Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

When it comes to a new home in the Green Belt, most people seem to imagine a house on what had been an empty field or a clearing in the woods. But one-off houses like that are rare and special (and almost always extremely expensive).

If you want to build a home to match your own vision in the Green Belt, the most practical way to do this is to find a home that’s already there and either fully or partially demolish it and put your replacement dwelling in its place.

In this article, we explain the rules governing replacement homes in the Green Belt, and run through some of the key questions to consider if you are planning to build one of these houses.

In broad terms, a replacement dwelling is either an entirely new structure or an extensive reconfiguration of an existing structure. It’s likely to adhere to the previous building footprint or present a moderate increase in size, justified on the basis that what’s being proposed will not constitute greater harm to the openness of the Green Belt than what is already there.

The rationale behind a ‘replacement dwelling’ has a lot to do with the purpose of Green Belt protection in the first place. Among other things, Green Belt policy is meant to restrict sprawl in order to preserve the openness of the countryside.

As such, a replacement dwelling keeps building where it already is, rather than extending out further into undeveloped land. Therefore, our experience has taught us that it strengthens proposals for replacement dwellings if they embody other aims of Green Belt policy.

For instance, design should be appropriately set within the landscape and well informed by its surroundings. We’ll also discuss sustainability in this article, along with the ways in which green building technologies can help support the case for a replacement dwelling.

First, we’ll start by saying that the overall idea behind your proposal should be that it offers a material improvement to the structure that already exists. This improvement should be comprehensive: it should promote higher design standards, offer more substantial environmental contributions and make better use of the specific qualities of the site that the applicant needs to enhance their quality of life.

As we’ll later explain in further detail, the definition of a ‘replacement dwelling’ comes from Paragraph 149 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). While Green Belt policy strongly protects all land under its designation, Paragraph 149 lists a few key exceptions that provide routes to limited development opportunities.

One of these is the replacement of a building of the same use – and of a relatively similar size. This article will explore the policy’s precise wording and expose its ambiguity.

For now, the important point is that national policy only provides a basis for understanding what a replacement dwelling can be: it does not lay out any specific guidelines on design or otherwise define a range of metrics that determine appropriate building size. To understand what a replacement dwelling can be, we, therefore, have to look to local councils in the Green Belt, because they are the ones actually tasked with interpreting the policy.

This means that, even though national policy sets the stage for Green Belt governance, the true definition of an acceptable ‘replacement dwelling’ will differ from council to council. Local planning precedent, in addition to policy, is therefore what helps us determine what is generally permissible – and where we might be able to push boundaries.

In order to understand exactly what the policy exception allows for, we’ll now take a look at its wording, and some examples of how the ‘replacement dwelling’ idea has played out in practice.

One key thing about planning in the Green Belt is that, unlike most other types of development, the main policies are set at national rather than local level. Councils can have their own Green Belt policies, but these are not allowed to clash with the NPPF in any way.

That means that the essential questions are determined by national policies but – as we will see – some important details, especially to do with the maximum size of your new home or homes, will be assessed under local rules.

So what does the NPPF say about replacement dwellings?

Paragraph 149 lists the exceptions to the rule that “construction of new buildings” in the Green Belt is “inappropriate”. These include:

“d) the replacement of a building, provided the new building is in the same use and not materially larger than the one it replaces;”

And:

“g) [...] the partial or complete redevelopment of previously developed land, whether redundant or in continuing use (excluding temporary buildings), which would: ‒ not have a greater impact on the openness of the Green Belt than the existing development”

It’s worth taking a moment to discuss the difference between these two in theory and in practice.

Subparagraph d) is the one thought of by planners as the “replacement dwelling” clause, although it isn’t specifically about homes. It offers a one-to-one swap between “a building” and “a new building”.

In typically vague wording, the NPPF instructs that the replacement can not be “materially larger” than the existing house. We’ll explore how local planning authorities interpret that below.

There are even more grey areas with g), where an unspecified number of buildings in unspecified uses can be replaced by an unspecified number of buildings in unspecified uses as long as they don’t have “a greater impact on the openness of the Green Belt than the existing development”.

An obvious problem here is that the “openness of the Green Belt” is a slippery concept. It has been the subject of many court cases, without us getting any closer to something everyone involved professionally agrees on, let alone something the ordinary citizen can be expected to get their head around.

