Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Walk through Birmingham's evolving neighbourhoods and you will witness a peculiar British phenomenon: construction without consequence. Tower cranes perform their mechanical ballet. Marketing hoardings promise "vibrant communities."

Council planning documents speak of "sustainable development" and "community benefit." Yet something fundamental is missing from this picture of urban transformation. And it's costing you more than you realise.

In fact, the infrastructure that was supposed to accompany all this development is not delayed or postponed, but simply absent.

This isn’t about red tape or minor glitches. It’s about a deeper failure: councils collect billions for infrastructure yet rarely build it. That disconnect undermines the very premise of urban growth.

In this article, I will show how separating development from infrastructure doesn’t just leave gaps in amenities but breaks the promise of planning itself, producing fragmented housing estates instead of real communities.

I will also examine how billions in unspent developer contributions accumulate in council accounts, why affordable housing delivery collapses under current rules, and what international models reveal about fixing Britain’s broken system.

Let’s begin.

Unspent developer contributions are funds collected from developers for infrastructure that remain unused in council accounts.

These contributions come through two main mechanisms:

Together, they generate billions each year, yet too often the money is not translated into the facilities that make new neighbourhoods work.

The mechanism of failure is straightforward. Money accumulates because the rhythm of infrastructure delivery rarely matches the way contributions are received. Councils wait years to pool sufficient funds, large projects stall in lengthy design and procurement stages, and phased developments release cash in instalments that don't align with local needs.

With no national system to coordinate spending, much of the money drifts into bureaucratic limbo whilst communities deal with overcrowded schools, worn-out roads, and missing public spaces.

This isn't merely an administrative delay. In fact, it's compounding damage. The longer developer contributions sit idle, the more infrastructure costs escalate, eroding the value of the funds. Meanwhile, every unbuilt playground, every undelivered bus route, every delayed health centre deepens public mistrust in planning and local government.

The numbers tell a story of institutional failure on a scale that should trigger parliamentary inquiries and resignations.

You may be surprised, but councils across England and Wales are sitting on over £8 billion in unspent developer contributions, a stockpile that exposes the widening gap between collection and delivery.

This comprises nearly £2 billion in Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) funds and over £6 billion from Section 106 agreements, according to Home Builders Federation research from 2024.

This systematic data collection, based on Freedom of Information responses from 208 local authorities representing approximately 60% of all councils, reveals what organisational theorists call 'accountability diffusion,' where responsibility becomes so distributed across multiple council departments that no individual or institution can be held liable for systemic failure.

The Times revealed in September 2025 that £574 million from CIL receipts remains completely unallocated. These funds are not assigned to future projects, not earmarked for specific improvements, but are simply floating in council reserves. The newspaper’s investigation suggests councils could be earning millions annually in interest from these unspent funds.

Even a modest 2.5% treasury-style return on £574m is ~£14.4m/year. That’s one secondary school or ~120–150 classroom upgrades every year without touching the principal.

Some district councils hold unallocated CIL reserves exceeding tens of millions of pounds. That is more than many councils' entire annual operating budgets, sitting idle while residents navigate potholed roads and overcrowded schools.

But here is where it gets worse.

The HBF's analysis reveals that 26% of these unspent developer contributions have been held for more than five years. That is approximately £1.6 billion that has been sitting in council accounts since before 2019, through a pandemic, through a cost-of-living crisis, and through mounting infrastructure pressures that councils claim they cannot afford to address.

The temporal dimension of this hoarding is stark when considered through the lens of compound infrastructure decay: every year of delayed maintenance increases future repair costs exponentially, meaning the purchasing power of these funds diminishes while the infrastructure deficit grows.

This represents what economists term 'marginal utility decay,' where each additional cost imposed on development has disproportionate effects on viability as margins compress, while compound infrastructure decay means every year of delayed maintenance increases future repair costs by approximately 15-20% according to civil engineering standards.

The concentration of these funds reveals a system that rewards dysfunction. The data indicates a rapidly accelerating problem; the HBF's estimate of unspent Section 106 funds more than doubled in a single year, from £2.8 billion in 2023 to an extrapolated £6.3 billion in 2024.

This suggests the rate of collection is far outstripping the capacity or willingness to spend, and the blockages within the system are worsening over time.

Analysis by the HBF reveals that the 20 councils with the largest Section 106 reserves collectively hold around £2 billion in unspent contributions.

