Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

You might have heard the rumours: gaining permission to build in England’s Green Belt is tough.

As a team with decades of experience in this space, we (unfortunately) can confirm that the rumours are true.

But wait!

Before you throw up your hands in defeat, there are some exceptions to the general rule of not permitting development in the Green Belt, and if your proposal meets one of these exceptions, then you may just be in luck.

In this article, we’ll uncover all the Green Belt exceptions and explore them in depth, allowing you to determine whether your proposal is possible, or if it’s nothing more than a pipe dream.

Let’s jump in.

Paragraphs 154 and 155 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) articulate that although local planning authorities (LPAs) should regard the construction of new buildings in the Green Belt as inappropriate, exceptions do exist.

By defining these exceptions, the planning policy acknowledges the practical need for certain types of development within the Green Belt and aims to strike a balance between the protection and pragmatic use of land.

Of course, developments falling under these exceptions must still demonstrate they do not harm the Green Belt's openness or conflict with its core purposes. This ensures that while limited development is allowed, the strategic function of Green Belts as a buffer against urban sprawl and a space for recreation and environmental preservation is maintained.

We’ve established the idea, now let’s run through the exceptions that might allow you to build in the Green Belt.

Let’s start off today’s blog with an overview of some of the newest exceptions, introduced in December 2024 in the updated NPPF.

If you weren’t aware, a new NPPF has been introduced, including some major changes to the Green Belt policy and to planning policy more broadly.

Why?

To speed up the planning system and get more homes built in Britain.

With this in mind, a few new key exceptions have been introduced to the updated NPPF in paragraph 155.

It reads as follows:

The development of homes, commercial and other development in the Green Belt should also not be regarded as inappropriate where:

a. The development would utilise Grey Belt land and would not fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt across the area of the plan;

b. There is a demonstrable unmet need for the type of development proposed;

c. The development would be in a sustainable location, with particular reference to paragraphs 110 and 115 of this Framework;

d. Where applicable the development proposed meets the ‘Golden Rules’ requirements set out in paragraphs 156-157 below.

In other words, if there is a need for the type of development (affordable housing, for example) and it’s in the right part of the Green Belt, then it might be deemed an exception.

What counts as the ‘right part’ of the Green Belt? If it’s in Grey Belt, land that is newly defined by the NPPF as:

“Land in the Green Belt comprising previously developed land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143. ‘Grey Belt’ excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.”

On a related note, the return of mandatory housing targets (a key part of the government’s planning reforms) will mean many areas will have a ‘demonstrable unmet need’ for housing.

Finally, for developments to be deemed an exception, they also need to adhere to three key Green Belt golden rules:

This update is significant, because it acknowledges that some Green Belt land (Grey Belt land) does not strongly serve Green Belt purposes and can be developed without fundamentally undermining the Green Belt’s role. This shift is a response to growing housing shortages, planning delays, and the need for a more nuanced approach that protects valuable Green Belt land while allowing sustainable development in appropriate locations.

Now the recent updates featured in the government’s planning reforms are covered, let’s review the exceptions that have been in place for a little longer.

