Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

So, you’re about to put in a planning application but don’t know where to begin.

Maybe this is the first time you’ve ever submitted a planning proposal, or maybe this is the first application you’ve put forward for a more substantial project.

Either way, you’re likely to come across conflicting information about what is actually needed from you. Beyond the council’s application form and your architectural drawings, some kind of written statement that justifies the design and explains how it complies with policy is generally encouraged, if not required.

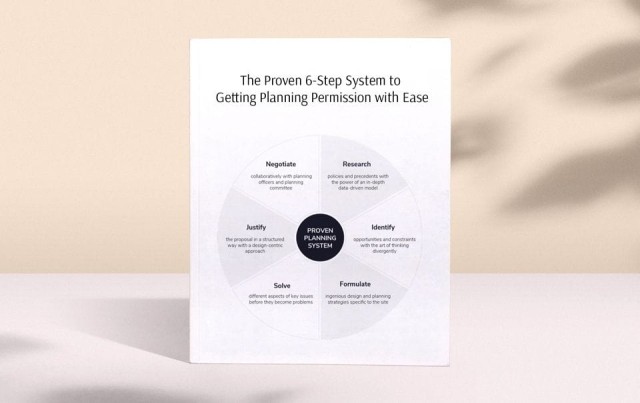

This takes the form of a design and access statement, a planning statement or – for major developments – both. We’re familiar with the government guidance on what’s expected, and in this article, we’ll explain what that is, hopefully making it clearer than councils do themselves.

But we’re also familiar with the way that councils work, from our professional experience. So we’ll also share our take on design and access statements, and tell you why our philosophy is that they’re worth the effort every time.

Let’s start simple. What even is a design and access statement, and when is one required?

The core idea of a design and access statement is that it allows applicants to explain how their development proposal responds appropriately to the site and its setting, and demonstrates how prospective users will access it.

By giving applicants a space to rationalise their design and identify the policy considerations that guided it, design and access statements are also meant to help local planning authorities more clearly make decisions.

Government guidance states that a design and access statement should accompany the following:

As it stands, applications for waste development, a material change of use, engineering or mining operations do not need to be accompanied by a design and access statement. Nor do applications to amend the conditions attached to a planning permission.

Still, our experience has led us to the conclusion that a design and access statement should be attached to every planning and prior approval application. If you don’t have some kind of written statement as part of your application, you are relying on a combination of the application form and the drawings to do all the work – and planning officers usually have no architectural training.

The way that we write design and access statements allows us to combine descriptions and planning policy justifications with our floor plans and elevations. In short, it gives us an opportunity to argue our case in a clear, well-researched way, using both words and illustrations to get our clients’ vision across. This embodies the value of our practice as a whole: the interdisciplinary working of planning and architectural expertise.

While we tend to go above and beyond the requirements, it’s important to note that there are some differences between the standard purpose of design and access statements that accompany applications for planning permission and those that accompany applications for listed building consent.

When it comes to applications for planning permission, a strong design and access statement should explain the principles and concepts that have been applied to the proposed design.

It must also demonstrate the steps that were taken to appraise the context of the development site, and then explain how that context has been explored. For example, were specialist consultants appointed to look at the traffic or ecological impact of what you are proposing?

What amounts to “context” will be specific to the circumstances of each application, and government guidance states that this should be tailored accordingly. Additionally, the relevant local plan policies that informed the design should be identified and explained. Any consultation undertaken in relation to access issues, such as highways impacts, must also be detailed.

As for listed building consent, the purpose of a design and access statement is a bit more specific. Beyond explaining how design principles and concepts have been applied to the proposed works, the design and access statement needs to address the special architectural or historic importance of the building, along with the particular physical features that justify its designation as a listed building.

The building’s setting must be addressed, as it does with an application for planning permission. Similarly, issues relating to access must be discussed. And finally, information on any consultation undertaken, and how that consultation ultimately influenced the development proposal, should be mentioned as well.

The guidance states that, where a planning application is submitted alongside an application for listed building consent, a combined design and access statement should address the requirements of both.

Whether it’s for planning permission or listed building consent, a design and access statement is very detailed. A successful one will go beyond the government’s basic requirements, telling the story of the design’s conceptual development and providing other helpful information like neighbouring planning precedents.

For bigger projects, it makes sense to accomplish this through a planning statement – a text-based document prepared by planning consultants that lays out the planning issues relevant to the site.