Oxfordshire County Council leads with £287.5 million in unallocated funds, according to the industry body's Freedom of Information requests. Far from being cash-strapped authorities in declining regions, these councils oversee some of Britain's wealthiest areas, where development pressure and infrastructure demands are most acute.

This hoarding of funds represents a critical misunderstanding of infrastructure as a catalyst for growth. Instead of being viewed as an investment that unlocks economic potential and enhances quality of life, it is treated as a transactional cost to be deferred. This approach ignores the time-value of infrastructure.

Why does this matter to you?

A school built today prevents overcrowding now, not in five years when the funds are finally spent. A park built alongside new homes fosters community from day one. The failure to act is not just a delay, it is a permanent loss of opportunity.

The magnitude of this failure becomes clear when examining what these unspent developer contributions were legally obligated to deliver.

The unspent affordable housing contributions of £817.1 million could have delivered approximately 11,000 affordable homes, according to HBF’s analysis using Homes England's standard delivery costs. That's enough to house every family currently in temporary accommodation across multiple British cities. These missing homes perpetuate what housing researcher Anne Power identified in "Estates on the Edge" as spatial marginalisation, where disadvantaged populations concentrate in inadequate accommodation.

Education infrastructure tells an even starker story. According to the HBF, the £2 billion in unspent education contributions could have created around 126,000 new school places, based on Department for Education cost benchmarks.

Instead, we have "bulge classes" in corridors and temporary classrooms becoming permanent fixtures while millions designated for education sit untouched. Schools are more than learning spaces. In fact, they're community anchors. Their absence erodes social capital.

Transport and highways contributions could have repaired approximately 12.6 million potholes, according to HBF calculations using Asphalt Industry Alliance repair costs. Meanwhile, councils plead poverty when residents complain about vehicle damage. The deterioration creates what transport planners term "induced maintenance debt," where deferred repairs accelerate adjacent infrastructure degradation through increased vibration and water infiltration.

The £873 million in unspent social infrastructure contributions could have funded around 1,000 sports halls and 4,700 community games areas, according to the HBF's analysis based on Sport England facility costs. At a time when we face obesity epidemics and mental health crises, the infrastructure that could address these challenges remains unbuilt, whilst funds accumulate interest.

These figures aren't merely a list of unbuilt projects.

London, with its world-class expertise and immense development pressure, should be a model for effective infrastructure delivery. Instead, it exemplifies a sophisticated form of failure, where the system’s very complexity becomes an obstacle to creating a cohesive urban fabric.

The city's predicament can be summarised in a paradox: it collects vast sums of money, spends them with little predictability, and operates 33 parallel borough-level systems that effectively diffuse accountability.

The success of the Mayoral CIL, which raised approximately £726 million for the Elizabeth Line, provides a powerful lesson. This city-wide, single-purpose levy worked precisely because it was tied to a tangible, transformative project with a clear mandate and political accountability. It represents a rare instance of strategic, infrastructure-led planning in the modern British context.

In stark contrast, the borough-level CILs operate in a fragmented and opaque manner. London's 33 boroughs collectively collect over £400 million annually, with an unspent balance conservatively exceeding £800 million. This fragmentation is not an accident but a design flaw. It creates a patchwork of competing priorities and prevents the funding of strategic, cross-borough projects that are essential for a functional metropolis.

For example, while a borough like Tower Hamlets charges rates varying from nil in strategic sites to £200 per square metre in prime areas, it is nearly impossible to trace that money to tangible, corresponding improvements in the local urban environment. The funds become absorbed into council budgets, disconnected from the specific developments that generated them.

The result is a focus on minor, reactive maintenance rather than proactive, transformative investment. Camden’s expenditure of around £4 million on 'footway improvements' - essentially fixing pavements - from a multi-million-pound annual CIL collection is a case in point.

While necessary, this piecemeal approach fails to address the larger strategic needs of the urban fabric, such as creating new green spaces, improving public transport accessibility, or building new social infrastructure.

The same short-termism colours national debates on building homes in London's Green Belt, where arguments over land release obscure the deeper failure: even where funds are available, councils have failed to deliver infrastructure that would make such development sustainable.

The City of London stands out as a positive example with transparent governance and regular deployment, but it is the exception that proves the rule. If the capital, with its resources and expertise, cannot deploy its funds effectively, the picture beyond London is hardly more reassuring.