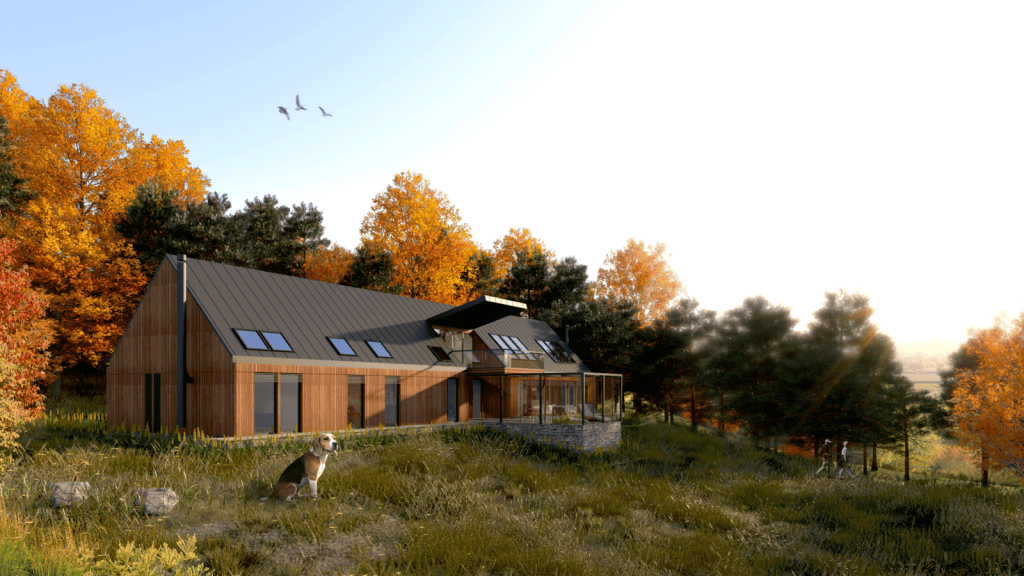

Paragraph 84 of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in England, previously known as Paragraph 80, outlines a specific exception to the general rule that the construction of new buildings in the Green Belt is inappropriate.

The exception of Paragraph 84 houses allows for the development of new buildings that are considered to be of exceptional quality. To qualify for this exception, the proposed development must meet the following criteria:

This exception is often referred to as the ‘Paragraph 80 house’ or ‘Paragraph 84 house’ and is intended to encourage the development of outstanding homes in the Green Belt and in other isolated rural areas.

A notable precedent of a Paragraph 84 exception in practice is the ‘Flint House’, designed by Skene Catling de la Peña architects and located in Buckinghamshire. This striking, angular home was granted planning permission in 2015 due to its innovative design and use of locally sourced materials, such as flint and chalk, which helped to integrate the building into its surrounding landscape.

The design of the building showcases several sustainable features, including a ground-source heat pump, rainwater harvesting, and high levels of insulation. Its unique design - which includes a series of cascading roof terraces and a sunken courtyard - was considered to significantly enhance its immediate setting and raise the standards of design in the area.

The approval of the Flint House demonstrates how Paragraph 84 can be used to encourage the development of exceptional homes in the Green Belt that push the boundaries of architecture. However, it's crucial to understand that the standards for qualifying under this exception are quite rigorous. Your proposal must clearly demonstrate that it is not only exceptional but that it is also sensitive to the character of its setting.

If your development is genuinely to support agriculture or forestry, then with the right design, you should be able to achieve planning permission in the Green Belt.

The definition of agriculture, as defined in section 336 of the Town and Planning Act 1990, includes a wide range of activities related to growing, farming, and breeding livestock, use of land for grazing, and use of land for the support of farming.

An example of a structure that would meet this exception includes stables and ancillary buildings for storage related to agricultural production or caring for livestock. Proposed agricultural buildings do not necessarily need to be used for commercial operations, as long as their use falls within the definition of agriculture.

An example of an approved agricultural development in the Green Belt was seen a few years ago at a farm in Warwickshire. In 2019, the farm owners sought permission to construct a new agricultural building to house cattle and store feed and machinery. The proposed development was located within the West Midlands Green Belt, which typically imposes strict restrictions on new construction.

However, the LPA recognised that the proposed building was essential for the operation of the farm and would support the long-term viability of the agricultural business. The design of the building was carefully considered to minimise its impact on the openness of the Green Belt, using materials and colours that blend well with the surrounding landscape.

In its decision to grant planning permission, the authority noted that the development met the criteria for agricultural buildings as an exception to Green Belt restrictions. The authority also acknowledged that the new building would contribute to the sustainable growth of the farm and would not result in any significant harm to the character or appearance of the countryside.

If the development you’re working on is designed for outdoor sports or recreation, or if it’s for a cemetery or burial grounds, the development may be considered appropriate so long as it doesn’t interfere with the openness of the Green Belt.

I know what you’re thinking - but isn’t any structure going to interfere with the openness of the Green Belt?

