Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

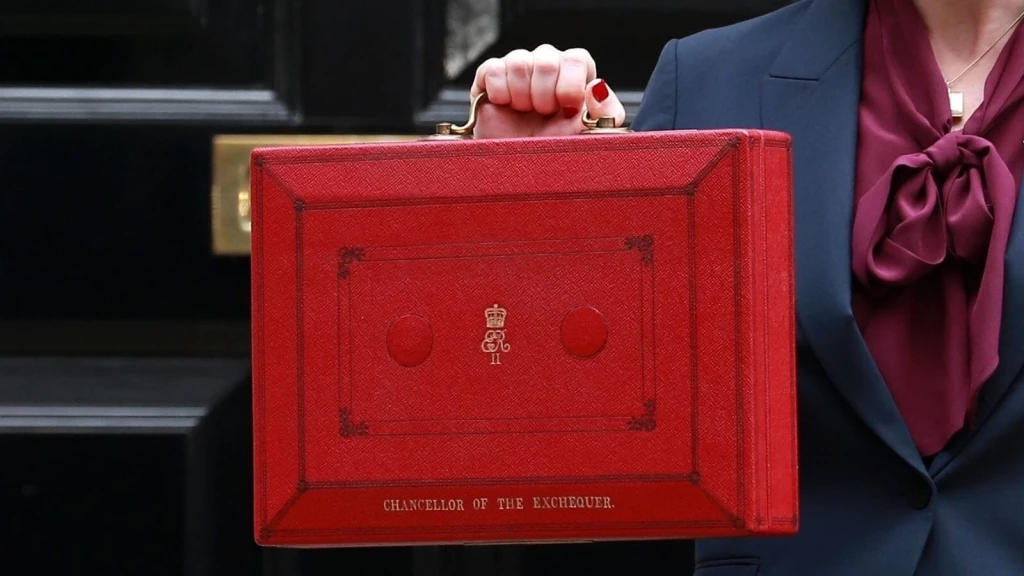

The Autumn Budget 2025 is, above all, a Budget about choices and trade-offs.

It raises the overall tax take again, leans on frozen thresholds to pull in revenue quietly over time, and tightens the squeeze on income linked to assets.

The politics is framed as “fairness”. The lived effect is simpler: more households and more businesses pay more, even when the headline rates barely move.

Housing feels this faster than almost anything else, because housing is where policy becomes personal. Tax changes show up in rents, deposits, buyer confidence, funding costs, and, ultimately, in whether schemes move from drawings to starts on site.

For the property sector, the Budget reads like a two-part offer.

On one side, it promises a planning system that is faster, better resourced, and more predictable. On the other, it resets incentives through landlord taxation and high-value property charges, signalling that the Treasury expects the market to adjust, not just the Exchequer to collect.

So the real question for developers and landlords is not whether this Budget is “pro” or “anti” housing. It’s whether the combined package makes delivery easier or harder in the real world.

With that framing in mind, here is our summary and analysis of the Budget’s key changes for property developers and landlords.

A striking feature of the Budget is how explicitly it treats planning delay as an economic drag, and “streamlined planning” as a productivity policy, not just a housing policy.

It repeats the Government’s aim of fast-tracking 150 planning decisions on major infrastructure by the end of this Parliament, alongside reforms intended to cut consenting timelines, including changes around judicial review and process.

For housing delivery, two announcements matter most:

There’s also a longer-horizon signal sitting behind the Budget’s planning narrative: new towns.

Done well, new towns are not a slogan. They’re a delivery programme: land assembly, infrastructure, governance, and a pipeline that holds its shape for a decade.

For the property sector, that shifts where opportunity sits, towards bigger strategic sites, clearer infrastructure sequencing, and a stronger role for public-private delivery vehicles.

But here’s the point that connects it back to the rest of the Budget. New towns don’t fail because the vision is wrong. They fail because the system cannot process complexity at pace.

If the Government wants new towns to become real stars rather than glossy announcements, it will have to match ambition with capacity, clear decision-making, and a planning system that doesn’t drift back into delay.

That is why the Budget’s focus on people, not just policy, matters. It is the Government finally saying the quiet part out loud: planning officers are national infrastructure.

But delivery capacity cannot stop at the planning desk. The next lever is skills. Alongside wider changes to tax, National Insurance and business rates, the Budget confirms that the Growth and Skills Levy will support apprenticeships for young people, including fully funding SME apprenticeships for eligible under-25s, and flags reforms intended to make the apprenticeship system simpler and more efficient.