Beyond London’s fragmented borough system lies a wider failure that is just as striking. Infrastructure Funding Statements from Birmingham, Leeds, and Newcastle reveal tens of millions in accumulated CIL receipts, yet the lived reality on the ground is one of cracked pavements, congested junctions, and tired public spaces.

These are not hollowed-out post-industrial towns. They are regional economic engines with well-resourced planning departments. Yet the same pattern emerges: money is collected, reserves grow, but little is delivered in the way of transformative investment.

Consider Birmingham. Since adopting CIL in 2016, the city has raised significant revenues under a charging schedule that imposed high rates in prime zones and nil rates in weaker markets. Yet official reviews admit the persistent problem of funds remaining unspent, with receipts locked in the system rather than being channelled into visible projects.

Leeds illustrates the same weakness. In 2023/24, it recorded nearly £10 million in CIL receipts, yet the council continued to carry forward “allocated but unspent” balances. In Newcastle, the 2021/22 funding statement set aside £800,000 for strategic highways and junction improvements. These commitments have proved slow to materialise while the city’s infrastructure continues to wear down.

Manchester provides a variation on the theme. The city only adopted CIL in 2022, making it one of the last major authorities to do so. Its delay spared it the rigidity of the levy but left it reliant for more than a decade on piecemeal Section 106 agreements. The result was not a strategic programme but a patchwork of site-specific obligations that could never deliver the scale of coordinated investment the city requires.

Meanwhile, the government's push for planning permission without planning committees offers a rare improvement in a broken system. Reforms now delegate decisions on developments of up to nine homes directly to planning officers, bypassing committee review entirely. Some may argue this removes democratic oversight, but the reality is that committees have proven neither effective nor efficient.

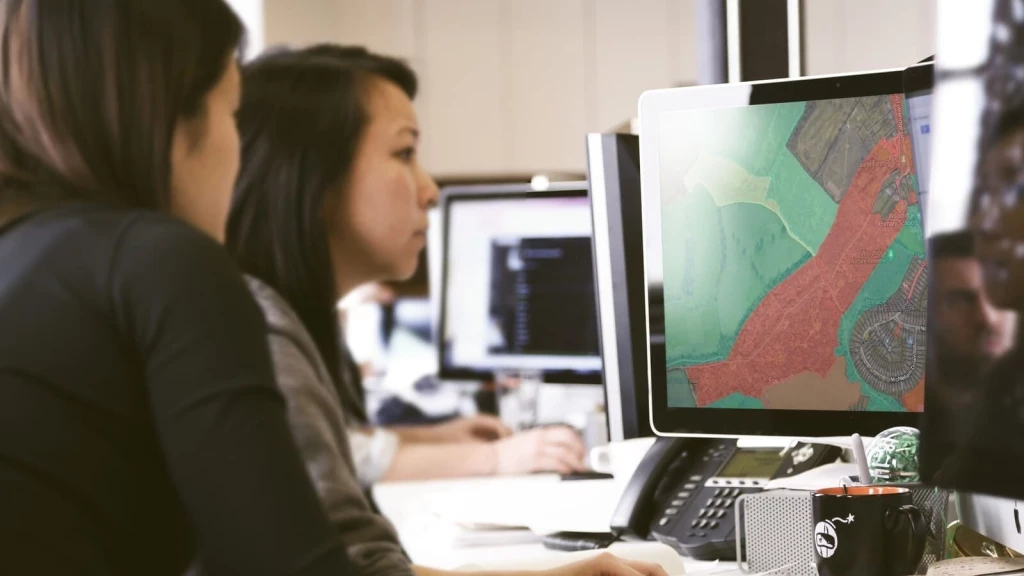

From our own experience as residential architects designing projects across London and the UK, we've seen how committees delay viable schemes for months through repeated deferrals whilst waving through poorly designed developments that tick procedural boxes. The process adds time without adding value, which means that schemes that comply with policy face endless questions, whilst those with genuine design flaws progress if the developer has navigated the political landscape effectively.

The real test of these reforms, however, is whether they address infrastructure delivery. Streamlining approvals is worthless if councils continue hoarding billions of unspent developer contributions. Faster permissions without deployed funds simply accelerates the production of housing estates built without schools, transport links, and community facilities. A system optimised for speed of approval but not delivery of infrastructure remains fundamentally broken.

And the evidence confirms this is precisely what's happening. Across England, councils treat CIL not as a ring-fenced programme for long-term infrastructure but as a flexible revenue source absorbed into their budgets.