Well, this is part of the fun subjectivity of the Green Belt… often if there are structures on lands that aren't classified as ‘buildings’ - like a shed for example, then their replacement may be considered to not have an impact on the Green Belt’s openness.

Secondly, if it's just a sporting pitch or an equestrian riding arena you’re hoping to build, then because the mass of the structure is so minimal, it won’t impact the Green Belt’s openness.

A notable example of an outdoor recreational facility that was granted planning permission in the Green Belt is the case of a golf course development in Surrey. In 2017, a proposal was submitted to create a new 18-hole golf course, along with associated facilities such as a clubhouse, driving range, and parking areas on a site located within the London's Green Belt.

The developers argued that the proposed golf course would provide a valuable recreational amenity for the local community and would contribute to the area's sporting infrastructure. They emphasised that the design of the course and its associated buildings had been carefully considered to minimise their impact on the openness of the Green Belt. It was then concluded that the benefits of the development, in terms of enhancing local recreational facilities and promoting healthy lifestyles, outweighed any potential harm to the openness of the Green Belt.

The key consideration when applying this exception is that any extension or alteration must not result in a disproportionate addition to the original building. The term ‘disproportionate’ is not precisely defined in national planning policy, and its interpretation may vary between LPAs. However, as a general principle, an extension or alteration should not significantly increase the size of the original dwelling or have a substantial impact on the openness of the Green Belt.

To determine whether an extension or alteration is disproportionate, LPAs will typically consider factors such as the size, scale, and massing of the proposed development in relation to the original dwelling. They may also take into account the cumulative impact of previous extensions or alterations on the property.

As a general guideline, many LPAs consider extensions or alterations that increase the volume of the original dwelling by up to 30-40% to be acceptable under this exception. However, this is not a hard and fast rule and the specific criteria may vary between different local authorities. It is always advisable to consult with the relevant LPA and review their specific policies and guidance on extensions and alterations in the Green Belt.

A relevant example of an extension to an existing dwelling was one of our very own projects which wasn’t only in the Green Belt, but was also a listed building, in a conservation area, surrounded by protected trees. A challenge, to say the least.

The proposed extension involved the construction of a double-storey extension, which is notoriously difficult to achieve permission for on a listed building. While this extension would increase the overall footprint and volume of the original dwelling, the design of the extension was carefully considered to ensure that it would be in keeping with the character of the existing property and would not have a detrimental impact on the openness of the Green Belt.

The project involved significant collaboration with the LPA and conservation officers to ensure we produced a design that retained as much of the original building as possible. In assessing the application, the LPA referred to its specific policies on extensions and alterations in the Green Belt. They noted that the proposed extension would result in an increase in the volume of the original dwelling by approximately 35%, which was within the acceptable range as per their local guidelines.

In its decision to grant planning permission, the LPA emphasised that the design and materials of the proposed extensions needed to be sympathetic to the existing dwelling. Additionally, the LPA concluded that despite the extension's substantial size, it wouldn't result in disproportionately large additions compared to the original building. Consequently, it was considered to not adversely affect the Green Belt's openness.

The replacement of an existing dwelling is an exception that allows property owners to demolish an existing residential building within the Green Belt and replace it with a new dwelling, provided certain conditions are met.

This exception recognises that there may be circumstances where the replacement of an existing dwelling is preferable to its extension or alteration, such as when the original building is in poor condition, has an unsuitable layout, or fails to meet modern energy efficiency standards.

To qualify for this exception, the new dwelling must be in the same use as the original building it replaces. This means that a residential dwelling can only be replaced with another residential dwelling and not with a different type of building, such as a commercial or industrial structure. Additionally, the new dwelling must not be materially larger than the original dwelling it replaces.

Just like the previous exception, the new dwelling should not have a significantly greater impact on the openness of the Green Belt than the original building, and generally, new dwellings will be deemed appropriate so long as they are only 30-40% larger than the original. As noted above, this isn’t a strict rule and different LPAs will have different interpretations.

One of our recent projects utilised this exception for the construction of two three-bedroom houses on a Green Belt plot. As architects and planning consultants specialising in Green Belt projects, we secured permission for this development which significantly surpassed the maximum allowable 40% size increase over the original building. This case study shows that with patience, expertise, and creativity, even the most challenging Green Belt development projects can be successful.

