Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Are you ready to lead the way in transforming urban housing?

As property developers, you have a unique opportunity to redefine city living with co-living spaces, a rapidly growing trend in England's cities.

With cities facing increasing populations and limited affordable housing, co-living isn't just an option—it's a necessity. It's a chance to create housing that's not only profitable but also meets the needs of today's society.

But the journey from idea to a thriving co-living community comes with its own set of challenges and opportunities.

Designing and building a co-living space requires more than standard property development. It demands attention to detail, an understanding of communal living, and a vision to create spaces that are more than just a place to live. They need to be vibrant, functional communities.

In this article, we'll be your guide to co-living development in England. We'll explore why co-living is on the rise in major cities, how it differs from traditional housing like HMOs, apart-hotels, and student halls, and we'll delve into the essential aspects of planning permission and design that make a co-living space successful.

Whether you're embarking on your first co-living project or looking to refine your existing development strategies, this guide is a valuable resource to understand and navigate co-living development in England's bustling cities.

Now, let's begin.

Co-living, also known as large-scale shared living schemes, is a form of accommodation providing completely private rooms and bathrooms, with shared kitchens and living facilities. These facilities are expected to be always available for cooking, dining, relaxing and socialising for the residents and their guests.

The best way to discuss what a co-living space is would be to define what it is not. A co-living space is not a flatshare, not a hotel and not student accommodation. It is a type of accommodation completely unique to itself.

For single-person households, co-living provides an alternative option to HMOs and self-contained flats. It is a style of living that allows for sufficient individual space, and opportunities to socialise with your community.

Officially, the London Plan defines co-living as:

“Large-scale purpose-built shared living developments are generally of at least 50 units. This type of accommodation is seen as providing an alternative to traditional flat shares and includes additional services and facilities, such as room cleaning, bed linen, an on-site gym and concierge service. Tenancies should be for a minimum of three months to ensure large-scale purpose-built shared living developments do not effectively operate as a hostel.” (The London Plan 2021, p.212)

In 2021, The London Plan introduced ‘Policy H16: Large-scale purpose-built shared living’, which aimed to accommodate ‘new’ ways of living. It set out many different requirements for a co-living development, including design quality, operation under single management, spatial size requirements, minimum provisions for communal amenities, a management plan, affordable housing provision and more.

While Policy H16 was generally well received, there was concern from developers regarding the rigidity of some details. Fortunately for those developers, two years later, in February 2024, the ‘Large-scale purpose-built shared living, London Plan Guidance’ was published, addressing some of these perceived issues.

This fresh guidance provides more detailed advice on how developers and planners should implement Policy H16, aiming to set clear standards for communal areas, kitchen facilities, and outdoor spaces, while also allowing for flexibility in design to promote high-quality living environments.

Let’s take a closer look.

As mentioned above, a planning guidance was published in February 2024 which made changes around space requirements, accessibility standards, and the location of co-living properties, among other updates. It added specificity, providing more legible guidance for those pursuing this style of development.

In a nutshell, the changes are as follows:

As you would expect, the co-living space standard is designed to make sure residents aren’t cramped, enabling a comfortable and safe existence. This is, of course, particularly important in properties like shared living homes that have far more residents than your typical family home.

However, there is a fine balance between ensuring there is enough space for an individual or a couple, while not providing so much space that a whole family is squeezing themselves into sub-par self-contained accommodation.

Interestingly, instead of these space requirements being mandated, they are now a benchmark to aspire to, granting developers more freedom in their designs depending on the scope of the project.

On this note, page 6 of the guidance reads, “Some flexibility in the assessment of LSPBSL applications against these recommended benchmarks may be applied to the design, scale and provision of these facilities in consideration of the site’s location and context, or other scheme-specific factors where it is demonstrated that qualitatively good design outcomes are being achieved.”

This means planning departments won’t necessarily dismiss a project if these benchmarks aren’t met, and instead will be able to apply their own judgement based on the context of the development.

With this in mind, let’s take a look at these benchmarks when it comes to space, as well as what is required for kitchen, dining, and laundry facilities.