Camden demonstrates the consequences. In 2023/24, it spent £4 million of its Strategic CIL on “footway and carriageway improvements,” essentially pavement repairs, despite collecting many millions more. A mechanism designed to fund bold investment in the future of cities has been reduced to a tool for routine maintenance, its potential lost to short-term fixes.

This is not simply an administrative delay. It is a profound policy failure that abandons strategic planning in favour of fragmented, developer-led urbanism. The authorities best placed to shape coherent urban futures have instead become reactive, responding to individual applications while allowing long-term vision to wither.

The question remains: is your council following the same path?

So let’s turn that frustration into something practical. If you want to see where your city’s money is sitting - and whether it’s inching toward real projects - run this quick 20-minute audit this week:

Use those steps, and you will likely see the same pattern locally: balances rising, schemes slipping, and residents forced to chase basic answers through confusing processes.

At that point, the issue stops being a spreadsheet problem and becomes a household problem, with fines, stress, and avoidable bills. This is why the human cost of this bureaucracy matters more than the headline totals. Because behind every unspent million is a real family facing real consequences.

Behind these billions lies a more disturbing reality: ordinary families crushed by administrative machinery.

Take West Berkshire Council's CIL scandal. According to council records and local media reports, residents who missed procedural deadlines by as little as one day faced penalties of up to £40,000. The complexity of exemption forms, which the council itself later acknowledged as problematic, turned minor oversights into financial disasters. One resident faced a £40,000 charge for missing a single tick box on a granny annexe form.

But here's what exposes the system's true priorities: when forced to review these cases following public pressure, West Berkshire found six out of seven homeowners had been unfairly charged. The council refunded between £12,000 and £40,000 per household, according to council meeting minutes from 2023.

Think about that mathematics. These weren't edge cases. They represented an 86% error rate in the council's favour.

Meanwhile, the council maintains dedicated teams to pursue these penalties whilst claiming insufficient resources for infrastructure delivery. They can fund enforcement officers to chase paperwork errors, but not project managers to build the schools and roads the money was meant to provide.

This isn't incompetence. It's institutional design. The system rewards revenue collection with dedicated resources and swift action, whilst infrastructure delivery faces no deadlines, no penalties, no consequences.

What emerges is a particularly British form of injustice: bureaucratic precision weaponised against residents, whilst the same bureaucracy claims helplessness regarding its core obligations. The infrastructure these penalties were meant to fund? Still unbuilt. The families financially devastated by administrative errors? Left to navigate a "discretionary review process" the council only introduced after media exposure.

Consider the architectural parallel here. Just as Victorian workhouses were designed to punish poverty rather than alleviate it, our modern planning system punishes minor administrative errors whilst rewarding institutional hoarding. The physical infrastructure of enforcement (offices, staff, systems) exists in abundance. The physical infrastructure for communities remains theoretical.

The result is a system architected to extract rather than deliver. Whether through punishing residents for paperwork errors or strangling viable schemes with impossible demands, the levy system distorts outcomes at every level.

Here's the mathematical reality that kills development before it starts.

Every project operates on razor-thin margins where a 5% cost increase can flip viability. According to analysis by the British Property Federation, CIL represents a fixed upfront cost averaging 3-5% of development value, regardless of market conditions. Layer this onto land costs, construction, professional fees, and the developer's required profit margin, and the arithmetic becomes unforgiving.

The paradox intensifies on brownfield sites, precisely where government policy directs development. These sites already carry what surveyors term "abnormal costs": contamination remediation, demolition, and complex ownership structures. According to the HBF, brownfield developments face additional costs averaging £200,000 per hectare compared to greenfield sites. Add CIL charges, and the mathematics simply doesn't work.

This isn't merely a developer problem. It fundamentally reshapes our cities.

When brownfield sites become financially unviable, development often shifts to greenfield locations. This is particularly evident in debates over Green Belt planning permission, where the real issue is not whether new homes should be built but whether the current developer contribution system can fund the infrastructure to make them viable.

Instead of enabling strategic, balanced growth, CIL has created a framework where money is collected but not delivered, leaving both brownfield regeneration and potential Green Belt development equally constrained.

The result is a distorted housing market. Contributions intended to support density, walkability, and mixed-use neighbourhoods instead sit idle in council accounts. Developers are pushed towards what can be financed most easily, rather than what delivers the greatest long-term benefit for communities. Without reliable infrastructure funding, building new homes produces housing estates without the schools, transport, or health facilities they require.

