placemaking efforts.

When considering the impact of space standards on the larger housing crisis, then, they can also be seen as a necessary quality control that contributes to the cultivation of well-designed places.

Of course, buildable land within London and other cities across the UK is increasingly scarce. Small sites offer a way forward, but present the challenge of delivering housing that meets the minimum requirements.

Here are a few examples of constrained sites that we’ve devised a way forward on.

In this case, we started with an urban vacant lot. Like many spare pieces of land in big cities, it didn’t come in a neat, classically symmetrical shape. Instead, it was a lop-sided wedge. Nor was it a question of simply seeing how many units we could fit in - the council (understandably) insist on a range of flat sizes and also wanted the homes to be dual aspect.

That meant that we were working with an awkward shape and a lot of demands we had to meet. Meet them we did, though: we designed two one-bed flats, five two-beds and one three-beds. All comfortably exceeded space standards for flat sizes. Each of them has its own private balcony, meeting some of the outdoor space requirement, with the rest being met by the large shared roof terrace.

This showed that an irregular plot doesn’t mean that you can both meet space standards and create a good number of much-needed homes.

In this project, we designed a flat conversion in a conservation area, the client wished to convert a family home into three flats, which required us to check with the council’s minimum-size requirements for the original house to make sure our proposal was in the clear.

We accomplished this flat conversion through an extension in order to maximise the value of the site and exceed the London Plan space standards, in order to deliver the livable space that our client required.

In this case, we replaced a two-flat block with a four-flat block. This required us to ensure that we were meeting the London Plan requirements for each configuration.

Interestingly, the existing flats on site did not actually meet the space requirements, so our proposal increased the development’s quality by bringing it up to standard.

We extended this principle of good design into every facet of the proposal, maximising the site’s performance by improving its housing offerings.

In June 2023, the Mayor of London published Housing Design Standards, a London Plan Guidance document. Along with many pieces of guidance aimed at dramatically raising the bar for housing in the capital, the LPG also contains a table of best practice space standards.

These don't replace the national standards - rather, they are what developers in London should be aiming to achieve. The improvements that the London government is hoping to encourage are more storage and better working-from-home space.

| Type of dwelling | Minimum gross internal floor areas (GIA)* and storage (sqm) |

Best practice extra space

|

||||||||

| Number of bedrooms | Number of bedspaces | 1-storey dwellings | 2-storey dwellings | 3-storey dwellings | Built-in storage | |||||

|

1b

|

1p | 39/37 | 43/41* | 1 | 1.5 | +4 | ||||

| 2p | 50 | 55 | 58 | 63 | 1.5 | 2 | +5 | |||

|

2b

|

3p | 61 | 67 | 70 | 76 |

2

|

2.5

|

+6 | ||

| 4p | 70 | 77 | 79 | 86 | +7 | |||||

|

3b

|

4p | 74 | 84 | 84 | 94 | 90 | 100 |

2.5

|

3

|

+10 |

| 5p | 86 | 97 | 93 | 104 | 99 | 110 | +11 | |||

| 6p | 95 | 107 | 102 | 114 | 108 | 120 | +12 | |||

|

4b

|

5p | 90 | 101 | 97 | 108 | 103 | 114 |

3

|

3.5

|

+11 |

| 6p | 99 | 111 | 106 | 118 | 112 | 124 | +12 | |||

| 7p | 108 | 121 | 115 | 128 | 121 | 134 | +13 | |||

| 8p | 117 | 131 | 124 | 138 | 130 | 144 | +14 | |||

|

5b

|

6p | 103 | 115 | 110 | 122 | 116 | 128 |

3.5

|

4

|

+12 |

| 7p | 112 | 125 | 119 | 132 | 125 | 138 | +13 | |||

| 8p | 121 | 135 | 128 | 142 | 134 | 148 | +14 | |||

|

6b

|

7p | 116 | 129 | 123 | 136 | 129 | 142 |

4

|

4.5

|

+13 |

| 8p | 125 | 139 | 132 | 146 | 138 | 152 | +14 | |||

The best practice home sizes are generally around 10-14% larger than the national minimums: so for example 41 sqm instead of 37 sqm for a 1-bedroom, 1-person flat with a shower, 77 sqm instead of 70 sqm for a 2-bedroom, 4-person flat, and 114 sqm instead of 102 sqm for a 2-storey, 3-bedroom, 6-person house.

In addition, the best practice for ground-floor flats is 3.5m floor-to-ceiling as opposed to the London Plan 2.5m.

Altogether, this represents quite a substantial difference. What needs to be seen is how London councils will mention failure to meet best practice sizes when refusing planning applications. We will keep you updated in the months to come.

Regardless of your project goals, we are committed to applying our understanding of the required – and desired – space standards to the task at hand, in order to ensure that you’ll have the best likelihood of success with the council.

It’s part of the ethos that we apply to every project, as planning policy requirements directly inform our approach to good design.

Robin Callister BA(Hons), Dip.Arch, MA, ARB, RIBA is our Creative Director and Senior Architect, guiding the architectural team with the insight and expertise gained from over 20 years of experience. Every architectural project at our practice is overseen by Robin, ensuring you’re in the safest of hands.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message