Standard private unit size |

18 - 27 sqm (unchanged) |

Accessible private unit size |

28 - 37 sqm (unchanged) |

Internal communal amenity size |

Minimum of 4 sqm of internal communal facilities per resident (up to 100 residents). For every additional resident from 101 to 400 there needs to be 3 sqm per additional resident, and for every additional resident from 401 there needs to be 2 sqm per additional resident. |

External communal amenity space |

For up to 400 residents there should be a minimum of 1 sqm per resident, then for every additional resident from 401 there should be an additional 0.5 sqm. |

Kitchen |

Minimum 0.5 sqm per resident, to include one cooking station per 15 residents |

Dining |

Two dining spaces per cooking station; or number of dining spaces = 15% of total residents |

Laundry |

One washer and one dryer per 35 residents |

According to the new guidance, communal areas should be well-ventilated, conveniently accessed, and designed for flexible use to foster a sense of community among residents. A key principle of shared living accommodation is to promote a feeling of belonging and connection with fellow residents, so ensuring there are adequate communal spaces is a natural part of facilitating that.

There is also a new emphasis on inclusive design to ensure communal areas meet the needs of diverse populations, promoting a balance between privacy and community.

The guidance also addresses concerns about over-concentration of co-living developments in certain areas, ensuring that such projects do not negatively impact housing diversity or the wider community. It suggests that co-living schemes should integrate well with existing neighbourhoods and contribute positively to local growth.

In typical UK planning system fashion, each council has its own interpretation and adaptation of regional and national policies.

The London Plan must be followed by every planning authority within Greater London; however, they are free to add additional requirements to those in the London Plan. Below are a few examples of how different councils have adopted Policy H16 into their local plans.

If you don’t see your council below, it is important to conduct additional research into what may be required of your co-living development, here are some select examples of how Policy H16 is reflected in local plans.

If your local plan does not include any information about co-living spaces, it is best to refer back to the London Plan as your one guide to development, and advisable to take your scheme to pre-application to better understand your council’s stance on co-living spaces.

Westminster’s City Plan, finalised in 2019, shows support for the development of co-living schemes, suggesting that they offer young professionals an acceptable form of accommodation.

They suggest that it can be particularly advantageous for young professionals when the communal space offers various live/work amenities. The council “welcome[s] innovative ways to deliver more housing and address the high cost of traditional self-contained market housing” (City Plan, p.65).

Hackney’s local plan 2020-2033 shares similar principles as Policy H16, but adds a further restriction to proposed co-living developments, including that development is only appropriate when the site has been deemed unsuitable for conventional self-contained accommodation. It also requires the provision of at least 10% adaptable wheelchair-accessible units.

Traditional homes are still the council’s priority, however, Hackney recognises the value of co-living spaces where standard residential accommodation is not suitable.

Southwark council echoes the policies set in Policy H16. Similar to The London Plan, the council stipulates an affordable housing contribution of at least 35% of accommodation or cash payment when housing cannot be provided on-site. It does so to offset an unrestricted spread of co-living spaces.

Lambeth’s Policy H13 addresses their council-specific requirements for co-living developments. Their policy builds upon the foundation set by London Plan Policy H16.

Tower Hamlets’ supporting text for Policy D.H7 discusses “a recent growth in London of purpose-built, large-scale, higher quality HMOs charging commercial market rents. This includes, for example, accommodation modelled on student housing but available for a wider range of occupants or accommodation described as ‘co-living’.”

It’s interesting that Tower Hamlets continue to view this as a subset of HMOs, rather than - as the London Plan seems to suggest - an entirely separate type of residence.

Given the newness of co-living in the UK, the majority of developments are within London; however, their growing popularity is inspiring other large cities, such as Manchester or Birmingham, to consider such schemes.

Where the boroughs within Greater London must abide by Policy H16, those councils outside the capital are free to regulate co-living planning as they please.

Like some councils in London, various councils across the country have yet to incorporate co-living in their local plans, and others have extensive policy documents for their regulation.