If you want “more homes”, you have to want “more planners”, and not in the abstract.

Local planning authorities are where the housing target either becomes reality or becomes theatre. The Budget’s direction of travel is right:

But capacity is not the only issue. Quality matters too. In some cases, officer judgement and policy competence simply aren’t strong enough, which leads to defensive advice, missed opportunities and avoidable delay. That is why recruitment has to be matched by training and upskilling, so officers can apply updated policy confidently and consistently.

That feeds into the bigger delivery risk we deal with every week: you can announce outcomes faster than you can build institutional capability. Recruiting 350 planners is necessary. It will not be sufficient while slow-moving planning processes remain baked into overstretched teams, committee cycles and fragmented consultee responses.

What would make it sufficient is the unglamorous stuff:

Planning capacity is only half the equation. The other half is whether the industry can actually translate consents into completions, which comes down to skills, supervision, and day-to-day site discipline.

Funding SME apprenticeships for under-25s is a sensible move, but it only pays off if it targets the bottlenecks we actually see on sites: retrofit skills, low-carbon detailing, MMC quality control, and competent site management.

That same principle applies to how we train, not just what we train for. There is no value in scaling an apprenticeship pipeline that prepares people for yesterday’s delivery model.

The system needs to bake in modern practice as standard: digital delivery, AI-assisted coordination, reality capture, and agile construction monitoring that flags issues early, protects quality, and keeps programmes honest, especially during RIBA Stage 5, where design intent either survives contact with site reality or it doesn’t.

Because the step-change the Government is asking for is not only an issue of labour supply. It’s an issue of capability and productivity, end-to-end, from consent to construction.

And that brings us back to the start of the pipeline: if planning remains underpowered, everything downstream slows. Planning must be treated as a profession to retain and empower, not just a headcount target to recruit.

The phrase “default ‘yes’ for homes near train stations” is not a detail. It’s a worldview.

In practice, this points towards a development model that prioritises:

This interacts directly with the conversation around Grey Belt land.

Even where Grey Belt is politically framed as the pressure valve, the more scalable, less contentious supply strategy is often this: build near infrastructure that already exists, and make that the new normal.

But the two agendas rise or fall on the same thing: whether local decision-making applies updated national policy consistently, or defaults back to defensive refusal and appeal-led delivery.

Read together, the station-led “default yes” signal and Grey Belt policy are two routes to the same outcome: faster housing delivery in the right places.

Grey Belt land may have a role, particularly where land is genuinely degraded, poorly performing, or already compromised. But the “default yes” signal suggests the Government is trying to reduce how often it needs Grey Belt policy to do the heavy lifting. That is strategically smart.

If we get station-led densification right, including design quality, daylight, schools capacity, GP access, and public realm, then Grey Belt becomes targeted, not desperate. That said, if station-led densification is to reduce pressure on Grey Belt in practice, it has to be delivered at scale and at quality. That means schemes that can survive the usual pressure points while still remaining viable.

However, there is a delivery problem we are now seeing repeatedly on live Green Belt and Grey Belt projects. Many local planning authorities are still reading the updated policy through an old Green Belt reflex, and the consequences are direct: delay, cost, and preventable appeals.

What we are seeing on the ground is a simple misalignment between what national policy now expects and how some local authorities are applying it. The guidance exists, but it is too often filtered through an older Green Belt reflex, which pre-determines the answer before the merits are tested. The result is predictable.

Sites that demonstrably meet the Grey Belt assessment are still treated as standard Green Belt, assessed through a traditional “Green Belt openness” frame, and discouraged at the pre-application stage. Applicants then have to appeal, wasting time and money, and pushing delivery back by 6 to 24 months.

These are not technicalities. These misapplications fundamentally shape whole case trajectories and outcomes. They also distort the process by baking the wrong test into the officer narrative from day one, introducing confusion, avoidable cost, and placing applicants at a disadvantage through no fault of their own.

And it shows up clearly in Grey Belt appeal decisions. Since the updated NPPF came into force, the success rate for major residential Grey Belt appeals has been strikingly high, with inspectors repeatedly allowing schemes that were discouraged or refused locally on the basis of the wrong policy test.

If the Government is serious about delivery, it should not accept a system where approvals happen mainly at appeal. That is a costly, slow-moving route to permission that delays housing for months, consumes public resources, and undermines confidence in the planning process.