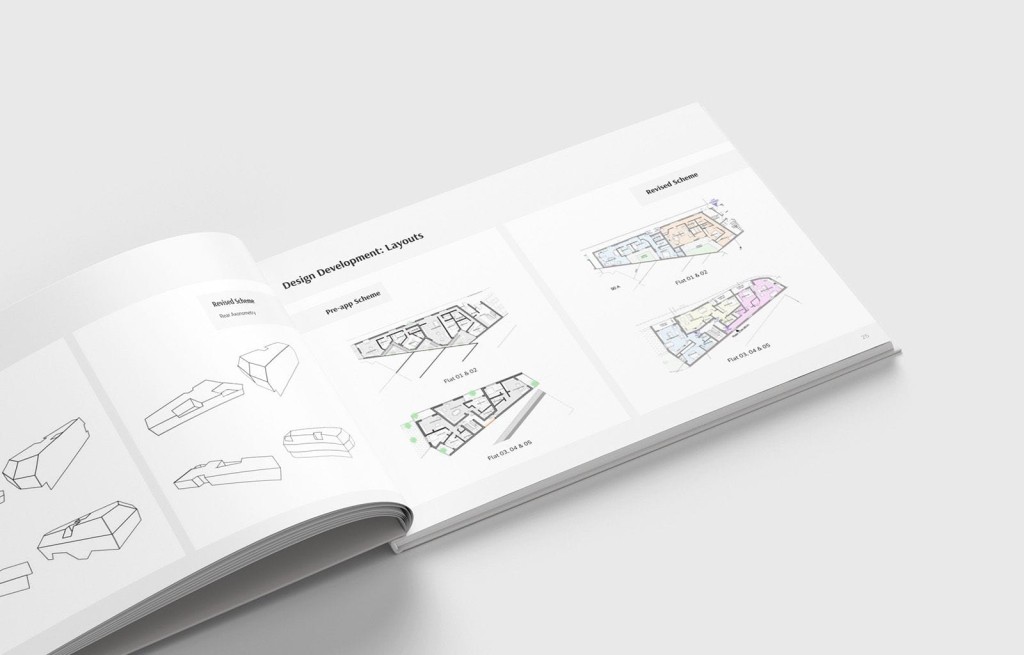

Alongside a planning statement, a design and access statement will then focus on the context and evolution of the proposed design, usually with plenty of illustrations, ranging from massing studies to photorealistic renders.

If you are trying to decide whether a design and access statement will cover everything you need or whether you also need a planning statement, then think about the scale and complexity of the development proposal.

Does it require substantial policy justification – as a “very special circumstances” (VSC) case in the Green Belt might? Or can the design logic, carefully informed by planning research, do all of the work?

Answering this question is something your planning consultants are here to do. All of our projects at Urbanist Architecture are given a bespoke application strategy that is most likely to be successful with the local council.

In addition to explaining the planning policy, design principles and material considerations that have informed the development proposal, every design and access statement should also address a few specific sub-categories. These include amount, layout, scale, landscaping, appearance, context, use and access.

Horsham District Council has written guidance on both detailed and outline applications, which we’ve synthesised – and added our takes to – here.

Design and access statements accompanying should explain the amount of development proposed and how it will be distributed across the site. For residential development, this means the number of proposed units, and for all other development, this means the proposed floor space.

The “amount” section should also discuss how accessibility is maximised for users to and between parts of the development. How does the proposal relate to the site’s surroundings?

This refers to the way that buildings, routes and open spaces are placed in relation to each other and to the development’s surroundings. A strong design and access statement should address the principles that underscored the choices in layout – particularly the locations of proposed development zones, blocks and building plots.

As with “amount”, the “layout” section should discuss how the need for appropriate access informs the design.

Horsham’s guidance states that the design and access statement should also consider the impact of the proposed design on the surrounding environment. How does the prospective layout shape relationships between public and private spaces? Does it help to foster safe, vibrant and successful places?

Moreover, when considering a development proposal’s broader environmental impact, it is important to note that a design’s layout can also have a significant effect on energy consumption and temperature control – and therefore, on carbon emissions.

Additionally, a building’s layout has inevitable social implications: many councils have policies on strategies to design out crime, for instance.

This section should therefore not only address the physical layout but the philosophies underpinning your design strategy – and include an acknowledgement of the effects that your design choices will inevitably have on the neighbouring context.

Referring to the height, width and length of a building in relation to its surroundings, “scale” is also relevant to this point. How will the size of building elements, such as entrances and facades, interact with the site’s context and relevant skyline?

A strong design and access statement should explain the philosophy behind height choices. How does the proposed building scale relate to the surrounding environment and line of development? And what about its relation to human scale, as people enter and exit the site?

Landscaping might sound a little grand, as if you were designing the grounds of a country house. But even if you’re just making changes to a terrace house, landscaping covers the back garden and the front garden or forecourt. In a design and access statement, applicants should address how landscaping makes clear the distinction between private and public spaces.

In light of the 2021 Environment Bill, particularly with its 10% Biodiversity Net Gain requirement, we should additionally be thinking about the greater function that the proposed landscaping can serve.