For example, the Birmingham city council published a supplementary planning document solely on large-scale purpose-built shared living schemes. The council details the definition of co-living, the sui generis co-living class, necessary features and facilities, extensive application considerations, spatial requirements and planning policy relevance.

As the concept of co-living gains popularity, we can expect to see detailed planning documents, similar to that of Birmingham city council, being developed by large and medium-sized cities across the UK.

We have seen that a co-living space is a building with 50 or more rooms, all sharing communal dining and living facilities.

You may be thinking this sounds very similar to a very large HMO (house in multiple occupation), and many argue that they are the same thing. So is it a popular misconception that co-living spaces are simply bigger, up-market, fancier versions of HMOs?

Sure, on the surface it seems like they like to fulfil the same function. And how different can a communal kitchen and living room with private bedrooms be?

However, co-living spaces are expected to offer more than the typical HMO. This is clearly demonstrated in the Policy H16 requirement for a management plan agreement before planning permission is granted.

Of course, entering the market as a co-living space is a great way for upscale developers to avoid the (misplaced) stigma associated with HMOs, but you will be expected to provide more services than in a traditional HMO.

Co-living spaces are expected to go beyond the established HMO-style living experience with a focus on design, sustainability and community. We will explore some of the services that are expected of co-living spaces later.

So it seems like it is possible to distinguish a co-living space from an HMO, but it does sound very similar to an apart hotel, a set of apartments that offer short-term accommodation and hotel services.

A key difference is a goal of co-living to foster community.

The London Plan defines an apart-hotel as

“Self-contained hotel accommodation (C1 use class) that provides for short-term occupancy purchased at a nightly rate with no deposit against damages”

Most councils, and Policy H16 of the London Plan, require minimum stays of three months in any co-living space. It is not the goal of co-living spaces to operate as upscale hostels or business travel accommodation. Requiring a minimum stay is a key differentiation from apart-hotels. Residents have the opportunity to meet and connect with their building community - rather than meeting like passing ships in the night as they would in hotels.

All buildings and land in this country fall into one (or more) use classes. The idea is that if you want to change that use, you will need planning permission - although in some cases, you can use permitted development instead.

Most types of accommodation fit into the C class: C1 is hotels (and, as mentioned above, apart-hotels, at least according to many authorities, including the Mayor of London). C2 is residential institutions, C3 is your standard flats and houses and C4 is small HMOs. Large HMOs are not in class C - they are in their own use class (or, in planning terminology, sui generis). Many councils treat student accommodation as sui generis, too, although some student flat developments have been considered as C3.

The London Plan makes it clear that Policy H16 is for “sui generis non-self-contained market housing.”

There are a couple of consequences of that. The first is that turning a building into or from shared living will always need full planning permission. The second is as these are the not individual flats that you would expect if they were labelled C3, the national space standards (under which the smallest possible unit is 37 sqm - as opposed to Policy H16’s 18 sqm) do not apply.

As someone who may have a vested interest in the development of a new co-living space, you are probably asking if H16 can be used to justify conversions. Yes, it can!

Now that co-living spaces have been entered into policy, adherence to those policies is a material consideration in the planning application. If you are considering an application for co-living space planning permission, you will need to demonstrate that your schemes will promote an inclusive and diverse contribution to the neighbourhood.

The London Plan asks boroughs to seek large-scale purpose-built shared living schemes that will contribute towards the creation of mixed and inclusive communities. Demonstrating your scheme’s ability to fulfil this can be leveraged to your council.

To increase the likelihood of gaining planning permission for your co-living scheme, you need to convince the council that a development of this type will be both suitable and advantageous for its surroundings.

If you are a developer trying to get past the stigma (however undeserved it may be) that HMOs have acquired, I can imagine you are wondering whether H16 can be used with proposals of fewer than 50 units.

Yes, you can! While the London Plan defines co-living schemes as developments with generally 50 or more units, it is not a requirement. Importantly, submitting an application referencing Policy H16 for a co-living space will require extra details and resources than submitting an application for a large HMO.