This style of construction is usually accepted because it poses no further threat to the openness of the Green Belt. To be deemed acceptable, the development cannot have a materially greater impact than what currently exists and control needs to be exercised should there be any extensions incorporated in the project.

The building(s) need to be permanent and substantial and should not be a total conversion or major reconstruction. Additionally, the design needs to fit with its surroundings in terms of materials used and the building styles you’d typically see in the area.

A good example of this exception was the case of a former agricultural barn in the Green Belt of East Hampshire. In 2019, a proposal was submitted to convert the barn into a residential dwelling, making use of the existing structure and materials.

The barn was of permanent and substantial construction, having been built with solid brick walls and a slate roof. The proposed conversion involved minimal external alterations, with the addition of new windows and doors to make the building suitable for residential use.

The LPA assessed the application and determined that the proposed conversion would not have a materially greater impact on the openness of the Green Belt than the existing barn. They also noted that the design of the converted dwelling would be in keeping with the rural character of the area, using materials that were sympathetic to the surrounding landscape.

Limited infilling in villages is an exception that allows for the development of new buildings within existing settlements located in the Green Belt, provided that certain conditions are met.

But, what’s infilling?

In short, infilling refers to the development of small gaps or plots within the built-up area of a village, typically between existing buildings. The term ‘limited’ suggests that the scale and extent of infilling should be restricted and not result in a significant expansion of the village or harm to the Green Belt's openness.

Frustratingly, the precise definition of ‘limited infilling’ is not clearly outlined in national planning policy, which can lead to some ambiguity and varying interpretations between LPAs. This grey area can create challenges for both developers and local authorities in determining whether a proposed development falls within the scope of this exception.

Some LPAs may define limited infilling as the development of a small gap in an otherwise continuously built-up frontage, while others may consider it to include the development of a plot within the built-up area of a village, even if it does not directly adjoin existing buildings. The interpretation of ‘limited’ can also vary, with some authorities setting specific thresholds for the number of dwellings or the size of the plot that can be considered as limited infilling.

To illustrate this ambiguity, consider the case of a small village in the Green Belt of Cheshire, where a developer sought permission to build two detached houses on a plot of land between existing properties. The LPA initially refused the application, arguing that the development did not constitute limited infilling as it would result in a significant increase in the size of the village and therefore would harm the openness of the Green Belt.

The developer challenged the initial refusal, prompting a review by a planning inspector. The inspector considered the specific context of the village and the site in question, noting that the plot was located within the built-up area of the village and was surrounded by existing residential properties on three sides. The inspector also observed that the proposed development would not extend beyond the existing built-up area of the village and would not encroach into the surrounding countryside.

In their decision, the planning inspector concluded that the development of two houses on the plot could be considered as limited infilling, as it would not result in a significant expansion of the village or have a material impact on the openness of the Green Belt. The inspector emphasised that the interpretation of limited infilling should take into account the specific circumstances of each case, including the size of the village, the pattern of development, and the characteristics of the site.

As a result, the appeal was allowed and planning permission was granted for the construction of the two detached houses, subject to conditions ensuring that the development would be in keeping with the character of the village and would not have a detrimental impact on the Green Belt.

This example highlights the challenges and complexities involved in applying the limited infilling exception in practice and demonstrates the need for a careful balance between allowing for the sustainable growth of villages and protecting the openness and character of the Green Belt. It also underscores the importance of considering each case on its individual merits and taking into account the specific context and circumstances of the site and the surrounding area.

If affordable housing is urgently required and there are no other suitable locations to provide this type of housing within an area, then new, affordable homes can be deemed acceptable development in the Green Belt.

However, this exception is only applicable if policies are outlined in the area’s local plan that permits this development.

A relevant example of limited affordable housing for local community needs being applied as an exception can be found in the case of a development in the Green Belt of South Oxfordshire. In 2021, a housing association submitted a planning application to build a small-scale development of 12 affordable homes on a site adjacent to an existing village.