Data from both the Federation of Master Builders and the House of Lords Built Environment Committee shows SME developers once delivered around 40% of new homes, but today that figure has collapsed to just 10%. Although large developers can spread CIL costs across portfolios or negotiate reductions, smaller firms, building ten homes rather than 1,000, face identical complexity without the same capacity to manage it.

This same structural imbalance extends into affordable housing. Councils frequently demand both maximum CIL contributions and 35-40% affordable housing quotas, a combination that only the biggest players can realistically manage. For everyone else, the maths simply does not add up - and when projects are forced to choose, it is the affordable units that disappear first. Research by the National Housing Federation shows delivery falls by 15-20% in areas after CIL adoption, proof that the levy system, as designed, undermines the very social outcomes it was meant to secure.

Consider what this means architecturally. Instead of mixed-tenure neighbourhoods that foster social integration, we get polarised development: luxury schemes that can absorb CIL costs, or large-scale affordable housing projects exempt from CIL but segregated from market housing. The Victorian ideal of the model village, where different social classes lived in proximity, became financially prohibited.

The system, supposedly designed to capture development value for communities, instead strips out the very elements (affordable homes, small-scale development, brownfield regeneration) that create sustainable places.

The contrast with international approaches reveals British exceptionalism at its worst. While the UK system is characterised by fragmentation, short-term thinking, and a lack of accountability, other countries have developed models that successfully integrate infrastructure delivery with urban development.

Dutch municipalities do not wait for developers to fund infrastructure through complex levy systems. They acquire land at agricultural value, install complete infrastructure, and then release serviced sites to the market. This approach, known as "active land policy," is not merely theoretical. The city of Almere, built on reclaimed polder land, now houses over 220,000 residents with comprehensive, pre-installed infrastructure. Schools open when families arrive. Transport operates from day one. Community facilities exist before the communities need them.

The financial model is transparent. Municipalities borrow against future land sales, with the value uplift between agricultural and serviced land funding the infrastructure. This allows developers to compete on the quality of their designs rather than their ability to game the planning system. It is a model of proactive, state-led urbanism that stands in stark contrast to the reactive, developer-led model prevalent in the UK.

This approach, known as 'actieve grondpolitiek,' exemplifies what Dutch planners call 'voorzieningen op voorhand' (provisions in advance). Dutch municipalities typically capture 30-40% of development value through this mechanism, compared to the 5-10% British councils achieve through CIL. The difference isn't just philosophical. In fact, it's mathematical.

Germany’s Baulandmodell (building land model) creates binding agreements where developers cover infrastructure costs, but municipalities face legal obligations for delivery within fixed timeframes.

The enforcement mechanism has teeth. German courts regularly order municipalities to refund contributions, plus interest and damages, when infrastructure does not materialise. This creates a level of accountability that is entirely absent from British practice. German municipalities employ the 'Städtebaulicher Vertrag' (urban development contract) model, embodying what planners term 'Planungssicherheit' (planning certainty), where all parties understand obligations and timelines from project inception.

Munich demonstrates the results, which include comprehensive, mixed-income developments with integrated public transport, community facilities, and green space, all delivered through single agreements rather than multiple, overlapping mechanisms. This approach recognises that infrastructure is not a cost to be minimized but a shared investment in the future of the city.

France’s Zone d’Aménagement Concerté (ZAC) system unifies what British planning fragments. The Clichy-Batignolles project in Paris, for example, delivered 7,500 homes, substantial commercial space, parks, metro connections, and a district heating system through one coordinated mechanism. The ZAC model treats infrastructure as what French planners call 'équipements publics structurants' (structuring public facilities), creating what anthropologist Marcel Mauss termed 'reciprocal obligation.

French mayors face legal responsibility for infrastructure delivery, which concentrates minds in ways that British council leaders never experience. The ZAC system provides a framework for long-term, strategic planning that can deliver complex, mixed-use developments in a coordinated and efficient manner.

These international examples demonstrate that there are viable alternatives to the UK’s broken system. So why does Britain persist with failure? They share a common thread: a recognition that infrastructure is a public good that requires proactive, strategic planning and a clear allocation of responsibilities.

The government's proposed Infrastructure Levy reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the problem.