The Budget ties itself to London’s housing emergency package announced in October, positioning it as a near-term viability intervention intended to boost delivery, including affordable homes, in the coming years. That emphasis is not accidental. It reflects a simple reality: London's housing market is not just cooling, but fundamentally stuck.

This paralysis has been building for some time. Confidence has weakened at both ends of the housing chain, creating a problem that extends beyond property values on paper. Too few people feel able to move. Owners hesitate to sell, doubting they will achieve prices worth accepting. Others find themselves locked in by prohibitive moving costs, while first-time buyers remain locked out without family support.

Against this backdrop, the new annual surcharge on homes above £2 million sends another signal that high-value property will carry heavier ongoing costs. In London, this measure reaches beyond trophy assets into a wide slice of family housing in prime areas.

While the prime and super-prime market may not be transformed by this measure alone, signals matter profoundly in a low-confidence market. They shape negotiations, delay decisions, and ultimately reduce turnover.

The consequences cascade from there. When turnover slows, delivery slows. London's structural affordability challenges mean that interest rate changes bite harder and activity cools sooner than elsewhere. This feeds directly into real estate confidence and lending appetite, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of stagnation.

This is why London's housing emergency package matters in practice. It is designed to restart activity and help stalled schemes move from viability spreadsheets to starts on site. In our London's housing emergency package analysis, we explained the package as five linked interventions, not one silver bullet:

The key point for developers is that it is not a philosophical U-turn on planning. It’s a delivery rescue route designed to convert stalled paper permissions into real starts, and convert theoretical affordable homes into built affordable homes.

Two moves sit alongside this, and they matter for delivery confidence:

Flexibility is only useful if it is targeted at the right constraints.

There is a real distinction between overly rigid interpretations of guidance that quietly kill schemes and baseline safeguards that protect liveability. Minimum space standards sit firmly in the second category.

That is why any “flexibility” agenda must be careful. We can support smarter design judgement around layouts, cores, and constrained sites, but minimum space standards should remain non-negotiable if the aim is a healthier housing market, not just a higher unit count.

The Budget and the London package reinforce each other, but they also create a predictable new bottleneck:

A surge of applications, followed by overwhelmed borough teams.

That is why the Budget’s emphasis on planning officers matters so much. Without Local Planning Authorities that can process volume quickly and consistently, London’s housing emergency package risks becoming a policy that creates hope, then creates delay.

There is also a transparency issue that needs addressing, because it sits under the viability debate.

Many boroughs are holding large balances of unspent developer contributions (CIL & S106), raising legitimate questions about whether the existing infrastructure burden on developers is proportionate, timely, and effectively deployed. When contributions are collected, but delivery lags, the system breeds mistrust on all sides: residents feel nothing improves, developers feel they pay twice, and boroughs still struggle with capacity.

There is also a deeper strategic opportunity here.

If London’s package proves that viability may be “unstuck” without permanently lowering standards, it becomes a template:

And if it succeeds, it changes the politics of housebuilding in London: not by winning arguments, but by producing outcomes.

This Budget is not just about planning permission. It is about incentives, and the deliberate move to narrow the gap between taxation of work and taxation of assets. For property, that shows up fastest in household spreadsheets and landlord cashflow.

In practice, three levers matter most for the market: frozen thresholds, higher tax on rental income, and the new annual surcharge on high-value homes.

Threshold freezes for income tax and National Insurance mean more people drift into higher effective rates over time. That matters for housing because it squeezes tenant affordability and investor confidence at the same time.

On top of that, tax rates on income generated from property, savings and dividends rise as part of a wider package of increases that, in practice, lands heavily on middle and upper-middle earners.

The Budget confirms separate tax rates for property income from April 2027, set at:

For many landlords, this is a direct reduction in post-tax yield, especially where borrowing and maintenance costs are already high.

These changes are material for landlords, whether you’re a portfolio landlord, an accidental landlord, or an overseas owner under withholding arrangements.

The sector’s concern is simple: higher tax on rental income changes behaviour, usually in one of three ways: landlords raise rents where they can, restructure or repurpose the asset, or sell. Industry bodies are already warning of pressure on rents and on rental supply as landlords re-run the numbers.

The Budget also sets up a new High Value Council Tax Surcharge on homes worth £2 million+ from April 2028, with a consultation to follow.