The one thing that is important to know is that “previously developed land” (PDL) does not include “land that is or was last occupied by agricultural or forestry buildings” – so a barn does not count while, for example, a stable does.

The reason we think it is useful for you to know about g) as well as d) is that it opens up the possibility of you replacing one house with two, for instance.

Let’s get back to that fuzzy phrase “materially larger”. Some councils treat this on a case-by-case basis, others have clear ratios. The more generous councils go with a 20/30 rule – you can increase the footprint of the house by 20% and the volume by 30%.

It’s vital that you and your architects are certain about your council’s approach to this before you begin to consider submitting anything to them. You need to check both their policies and how they have handled recent applications.

On the one hand, you don’t want to annoy them by asking for far more than they would ever consider. On the other, you might find you’ve been incredibly cautious – it could turn out that you are dealing with a 20/30 council and that you’ve ended up with a much smaller house than was necessary.

We should also say that there has been at least one recent appeal where the Planning Inspector overruled by the council and allowed a substantially larger house than the council was willing to accept. The logic the Inspector used was that when seen within the landscape, the new house would look fitting and in proportion and so the council’s approach was too rigid and arbitrary.

The lesson from that is if you are willing to take a risk and have the time to go to planning appeal, you could end up with a noticeably larger replacement house. There are no guarantees, but there can be rewards for those who have the resources to play the long game.

As we mentioned, clause d) talks about replacing a building (singular) with another building (singular). In practice, however, applications in the Green Belt are very often concerned with the total sum of structures on the plot.

People who want to build usually want to get the most space they can, and councils sometimes like the idea of a much tidier space – here’s Elmbridge Borough Council’s PDL policy:

“Applicants are encouraged to take the opportunity to make improvements to the openness of the Green Belt where possible, which could include[...] removing a sprawl of buildings in favour of a single, cohesive development that leaves the remainder of the site open.”

It’s great then if you are in a position to offer to demolish old sheds and garages and add that space to your new house. But first, you need to check whether they count as previously developed land. They don’t fit into that category if they are: a) for agricultural or forestry use or b) temporary (which, in this case, is largely defined by buildings that can easily be moved and that aren’t built into the foundations. So you might have a static caravan that has been there for 20 years, but the council could argue that it is not a permanent structure).

And before you include all your outbuildings in the list of what you are prepared to demolish, have a think about whether you might need future versions of these structures.

When granting planning permission in the Green Belt, councils sometimes remove permitted development rights for the new house. That leaves the humble garden shed you want as a whole new building in the Green Belt, something it is incredibly difficult to get planning permission for… So do factor in any outbuildings you might one day need when doing your calculations.

In most cases, the local planning authorities would like to see the replacement dwelling built on the footprints of the previous/existing dwelling. However, this may be impossible in practice for reasons related to the context of the site.

The considerations may include:

Therefore, the local planning authorities may consider your replacement dwelling to be positioned at an alternative location at your development site.

Sometimes when you find replacement plots for sale in the Green Belt, you’ll notice that there isn’t an intact house on the site. Rather, you will be told that there used to be a home there.

Does that count?

Answer: sometimes.

The National Planning Policy Framework says that land is no longer considered as previously developed if “the remains of the permanent structure or fixed surface structure have blended into the landscape.”

There are certainly examples of planning granted on the basis of a structure that is no longer there. This is particularly likely if planning permission for a replacement building was granted, the existing one demolished and then, for some reason, the new one was never built.

But the fact is that you are generally on much safer ground if the building you want to replace is still there.

Let’s return to the question of how big your new house or houses can be. We talked about the increase in volume, but held off on an important question: does the unspecified, 10% or 30% maximum increase in volume allowed include the whole house or just the house at ground level and above?

Or to put it another way, is a basement a free extra?

This is a question for which national policy offers no answers. Local planning authorities take differing attitudes: for some, the total amount of development in the Green Belt is what matters.

For others, what happens below ground has no effect on openness. And some – maybe the majority – are relaxed about basements but not about the lightwells or sunken courtyards that you’ll need if you are planning to have bedrooms on your lower floor.

So how the council views basements in the Green Belt is another one of the points at which you – or the team you hire – will need to take a thorough look.