According to the 2023 Levelling Up and Regeneration Bill, the new levy would replace CIL and Section 106 with a percentage-based charge on development value. Yet it maintains the same fatal flaw: councils collect, councils control deployment, and councils face no consequences for non-delivery.

As the British Property Federation warned in their consultation response, this amounts to "replacing one broken system with another." The Royal Town Planning Institute echoed these concerns, noting that changing the calculation method whilst preserving the institutional framework guarantees continued failure.

Think about what this means in practice. The proposal requires entirely new regulations, valuation methodologies, and administrative processes. The Planning Officers Society estimates a three to five year transition period. During this chaos, infrastructure delivery would effectively cease whilst councils retrain staff and developers navigate uncertainty.

The architectural profession sees this clearly. As the RIBA's policy response noted, the core issue isn't how levies are calculated but whether they translate into built infrastructure. A percentage-based levy that sits unspent is no improvement over a fixed charge that sits unspent.

Meanwhile, a technological revolution passes councils by entirely.

Consider what Amazon achieves: tracking millions of packages, optimising delivery routes in real-time, and predicting demand before it materialises. Now consider that most councils manage multimillion-pound infrastructure programmes using Excel spreadsheets and paper filing systems from the 1990s.

This isn't hyperbole. Freedom of Information requests to major councils reveal that fewer than 20% use integrated project management software for infrastructure delivery. Most lack basic GIS mapping of CIL obligations against infrastructure needs.

The solutions exist today. Machine learning algorithms could identify infrastructure stress points before failures occur. AI could optimise deployment sequencing to minimise disruption whilst maximising community benefit. Predictive analytics could forecast which investments generate the greatest social returns. Singapore's Urban Redevelopment Authority already uses such systems, reducing infrastructure delivery times by 30%.

But here's the deeper truth: technological competence requires organisational competence. Councils struggling with basic project administration won't suddenly excel at digital transformation.

What's particularly damning is that this technological paralysis is a choice. The same councils pleading technological poverty for infrastructure planning somehow manage sophisticated systems for parking enforcement and council tax collection. When revenue is at stake, digital capability mysteriously appears.

For example, Greenwich Council recently introduced camera-enforced road closures across multiple streets, complete with automatic number-plate recognition to churn out fines - proving they can deliver cutting-edge systems when it comes to penalising drivers, but not when it comes to upgrading the public realm or planning infrastructure.

We all need to admit that the real barrier isn't technology or cost. It's cultural. Modern systems would make infrastructure hoarding visible, deployment trackable, and failure accountable. That transparency threatens the current system's comfortable opacity.

After two decades observing this system’s failures, certain conclusions become inescapable.

The good news? The solutions aren't complicated.

The fundamental premise of CIL, that post-hoc taxation can deliver coordinated infrastructure, has been comprehensively disproven. Continuing to tinker with a failed concept wastes time and resources that we do not have.

The current system should be replaced with IDZs, where the state takes a leading role in land assembly and infrastructure delivery. Drawing inspiration from the Dutch model, the government should acquire land at existing use value, install the necessary infrastructure, and then release serviced plots to the market. The value uplift captured would fund the infrastructure, creating a self-sustaining system that ensures communities see the benefits of development before the disruption.

To introduce the accountability so clearly lacking in the current system, councils that collect infrastructure funds must be required to post bonds guaranteeing delivery within specified timeframes. Failure to deliver would trigger automatic compensation to the affected communities. This would create the kind of real-world consequences for non-delivery that are standard practice in Germany and other successful systems.

To ensure that infrastructure spending reflects local priorities, funds should be placed in community-owned trusts. This would give residents legal ownership of the funds, with councils proposing spending plans that communities would have the power to approve. This would shift power from remote bureaucracies to the people who actually live in and use the spaces being developed, creating a more democratic and responsive form of urbanism. Imagine actually having a say in how your community's money gets spent.

Instead of relying on upfront charges that stifle development, we should move towards a system of value capture through ongoing property taxation. When infrastructure genuinely improves an area, property values rise. A small, ongoing levy on this increased value would generate a continuous revenue stream for further investment, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement and aligning the long-term financial interests of the council with the well-being of the community.

The failure to deploy this £8 billion is not a passive act of administrative neglect; it is an active agent of national decline. The consequences ripple far beyond the boundaries of planning departments, creating a drag on UK productivity, exacerbating public health crises and social inequalities, and, most corrosively, dissolving the essential trust between citizens and the state.