The charges spread across four price bands:

Despite the rhetoric, a “mansion tax” can coexist with a system that feels upside down. Council Tax in England is still anchored to 1991 valuations, with Band H defined as “over £320,000” and no higher bands above it. That design choice weakens the link between today’s market values and annual property tax bills.

In practice, that caps the tax base in the places where prices have run furthest, such as Mayfair, Belgravia, Knightsbridge, St James’s, Chelsea and Pimlico, while many lower-value authorities still levy comparatively high annual bills.

The Government’s own factsheet makes the problem plain. Under the current system, the average Band D bill across England is higher than what a £10m property in Mayfair effectively pays through Westminster’s Band H charge. The new High Value Council Tax Surcharge is designed to tighten that anomaly, but it is layered on top of a structure that remains only weakly progressive.

On today’s numbers, that is how you end up with a £5m townhouse in Prime Central London, for example in Mayfair or Belgravia, paying under 0.2% of its value each year in local property tax even after the new surcharge.

Westminster Band H is £2,034.36 in 2025/26, and the £5m+ surcharge is £7,500, totalling £9,534.36, which is about 0.19% of £5m.

Meanwhile, a £150,000 Band B home in Stoke-on-Trent pays £1,616.49 in 2025/26, which is roughly 1.1% of its value.

The surcharge narrows the gap at the very top, but it does not overturn it. The system remains one where a modest house in a lower-value city such as Stoke-on-Trent can face a property tax burden several times heavier, in proportional terms, than a multi-million-pound home in the capital.

That is the fairness critique. The next question is how the surcharge changes market behaviour.

For Prime Central London, the behavioural effects will likely cluster around the threshold zone. True super-prime may absorb it as a running cost. The £2m to £2.5m segment is where liquidity, turnover, and pricing sensitivity may show first.

One response we’re increasingly seeing, even before the Budget landed, is landlords exploring house-to-flats conversions as part of wider portfolio reshaping and “tax planning” conversations. It often starts with an accountant, but the moment you consider conversion, you are in planning territory, and councils will judge the outcome on liveability and policy compliance.

That means unit sizes, daylight and outlook, private amenity, access and refuse arrangements, and whether you are creating decent long-term homes rather than squeezing unit counts.

If a conversion improves housing supply and quality, many councils and inspectors can support it. If it produces smaller, poorer homes, the system increasingly resists it, and rightly so.

So if you’re considering it, be clear-eyed: converting a house into flats is not a paperwork exercise. It needs a planning strategy that stands up in your borough, flats that meet minimum standards and let or sell without constant friction, and a building that feels professionally refurbished rather than aggressively carved up.

Get it right, and you end up with a stronger, easier-to-manage asset. Put simply: you stop reacting to policy and start steering your portfolio.

At the top end, the surcharge shifts behaviour around thresholds. At the bottom of the chain, ISA policy shapes how quickly first-time buyer deposits are built.

The annual ISA cash limit is set to fall to £12,000 from 6 April 2027, within the wider £20,000 ISA limit, with a consultation in early 2026 on a simpler first-time buyer ISA-style product.

For the wider housing market, this matters because first-time buyer deposits are not built by speeches. They’re built with surplus cash.

This section is best read as a timing problem: the tax changes land before delivery conditions improve.

There is another structural feature worth calling out: a noticeable amount of the tax raising is back-loaded towards the end of the Parliament.

That may be deliberate. It gives room to talk about stability now, while pushing the sharpest changes into later years. But it also means the property sector is dealing with two things at once:

In the public reaction, you see a familiar split. Some view the approach as punishing work and aspiration, and worry that almost everyone ends up paying more as thresholds remain frozen. Others see it as a long-overdue rebalancing between labour income and asset-linked income.

There is also a deeper critique that matters for planning and delivery: Budget “headroom” is only as real as the forecasts it rests on. If growth disappoints, the temptation to come back for more revenue rises. For developers and landlords modelling long-range decisions, that uncertainty is itself a cost.

History shows what happens when property taxation distorts incentives rather than simply raising revenue. The most striking British example still shapes our buildings today.

In 1696, a Window Tax was introduced, intended as a rough proxy for wealth. Over time, especially in cities, it hit tenants hardest because landlords controlled the fabric of buildings and could reduce liability by reducing windows. The public health impacts of reduced light and ventilation became widely documented, and the tax was eventually repealed in 1851.