Does it offer sustainable drainage systems or other climate change adaptation strategies? If so, how will the ecology on site be maintained? These are all questions that the council will be asking, so it is important for them to be directly addressed.

And if your development proposal includes no landscaping element, simply address why landscaping is not relevant to the application.

Appearance, logically, has to do with the visual impact of the proposed development. Architectural style, material use and finishings are all relevant to this component.

These decisions all have an impact on the proposal site’s accessibility, especially with regard to lighting and colour choice. As such, this section should not only discuss what is proposed, but also explore why certain design philosophies eventually informed the decisions made.

Just as with layout, councils know that the questions underscoring aesthetic decisions also have social impacts. Who experiences a space and how they experience that space often have to do with the choices made in the urban design process.

It will therefore benefit both your application and your eventual project to think more broadly about the implication that seemingly aesthetic choices will have on the ways in which people interact with your site.

This point specifically asks how the site’s surroundings have influenced the proposed design choice. To properly examine this, your design and access statement should explain how context was appraised in the first place.

We often advise our clients on the appointment of specialist consultants in order to understand all of the factors relevant to their proposal. These could include such considerations as transportation, ecology, heritage or fire safety.

They could also include local community consultation if relevant, as well as discussion with building control or planning officers.

If pre-application advice was sought, it would be appropriate for any information gleaned from that report to substantiate the context component.

Horsham notes that the importance of this cannot be understated: understanding a development’s context is vital to producing good design and inclusive access. As such, applicants should avoid working retrospectively – that is, trying to justify a predetermined design after site assessment and evaluation.

In a good urban design proposal, your contextual research will organically shape the eventual design, and a strong design and access statement will merely detail the reasoning behind this.

While simple, use is equally important. Design and access statements are not only conceptual: they need to clearly describe how local context relates to the proposed use or mix of uses on site.

Use is a critical detail that underscores the accessibility of the entire proposal. Applicants should use their design and access statements as an opportunity to demonstrate how the proposed use maximises the capacity of the site and relates to its broader surroundings.

Finally, the “access” component of a design and access statement does the work of synthesising all of this information, clearly explaining how all users, regardless of age or ability, will be able to access the development that you’ve proposed. How does it link to the local public transportation network and wider street scene?

Relevant policy can also be referenced, specifically in reference to diversity of ability. Moreover, are emergency services able to reach the site? (To give an example, with a backlands development that has pedestrian access, how will the fire service or paramedics be able to get into the site in an emergency?)

The example we wanted to share with you for a design and access statement for a conversation area is for a carefully thought-through extension. There were several key points that we wanted to convey in this DAS.

The first thing we wanted to do is make a clear written case for the principle of development, explaining why our proposal was appropriate in the conservation terms as well as having no harmful effects on neighbouring properties and conforming with the spirit and the letter of the council’s planning and conservation area guidance.

But there’s only so much that words can convey. That’s why it was important to include plenty of illustrations showing the house from front and back. We used two different drawing styles - one sketchy, the other photorealistic 3D - to give the planning officers the best opportunity to understand how the changes to the house would look.

Again, it’s worth stressing that the people who will be judging whether your project looks right in context - the planning officers and possibly the planning committee members - most likely do not have architectural training.

Mindful of how important visual details are in an area prized for its built heritage, we included a page each going through the proposed front landscaping and rear landscaping.

We also had whole pages devoted to sustainability - which was an important component of this project - and the effect of the design on neighbouring properties, illustrated by our drawing showing the 45-degree line used to assess whether light will be lost.

All the information we were able to supply in the design and access statement meant that the council could be assured that the conservation area was being respected and even enhanced by the changes our client was asking for, and they were happy to grant planning permission.

The proposal here was to replace one house with two. The task for the design and access statement, then, was to show that two homes would make sense on this site.

That core task, though, needed to be broken down into different questions. The first: in the context of the street, would a pair of semi-detached houses seem strange?

That’s the kind of issue you can’t really address when filling in an application form. It is something you can potentially show with drawings or by including a selection of photographs with your application, but without a written explanation, it would be difficult to convey what the images were arguing.

With an illustrated design and access statement, you can include an aerial view showing the site in the context of the neighbouring properties, and then images focusing on the semi-detached and short rows of homes within the immediate vicinity, along with a written explanation of what is being demonstrated by these photographs.

That established the principle of what we were trying to do, but was there enough room for two houses, plus decent-sized gardens and enough parking spaces? And would those two houses look in proportion to the plot and the neighbouring houses, and not affect the quality of life in those homes by causing loss of light or privacy? All these points need to be dealt with in the DAS.

We also spent three pages discussing the appearance of the building, from front and back, along with showing examples of the materials that would be used. All to give the planning officers a comprehensive sense of what the houses would be likely, while balancing that with not providing unnecessary information.