Britain's productivity stagnation suddenly makes sense when mapped against infrastructure failures.

Start with the daily reality. Workers lose three hours to degraded commutes that promised transport improvements should have been eliminated. Parents, predominantly women, exit the workforce because childcare facilities never materialised. Business parks operate at half capacity without proper broadband or road access.

These aren't isolated inefficiencies. They're compounding factors on the entire economy. According to Centre for Cities research, inadequate infrastructure costs British cities £47 billion annually in lost productivity. That's six times the amount currently sitting unspent in council accounts.

The £8 billion itself represents frozen potential. Deployed strategically, it could eliminate these frictions and generate economic returns worth multiples of the initial investment. Instead, it sits idle whilst productivity flatlines.

The damage extends beyond economics into public health and social justice.

Consider the NHS paradox. Public Health England estimates physical inactivity costs the health service £7.4 billion annually. Yet councils hoard £873 million specifically designated for sports facilities and community spaces. We treat the symptoms whilst ignoring the cure sitting in council accounts.

The inequality mechanism is particularly cruel. Wealthy areas with existing infrastructure generate substantial CIL receipts they don't need. Poor areas desperately needing investment generate minimal CIL. Geographer David Harvey calls this "accumulation by dispossession": resources flowing from those who need them most to those who need them least.

Climate adaptation reveals similar dysfunction. Councils declare climate emergencies whilst banking funds designated for sustainable drainage, green infrastructure, and community energy projects. Some modelling suggests that each year of delayed or reduced investment in flood defences can increase damage costs by a nontrivial fraction - though the precise rate depends on local conditions and system age. The money to act exists. The will doesn't.

Most corrosively, this failure dissolves the social contract between citizens and state.

When councils repeatedly promise infrastructure, collect the funds, and then deliver little or nothing, public faith erodes. The latest Trust in Government survey from the Office for National Statistics shows that only one in three people (34%) say they trust local government—a figure that underlines how fragile legitimacy has become.

This creates a doom loop. Communities oppose all development, knowing disruption is guaranteed, whilst benefits rarely materialise. The very process of securing planning permission, once seen as a safeguard for communities, is increasingly viewed with suspicion as residents realise approvals rarely translate into the promised infrastructure.

Can you blame them?

Developers build to minimum standards, knowing quality won't affect their obligations. Councils focus on collection over delivery. The housing crisis deepens whilst the very mechanisms meant to make development acceptable instead make it toxic.

Political scientist Robert Putnam identified this as "declining social capital": when institutional failure erodes civic trust, collective action becomes impossible. Every unbuilt playground, every missing bus route, every absent health centre adds another crack to the foundation of local democracy.

The result?

A nation unable to build its future because it cannot trust its institutions to deliver. The £8 billion in unspent developer contributions sits in council accounts, a monument to institutional failure, whilst the country it could help transform slowly stagnates.

This failure must carry political consequences. Ministers announce reforms, councils slow-walk approvals, and developers navigate the chaos. Meanwhile, a generation is priced out of homeownership and no one accepts responsibility. Councillors presiding over £574 million in unallocated funds should face electoral judgement. MPs whose constituencies lack promised infrastructure must answer for it.

But accountability alone isn't enough. Change requires transparency, organisation, and pressure. Communities must audit council accounts, challenge developments without guaranteed infrastructure, and support only schemes with credible delivery. Your area's future is a political choice, not an inevitability.

Demanding accountability, however, is only half the equation. Political pressure without design quality delivers infrastructure badly. As a small architecture practice based in London with projects across the UK, we see what the numbers obscure: homes without infrastructure produce housing estates, not communities. Delivering real places requires high quality architectural services and solutions that integrate design, planning, and infrastructure from the outset. This integration shapes more than functionality. It builds the physical foundations of the community itself.

The mechanism is spatial. Thoughtful urban design creates the public realm where social cohesion forms: squares, parks, and streetscapes that transform strangers into neighbours. When architects and town planners design infrastructure alongside buildings, they ensure schools sit within walking distance, transport connects to employment, and community spaces anchor daily life.

This is why the £8 billion sitting in council accounts represents more than delayed projects. It represents schools unbuilt, transport delayed, and neighbourhoods incomplete. Unless political pressure forces change, the gap between promise and delivery becomes unbridgeable.

The choice is binary: transformation or managed decline. Which will your community demand?

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message