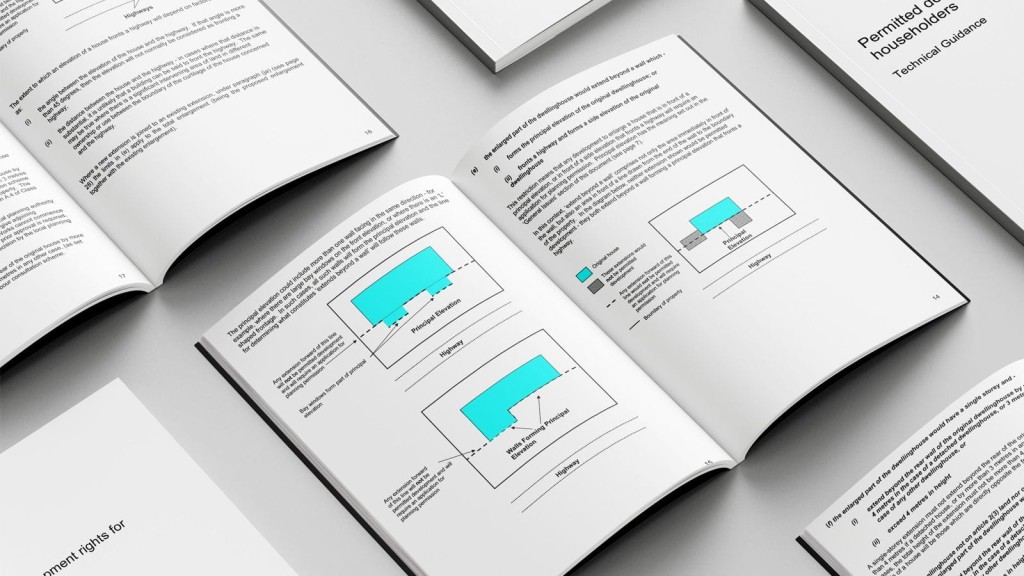

Here’s a fact that sometimes surprises people: permitted development rights are exactly the same in the Green Belt as they are in unprotected parts of England – unless your area is covered by an additional designation (conservation area, area of outstanding natural beauty, national park, etc).

That means that if you haven’t already used your permitted development rights, you are allowed to increase the size of your existing house or add garden outbuildings.

Using permitted development rights is often a fallback option mentioned in Green Belt applications: essentially, you are saying to the council that if it does not allow you to build the well-designed new home you are asking for, what everyone will end up with is the current house now with sprawling extensions tacked on or large outbuildings.

The crucial point about fallback options is that they shouldn’t be an idle threat: if planning officers don’t believe you have any intention of building those extensions or outbuildings, they will simply ignore your fallback option. It always needs to sound like something that it would be worth your while to do.

There are some very large homes out there. That’s why, when it comes to replacing a property in the Green Belt, people can think, “Why just one house? Why not two or three?”

Sometimes the aim is to make money, other times the idea is to provide neighbouring but separate homes for different generations of the same family.

Either way, you might start with some simple sums. If the current house is 400 sqm (4,300 sqft), then each of the new homes can be at least 200 sqm, and that will be fine, right?

Not so fast.

Firstly, as we said earlier, the replacement dwelling clause allows for a one-to-one replacement. So we’ve shifted to the previously developed land option, where you need to think about the impact on the openness of the Green Belt. And the equation is now very different, because the council has the option of considering much more than the size of the buildings.

Instead, they will look at the full impact of one or more additional households. With an extra family, there will be the stuff of life surrounding the house: cars, bins, garden furniture, washing lines, kids’ toys… You may be surprised to learn that local planning authorities can take all of that into account when looking at a Green Belt application, but they can.

Plus, the logic that applies in the rest of the country still applies in the Green Belt: what’s the effect on traffic?

Are the schools and shops near enough?

And so on… None of this is a problem for a single replacement, but can be if you are replacing one home with two or more.

We know of a pair of applications for buildings of exactly the same dimensions and exterior design on the same plot in the Green Belt: the one that wasn’t for a home was allowed, the one that was for a home wasn’t, all because of the effect of a new household.

Simply put, things get much more complicated with multiple homes. But that doesn’t mean you should rule out that option.

What’s the reason you want to build a replacement house?