The LPA had identified a significant need for affordable housing in the area, with a shortage of suitable sites within the built-up areas of the district. The proposed development was specifically designed to meet the needs of local people, with a mix of rental and shared ownership properties that would be allocated to households with a strong local connection.

The authority considered the evidence presented by the housing association, which demonstrated a pressing need for affordable housing in the area and the lack of suitable alternative sites. They also noted that the proposed development was modest in scale and would be well-integrated with the existing village, with no significant impact on the openness of the Green Belt.

Expectedly, to qualify for this exception, the proposed redevelopment must not have a greater impact on the openness of the Green Belt than the existing development. This means that the new development should not exceed the height, volume, or footprint of the existing structures on the site. LPAs will assess the impact of the proposed redevelopment on the Green Belt's openness, taking into account factors such as the site's location, the surrounding landscape, and the scale and design of the new development.

When applying the previously developed land exception, developers should carefully assess the site's planning history and the nature of the existing structures, ensuring that the proposed redevelopment meets the necessary criteria and does not have a greater impact on an area's openness than the existing structures.

A notable example of this exception being applied can be found in the case of a former industrial site in the Green Belt of Hertfordshire. In 2019, a developer submitted a planning application to redevelop the site, which had previously been used for manufacturing and storage purposes, into a mixed-use development comprising residential units and commercial space.

In assessing the application, the LPA considered the impact of the proposed redevelopment on the openness of the Green Belt. It noted that the existing industrial buildings were substantial in scale and had a significant impact on the area's openness. The proposed development, while introducing new buildings, was designed to be more compact and visually appealing, with a reduced overall footprint compared to the existing structures.

The authority also took into account the site's location, which was adjacent to an existing settlement and well-connected to local services and infrastructure. It considered that the redevelopment of the previously developed land would contribute to the sustainable growth of the area and would not have a greater impact on the Green Belt's openness than the existing development. As a result, planning permission was granted for the redevelopment of the site.

Despite what you may assume, mineral extraction is not necessarily incompatible with the Green Belt’s purposes and is therefore listed as one of the few exceptions. This is because minerals of course can only be extracted from where they naturally occur.

Further, mineral extraction is typically a temporary operation, allowing the Green Belt to be restored to its former condition once the process is complete.

A notable example of mineral extraction that was granted planning permission in the Green Belt was the case of a sand and gravel quarry in Buckinghamshire. The mining company argued in their planning application that the mineral extraction was necessary to meet the local and regional demand for construction materials. The company proposed a comprehensive restoration plan, which would see the site progressively restored to a mix of agricultural land, woodland, and wetland habitats once the mineral extraction was complete.

The LPA had to think carefully and weigh the need for mineral extraction against the potential impact on the Green Belt. Ultimately, they concluded that while the proposed quarry would have a temporary impact on the openness of the Green Belt, the mineral extraction was a necessary and important activity that could only take place where the resources were found. The long-term benefits of the site's restoration and the contribution to meeting the area's mineral needs therefore outweighed any temporary damage.

In these cases, the development needs to demonstrate that it both preserves and enhances green infrastructure throughout its duration, plus a comprehensive restoration plan promising the site's gradual return to a blend of agricultural, woodland, and wetland habitats post-extraction will need to be provided.

The development of local transport infrastructure can be considered an acceptable exception within the Green Belt when it’s necessary to support the residents of a township or community located in or near the Green Belt. This exception recognises the importance of providing adequate transportation links to ensure the sustainability and wellbeing of these communities.

Local transport infrastructure can encompass a range of projects, such as the construction of new roads, the improvement of existing highways, the creation of public transport hubs, or the development of cycling and pedestrian networks. These infrastructure projects aim to enhance connectivity, reduce congestion, and improve access to essential services and amenities for residents living in or near the Green Belt.

One example of local transport infrastructure being permitted in the Green Belt is the A57 Link Roads project which includes the construction of two new routes to enhance connectivity. The project introduces a dual carriageway connecting the M67 to the A57(T) at Mottram Moor and a single carriageway linking the A57(T) at Mottram Moor with the A57 at Woolley Bridge, significantly improving the area's transport infrastructure.