Be prepared to meet size requirements for different rooms and communal areas, and to provide an in-depth management plan. When creating an H16 co-living space, you will be expected to offer additional services that would not need to be supplied to your HMO, such as a concierge service and room cleaning.

Developing and operating a co-living space is a large undertaking, if it is only rooms and basic facilities you are looking to provide, it is better to stick with an HMO. But, if you are ready to take your property to the next level, H16 is your guide there.

You have learned that co-living spaces are not just buildings of 50 or more flats, they share kitchen and living spaces. You also have learned that they are not HMOs. By this we mean to say, co-living spaces are more than just big houses rented to unrelated people.

When operating your co-living space you’re expected to provide more than just a kitchen and living space - even though that is what we just said sets co-living spaces apart from flats. The examples of currently offered co-living schemes will demonstrate the requirement for social and lifestyle offerings.

This co-living space, located in Bermondsey, London, is a clear example of the services expected of your new development.

Not only does this scheme provide luxury communal spaces - their programme offers activities such as monthly house dinners, guest speakers and expert-led workshops, quarterly full-house parties, catered breakfasts and a holistic mind/body wellness programme.

This scheme is a demonstration of the expectations derived from the co-living reputation. In its recent growth, co-living has earned the reputation of accommodation for young, wealthy, urban professionals. Or as this scheme proudly proclaims, “a cross between a large, chic shared house, a private members club and a wellness retreat.”

This co-living company, with UK locations in Old Oak and Canary Wharf, advertises an all-inclusive bill that includes gym access, regular cleaning and linen change, a golf simulator, swimming pool, sauna, cinema and cultural events programme.

As we said, a co-living space is much more than just an extremely large house.

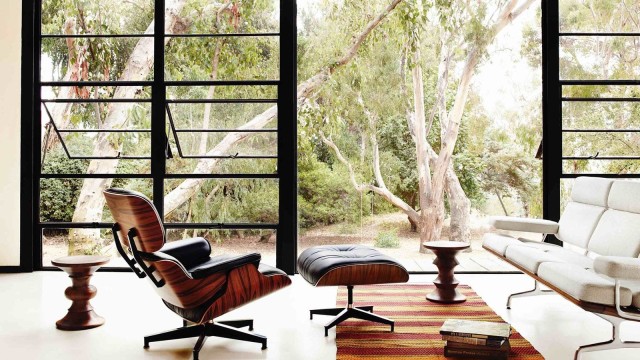

Urbanist Architecture has worked on the initial stages of what will be - when completed - an extremely ambitious and very high-end office to shared living conversion. We were engaged to carry out a comprehensive appraisal of its planning prospects and a full architectural feasibility study with conceptual design solutions to understand how vast open-plan office spaces can be transformed into stylish and inviting places to live.

Conscious of the requirements of Policy H16, we knew that getting the shared living areas right was every bit as important as the bedrooms. We’ve stressed throughout this article that the intention behind the policy is that these should be communities, they exist for people who genuinely want to spend time with their fellow residents.

With that in mind, we designed chic places to eat, cosy niches for private conversations, a cinema room, a pool room and a gym. All aimed at providing not just comfort and convenience, but the kind of shared experiences that help to build friendships.

As we are a firm that really appreciates the chance to work on interiors as well as priding ourselves on our planning expertise, this very much played to our strengths.

We also are currently working on two apart-hotel projects, one in London and one on the south coast, which means we have become very aware of the planning and practical differences between these two fast-growing contemporary types of accommodation.

Urbanist Architecture is a London-based RIBA chartered architecture and planning practice. With a dedicated focus in proven design and planning strategies, and expertise in residential extensions, conversions and new build homes, we help landowners and developers achieve ROI-focused results.

If you're seeking a multidisciplinary team of London architects specialising in crafting thoughtful and practical design solutions tailored for co-living spaces, we are the perfect fit.

Our approach involves a meticulous preparation process tailored to co-living concepts, addressing both architectural and interior design requirements. We also provide expert guidance in securing planning permissions, ensuring that your co-living vision can be seamlessly transformed into a tangible reality.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message