Since we know it can’t be that much bigger than the existing one, it’s normally either to substitute a poorly designed house with one that makes better use of light and space or to create something that meets your vision of your ideal home. You might want to place it on a different part of your plot.

All of these point to a clean slate, so what we are going to say next might sound contradictory, but here goes: if you can, we advise you to incorporate some of the existing house into the new one.

Why?

The main purpose is to limit the greenhouse gas emissions caused by demolishing and rebuilding. While making a house more sustainable alone will not get you planning permission in the Green Belt, it is an important element of securing consent for a replacement dwelling in the countryside.

The secondary reason is to reassure the council that what you are proposing is rooted – that even if you are suggesting a radical new design, it has some connection with what was there before.

Thanks to what we could call the Grand Design effect, there’s an expectation that new homes in the countryside will be daring and different.

On the other hand, many councils and local communities in rural and semi-rural areas have an attachment to traditional styles of architecture.

It’s often easier to get planning permission if you create something that at least on the outside looks like it has been there for 150 years already.

What you do inside the house, of course, is completely different – you can take a fully contemporary approach inside a cottage or barn-style exterior. That’s not always ideal – we applaud councils that take a more open-minded approach to what they allow – but it can be the pragmatic one.

Whether you go for traditional or contemporary, your design should always feel like it belongs on that plot and fits in well with its surroundings.

Remember when we said the house you’re replacing doesn’t always have to be physically there? Well, this is one of those cases.

The original derelict house had been demolished over a decade before we were hired, but the works to build the new house had begun, so an old planning permission was still in place.

We were hired as planning consultants for this project - although we generally provide combined architectural and planning services, we can also be hired for just one of these tasks.

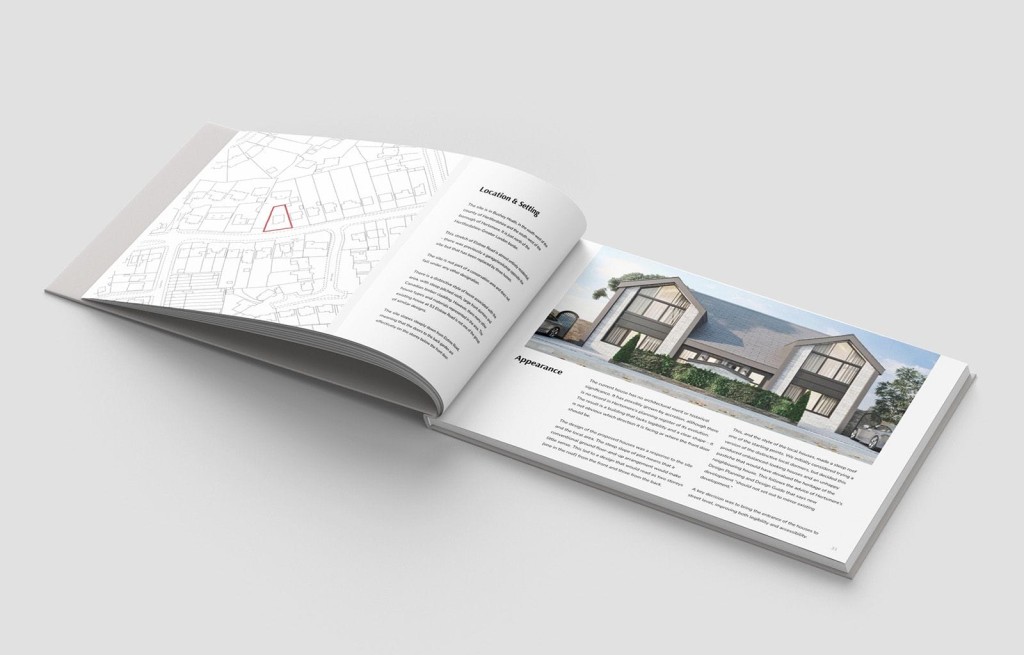

The architect had created a modern design – with large windows letting in plenty of light – that, however, has a shape and timber cladding that evoke traditional barns.

A swimming pool was incorporated into the planning application so that it did not become one of those later additions that can become tricky to get consent for. The design was highly sustainable, including solar PV panels, a heat pump and energy-efficient building materials.

Our task was to use a very thorough Design and Access Statement to help convince the council that this large house would sit conformably within the landscape, and the sustainability measures would mean that a home on this scale would be acceptable. The council was persuaded and granted permission for this very big house in the country.