Of course, getting a project of this scale over the line needed to be done carefully, focusing on minimising the impact on the openness of the Green Belt, with landscaping and screening measures incorporated to reduce visual intrusion. These types of proposals should also include the creation of new wildlife habitats and the enhancement of existing green spaces, to show how local transport infrastructure can be sensitively integrated into the Green Belt environment.

Community Right to Build Orders are documents that, if supported in a local referendum, allow small development to proceed without going through the hassle of the normal planning application process. Types of development might include shops, businesses, community facilities, and affordable housing.

Similarly, Neighbourhood Development Orders allow communities to gather and create general planning policies for the use of land and development in their locality. This then becomes a part of the neighbourhood’s local plan and can help to inform what kinds of developments are built in the area.

The types of developments these orders can allow include:

These orders empower local communities to shape the development in their area, while still respecting the overall goals of the Green Belt.

A good example of a Community Right to Build Order being used in the Green Belt can be found in the case of a small village in the Green Belt of Wiltshire. In 2018, the local community came together to propose the development of a new community hall and a small number of affordable homes for local people on a site within the village.

The community prepared a detailed proposal, which included plans for a modestly sized community hall and six affordable homes, designed to meet the specific needs of the village. The proposal was put to a local referendum, where it received overwhelming support from the local community.

As the proposed development was supported through a Community Right to Build Order, it was able to proceed without the need for a separate planning application. The LPA reviewed the proposal to ensure that it was in line with the overall objectives of the Green Belt and that it would not have a detrimental impact on the area's openness and character.

The authority noted that the proposed development was small-scale and would provide much-needed community facilities and affordable housing for local people. They also considered that the development would be well-integrated with the existing village and would not have a significant impact on the Green Belt's openness.

There you have it; a comprehensive rundown of every exception, which we hope has provided you with much more clarity when it comes to how you can potentially gain permission for your Green Belt development.

What if none of these exceptions seem relevant to your case?

Don’t give up the dream just yet.

Alongside the 12 exceptions that allow for building to go ahead in the Green Belt, we’ve also identified 13 very special circumstances that could very well suit your project brief.

To help you establish a well-rounded sense of exactly what these circumstances are, we’ve penned a detailed article on Green Belt very special circumstances which we hope holds the key you need to unlock your planning permission endeavours.

As we think you would have gathered by now, building in the Green Belt is not always an easy pursuit. However, if you meet one of the exceptions and work with experienced Green Belt architects and planning consultants, you could greatly increase your chances of obtaining planning permission for your project in the Green Belt

While ultimately there’s no guarantee of gaining planning permission to build on the Green Belt, there’s one thing we are certain of: if you choose to work with an expert team rather than attempting this mountainous task on your own, you’ll be placing yourself in a much better position for achieving success.

If you’d like to work with our multidisciplinary team of architects and planners who boast decades of experience in green belt projects, then please don’t hesitate to get in touch. Our expertise in navigating the complexities of UK planning policy equips us to maximise our clients' chances of securing planning permission for their Green Belt projects.

The Green Belt is one of the most contentious and misunderstood pieces of planning policy in England and it’s a topic we at Urbanist Architecture have a lot of experience working with. For this reason, we decided to pool our learnings and pen a book delving deep into the Green Belt from every possible angle.

‘Green Light to Green Belt Developments’ investigates the policy's biggest winners and losers, and explores its connections to climate change and the housing crisis, as well as what the future might hold, particularly now a new Labour government is in power. It also looks at the history of the policy and how it’s managed to endure while other policies have evolved and adapted with the times. Of course, it also identifies the exceptions and circumstances that exist for permitting development in the Green Belt, so you can better your chances of gaining planning permission.

We’ve written this book for anyone seeking a more rounded understanding of one of England's most debated urban planning issues, making it accessible to both industry professionals and the general public.

Whether you are a landowner in the Green Belt wishing to understand the potential for land value uplift or a developer planning to build new homes in the Green Belt, this book is an essential read. Order your copy now.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message