It is often claimed that “daylight robbery” comes from this era, though the phrase’s origin is disputed, so don’t rely on it as a serious policy fact.

But the planning lesson is still priceless: tax something, and you change it; tax it badly, and you distort everything around it.

That is the risk with property taxation now.

Raise taxes on rental income, and some landlords will exit, some will incorporate, some will raise rents, and some will stop improving stock.

Add a high-value surcharge, and you may reduce turnover at the top end, which then reduces liquidity and transactional friction down the chain, even if the super-prime segment shrugs it off.

From a fairness lens, the direction is coherent: asset income taxed closer to labour income.

If rental supply tightens while the planning system is still ramping up capacity, the politics of housebuilding hardens, and delivery becomes harder, not easier.

From a delivery lens, the test is whether it unintentionally worsens the rental supply problem at the very moment the Government is asking the UK construction industry to build at pace.

Among the quieter but most practical announcements is the Landfill Tax.

The Chancellor signalled that the Government had listened to the housebuilding industry and would not converge towards a single rate, while still preventing the gap between the standard and lower rates from widening.

The direction of travel is clear:

This matters for brownfield sites because landfill cost is not an abstract environmental lever. It is a line in your enabling works budget, sitting right next to remediation, utilities upgrades, asbestos, ground conditions, and access works.

And it matters because brownfield viability often fails before a scheme even reaches the “design” conversation. Too many sites stall at the enabling stage, not because the planning case is weak, but because the abnormal cost stack is too heavy.

For housebuilding, stepping away from rapid convergence to a single landfill rate is an implicit admission that, right now, the cost stack is already too fragile.

But the outcome also signals a direction of travel: the Government still believes the lower rate is too cheap, and it is nudging the market toward higher disposal costs over time.

That creates two strategic imperatives for developers and design teams:

If the Government wants brownfield to carry more of the housing burden, it must keep aligning fiscal signals with delivery tools. Otherwise, we get the worst outcome: higher costs and no additional supply.

The Budget is explicit about the 1.5 million homes ambition in England, and it repeatedly frames planning reform as the delivery mechanism, not a side policy.

In the Budget document itself, the Government points to NPPF reform as a material economic intervention, citing an additional 170,000 homes and a 0.2% GDP boost by 2029-30, and later goes further by leaning on the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s judgement that the updated NPPF could lift annual housebuilding by around 30% by 2029-30, taking net additions to a 40-year high.

Alongside that, the forecast narrative underlines the cycle problem. The OBR expects net additions to the UK housing stock to fall to a low of 215,000 in 2026-27, before rising sharply to 305,000 in 2029-30, explicitly “reflecting the impact of planning reforms”.

Over 2024-25 to 2029-30, the OBR expects 1.49 million cumulative net additions across the UK. The point is not just whether the headline ambition is theoretically reachable, but whether the timing works: delivery dips before it accelerates, and that mid-period trough is exactly where confidence, funding and starts tend to wobble.

This is where optimism has to be earned.

A million-plus homes over a Parliament is not trivial. But it is also not automatically a victory, especially if delivery concentrates in places already built, while constrained areas stay constrained.

From our day-to-day work securing planning consents and troubleshooting stalled schemes, the pattern is consistent: delivery fails at predictable points. I’d argue the Budget is trying to solve this with a three-part engine:

That is a credible architecture for change.

But the mission will succeed or fail on governance: whether decision-making becomes more expert, more predictable, and more accountable, especially in the places where committee politics and under-resourcing have created chronic under-delivery.

And this is where the harsh critiques intersect with delivery. Some argue the country is drifting towards “tax more, spend more”, relying on forecasts to justify headroom, and asking the productive economy to carry an ever-growing burden.

Whether you agree or not, the planning takeaway is practical: if growth is fragile, housing delivery has to be less fragile too.

The Window Tax reminds us that policy reaches into bricks, windows, rents, and health.

This Budget is doing something similar, but with modern tools:

The immediate takeaway is simple: the planning system is being positioned as the delivery mechanism for the Government’s promise of change, so the planning system will now be judged by outputs, not intentions.

At Urbanist Architecture, we help clients respond to exactly these moments, when planning reforms and viability tools change the rules of the game, and where that plays out most sharply on real projects such as house-to-flats conversions, small-site development, Grey Belt schemes, and proposals shaped by Green Belt rules.

If you’re weighing up what this Budget changes for your site, we can help you turn the policy noise into a practical plan and a credible route to consent.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message