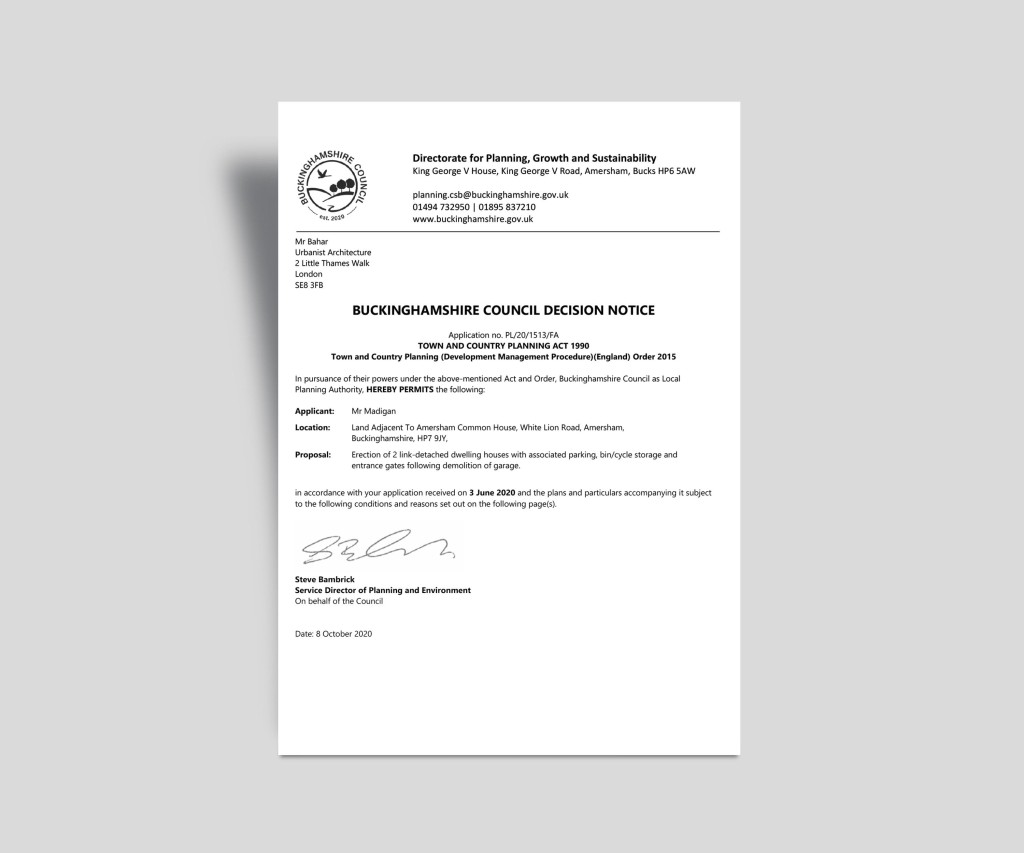

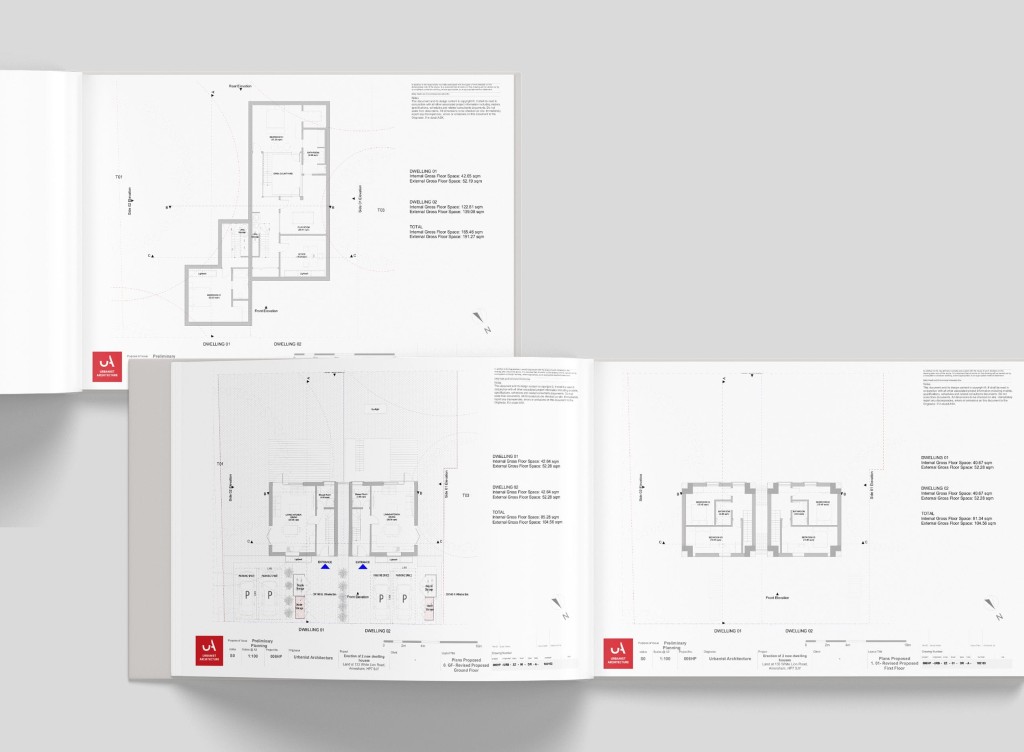

This one started with a large garage. It was big enough that it could have been converted into a couple of homes – that was the fallback position.

The council actually considered three different Green Belt exceptions when looking at the application: d) and g), which we’ve already talked about, and e), which allows for limited infilling in villages. In the end, the planning department felt that g), previously developed land, was the correct one.

We took the design through two rounds of pre-application meetings with the council. Our first version had three traditional-looking houses. The council was clear that three was too many.

We came back with two homes, now in a much more contemporary style and to our mind, attractive design. The council still argued that they were too big, but we countered that much of the 37% increase in volume came from the basements. In the end, the council accepted that was reasonable.

Even though this was a reuse of previously developed land, we were careful to design around existing trees. The ecological report suggested which native species of plants would encourage local wildlife to thrive, so we incorporated those into our landscaping plan.

That level of attention to detail helped us get planning permission. To learn more about this case study, please follow this link.

As we’ve demonstrated, the rationale behind a replacement dwelling is complex. It has to respond equally to the aims of national policy and to the site-specific context that will be of concern to the local council.

Some local councils in the Green Belt have produced guidance on replacement dwellings in response to concerns that these applications are adversely impacting the character of certain areas. One such council is Cheshire East, which has specific requirements for planning applications for replacement dwellings (we’ll touch on these in a bit).

Given the intricate nature of planning applications for replacement dwellings, it’s therefore important that a strong submission package goes behind the minimum requirements. A successful application has to tell a story, presenting a well-researched planning argument that is clearly informed by the relevant local precedents. It also needs to be attentive to any advice produced by consultancy reports.