Extra reading for the planning officers takes up their time and delays your decision, so the skill with putting together a DAS is working out what the council needs to know in order to assess your application and restricting yourself to that, rather than succumbing to the temptation to show off all the research you have done.

Our approach to design and access statements for new-build flats is best shown by the process of developing a planning submission for an irregularly shaped plot in East London that was occupied by redundant, run-down garages.

Our client sought to build new homes through the conversion of these garages into flats. While new contributions to housing stock are desperately needed in East London, the nature of the site meant that we still had a difficult case to argue.

The plot was constrained by its shape and surroundings: one half backs onto the rear of a medical centre and the other half borders a group of gardens. This meant that what could be built on the two halves of the site would have to be very different from one another.

The gardens – and the homes that they belong to – are entitled to light and privacy, and that was something we needed to consider. So part of the challenge was the task of designing something that looked like a whole, even though its two sections needed to have distinct attributes.

Our design and access statement therefore had to go beyond the technical requirements for a planning submission and do the work of storytelling. A bulk of our writing served to explain the theoretical development of our proposal, detailing the multiple rounds of pre-application notes that were received from the council and how we responded to them with care.

Expanding on the planning history of the site helped us demonstrate that we did our homework and were prepared to craft a design that tended to the concerns of both our client and the council.

We additionally used each of the sections detailed above – like ‘context’ and ‘use’ – as narrative opportunities to outline how our proposal would offer a substantial improvement to the site’s existing social and economic contribution. For instance, the appraisal site had no ecological value, and green building design was a core part of our development proposal.

Our design and access statement did not only explain such details as our proposed landscaping scheme – but it also embedded active research and policy analysis into the writing, to underscore how a biodiverse brown roof would function. For instance, its benefits would facilitate an increase in potential wildlife habitats on-site, while reducing stormwater run-off and improving the thermal performance of the building envelope. These are stated goals in both local and national planning policy, which the council would likely be sympathetic to.

To us, this project is a clear example of our design and planning professionals working together to form a successful proposal. Understanding the policy constraints of the site helped us craft a responsive design, and arguing our case in a well-researched design and access statement helped us communicate it visually to the council.

One exciting project that we currently have in the works is a pre-application submission for a Green Belt scheme in Yorkshire. Along with our drawings and other supporting documents like a character area appraisal, our pre-application engagement relied on a planning statement rather than a design and access statement.

As we’ve said, this is because the application scheme was for a larger development that, due to its complexity, required significant policy justification. At the pre-application stage, our design was indicative rather than set in stone, as we plan to rely on the council’s advice in order to craft a responsive planning submission later on.

Just like we did with the new-build flats described above, our planning statement for a Green Belt scheme centred on the iterative design process that informed our proposal. It was also an opportunity to tell the story about the way that we got there, demonstrating our careful eye toward Green Belt policy and development trends.

To do this, we highlighted four different master plans that we worked through to understand the best solution for the project. Each of these was conceived as a result of detailed planning research, exploring variations in massing and bulk. These are substantial considerations when pursuing any development in the Green Belt, because new building is generally considered to be inappropriate unless it meets one of a few key policy exceptions.

Even then, design proposals need to demonstrate that serious weight has been given to any prospective ‘harm’ that development would bring to the Green Belt – and that the proposal works in clear ways to outweigh that harm.

We therefore used the planning statement as an opportunity to talk through each of the four possible solutions, and then to explain why the one that we did choose came out on top. For example, it falls most in keeping with the character of the surrounding area, offering the lowest building density while also providing both private gardens and communal green space.

The planning statement also walked through each of the stated policy purposes of the Green Belt. In doing this, we analysed how the site currently contributes to these purposes, and then how the proposed scheme would contribute to these purposes. This is a clear example of our planning statement acting as a bespoke research document that goes beyond the written requirements of a planning submission.

Our argument was crafted to anticipate and address the council’s arguments around the site. This kind of writing requires the exact policy research skills that inform both our planning and architectural strategies.

Some councils, like the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, offer sample design and access statement templates that applicants can use to supplement their planning or listed building consent applications. We will note, though, that these fill-in-the-blank forms only offer a structure for the bare minimum level of detail that’s required to secure planning.

As we have demonstrated through examples of our work, a bespoke design and access statement that tells the story of a development proposal is the best way to communicate the necessary level of thought and policy knowledge in order to make a council feel confident in your proposal.

That’s why our services combine architectural design and planning policy research. We organise our design and access statements and planning statements into visually interesting and easy-to-understand documents that distil complex policy into plain language. We know what arguments speak to councils, and where to look for the housing and environmental data that will help back up the relevance of your development proposal.

So, if you have a project in the works, we’d be happy to help.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message