At Urbanist Architecture, we advise our clients on the appointment of specialist consultants who can examine the necessary ecology, heritage and transportation concerns on-site in order to demonstrate that material planning considerations have guided the design strategy.

These supporting documents will accompany the key components of your application package: A full set of drawings, and a substantial Design and Access Statement. Let’s dive into our philosophy on these further.

First, a full drawing set should include existing and proposed architectural drawings that demonstrate a high quality of design.

Given some councils’ concern about the impact of replacement dwellings on local character, it should be clear that the design, however contemporary, has responded to site-specific qualities - such as its topography or history.

A sensitive design is particularly important in the case of replacement dwellings on sites that contain listed buildings or are otherwise in conservation areas. Specific guidance varies from council to council, but it will likely be important to protect the fabric of these buildings - especially if the relevant heritage listings identify internal features.

We recently worked on a design proposal for a replacement dwelling in London, where Metropolitan Open Land is given the same policy protections as the Green Belt. We, therefore, approached our design strategy as equivalent to that for the Green Belt.

The site was not in a conservation area, but it sat between two heritage assets: one Grade II-listed building and another locally listed building. It also fell within an archaeological priority area, which required us to appoint specialist heritage and archaeological surveys.

Given all of these forces, we were left with a very specific design decision to make – whether to take a pointedly contemporary approach, bringing the site’s history into modern use, or whether to pursue a more conservative, traditional design that could have veered toward the pastiche.

We opted for the former while crafting other ways to reference the character of the area. Keeping to the historic building footprint and development pattern along the road, for instance, allowed us to formulate a design strategy that responded to the urban grain and local streetscape.

Our argument here was that the massing and scale of the original building are part of what constitutes the character of the area – not only its aesthetic qualities.

Of course, a strong design alone is not enough to demonstrate that all of the relevant policy considerations have been taken into account. That’s why we produced a detailed design and access statement in order to tell the story of our design process, communicating how our character area appraisal and historic document analysis informed our eventual architectural strategy.

We’ll now take a look at design and access statements for replacement dwellings in the Green Belt. How can they be most effective?

Our approach to design and access statements embodies our philosophy as a practice: they demonstrate an interdisciplinary working of both planning and architectural expertise.

This is especially important for replacement dwellings in the Green Belt, because a complex policy argument has to be made in order to clearly justify what you are proposing.

In the case of our Metropolitan Open Land application, our design and access statement read more like a research document. We explored the site’s history, relying on the expertise of our heritage and archaeological consultants in order to communicate an accurate picture of the original building footprint.

While illustrating how our design responded directly to the particular conditions of the site, we also gave a significant amount of space to the analysis of Metropolitan Open Land (and as such, Green Belt) policy.

When it comes to replacement dwellings in the Green Belt, it will not serve you to downplay the potential of any harm caused to the Green Belt’s openness. This is because any development in the Green Belt, by definition of Green Belt policy, is understood to have the potential to cause harm to it.

The case you want to make is instead one that takes seriously any harm that your proposal might present to the Green Belt - and then clearly explains how the benefits of the development will outweigh that harm. As we’ve said, this may be accomplished by maximising the utility of the site, increasing its environmental benefit or improving the standard of design in the area.

It will be especially necessary to touch on this point if what you’re proposing presents an increase in footprint or volume. And again, if the original building is part of a listed complex or in a conservation area, it will be important to show that you have a comprehensive understanding of the value of the heritage asset on site.

In sum: the design should justify the proposal of a replacement dwelling in a way that enhances, rather than diminishes, the inherent value that is being articulated through the planning constraints in place.

As we’ve said, some councils like Cheshire East have their own guidelines for design and access statements. Since the council is particularly concerned about the impact of replacement dwellings on local character, they require that a separate Visual Impact Assessment be submitted in addition to a design and access statement.

This explores the character and appearance of the surrounding area, and demonstrates how the proposed scheme may be incorporated into the neighbourhood without resulting in significant harm to either the look and feel of the area or the quality of life of the residents.

Even if this is not explicitly required by your council, a strong design and access statement should explain how the character of the surrounding area has been assessed and make a point to address the proposal’s visual impact.

Alongside your application form and other supporting documents like consultancy reports, your design and access statement will therefore do the work of crafting a narrative around your planning submission.

Providing a compelling rationale for the proposal, while articulating your responsiveness to national and local policy prescriptions, will help your application have the strongest chance of success.

Urbanist Architecture is a London-based RIBA chartered architecture and planning practice with offices in Greenwich and Belgravia. With a dedicated focus on proven design and planning strategies, and expertise in residential extensions, conversions and new build homes, we help homeowners to create somewhere they enjoy living in and landowners and developers achieve ROI-focused results.

If you would like us to help you with planning for replacement dwellings in the Green Belt or other countryside settings, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

The Green Belt is one of the most contentious and misunderstood pieces of planning policy in England and it’s a topic we at Urbanist Architecture have a lot of experience working with. For this reason, we decided to pool our learnings and pen a book delving deep into the Green Belt from every possible angle.

‘Green Light to Green Belt Developments’ investigates the policy's biggest winners and losers, and explores its connections to climate change and the housing crisis, as well as what the future might hold, particularly now a new Labour government is in power. It also looks at the history of the policy and how it’s managed to endure while other policies have evolved and adapted with the times. Of course, it also identifies the exceptions and circumstances that exist for permitting development in the Green Belt, so you can better your chances of gaining planning permission.

We’ve written this book for anyone seeking a more rounded understanding of one of England's most debated urban planning issues, making it accessible to both industry professionals and the general public.

Whether you are a landowner in the Green Belt wishing to understand the potential for land value uplift or a developer planning to build new homes in the Green Belt, this book is an essential read. Order your copy now.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message