Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Stand on a bridleway where Birmingham dissolves into Worcestershire and pause.

What strikes you first isn't the birdsong or the scent of wild grass - it's the breathing room. Sky vaults overhead, hedges crouch low, horizons stretch endlessly. This quality, this freedom from urban containment, is what planning law calls “openness of the Green Belt.”

Together with permanence, openness forms the philosophical cornerstone protecting 1.6 million hectares of English countryside from the relentless march of suburbia. Yet for all its importance, openness remains a maddeningly elusive concept - a principle everyone cites but few truly master.

Here's the paradox that keeps developers awake at night and leaves landowners perplexed: why might a modest agricultural shed fatally compromise openness, while a 40-hectare solar array is deemed to enhance it? Such outcomes reveal a sophisticated interplay between policy, perception, and professional judgment that defines contemporary practice.

The landscape has shifted seismically.

The High Court's rigid, volumetric approach in Timmins (2014) gave way to the Court of Appeal's revolutionary Turner decision (2016), which insisted openness has both spatial and visual dimensions.

The Supreme Court's Samuel Smith ruling (2020) then cemented this, declaring openness a “broad planning judgment” rather than a calculator-led test.

Now, with the December 2024 National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) introducing “Grey Belt” land and the February 2025 planning practice guidance (PPG) clarifying the new Green Belt rules, we are witnessing the most significant evolution in Green Belt policy for a generation.

Before we go any further, here’s a short clip from my Sky News Live interview. It captures the practical reality behind today’s Green Belt debate: why the term is often misunderstood, what the Grey Belt reforms are trying to achieve, and why schemes refused locally on perception grounds are often allowed on appeal when the evidence and policy are applied as intended.

With that context, the core point is simple. Green Belt policy is not a blanket ban on change, and “openness” is not a proxy for “this feels like countryside”. The real test is evidence-led and policy-led: whether land is performing strongly against the Green Belt purposes, and whether development would preserve openness in its spatial and visual sense — or, in Grey Belt cases, whether the proposal qualifies as not inappropriate development under the paragraph 155 gateway.

Crucially, Mole Valley District Council v Secretary of State (2025) locks the sequencing into place: where development meets the Framework’s “not inappropriate” gateways, openness is not a separate, free-standing objection to be re-run afterwards.

That direction is now echoed in the draft NPPF 2025, which restates the “not inappropriate” routes more explicitly, including previously developed land in the Green Belt where there would be no substantial harm to openness, and Grey Belt development that would not fundamentally undermine the remaining Green Belt’s purposes across the plan area.

If you are a landowner wondering why your neighbour's scheme sailed through while your barn conversion failed, or an architect whose elegant design for a Paragraph 84 house was crushed by outdated volumetric calculations, this guide is your blueprint for understanding - and winning - the openness argument.

This comprehensive guide maps every contour of this evolving landscape. We will:

By the time we're through, your perspective on Green Belt openness will have evolved from outdated calculations to a sophisticated grasp of modern planning judgement, ready to confidently balance the crucial spatial and visual aspects that define today’s arguments for Green Belt developments.

Navigating policy to achieve planning permission in the Green Belt requires precision. Understanding the hierarchy of planning law and policy is the first step to building a compelling case.

Under section 38(6) of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, planning decisions must be made in accordance with the development plan "unless material considerations indicate otherwise."

Since local development plans invariably drape Green Belt land in highly protective policies, the challenge for applicants is almost always to demonstrate that national policy - specifically the NPPF - or other compelling factors provide a justification to override that restrictive local starting point.

Think of it as a high-stakes chess match where the local plan holds the opening advantage. Your countermove is to deploy the NPPF's exceptions and the new Grey Belt provisions with surgical precision.

Chapter 13 of the NPPF distills Green Belt protection into 19 carefully crafted paragraphs.

For assessing openness, these are the ones that matter most:

Updated on 25 February 2025, the PPG crystallises decades of case law into a practical assessment framework. It confirms that when assessing the impact on openness, decision-makers can and should consider:

These four bullets have transformed abstract legal theory into a practical methodology now embedded in officer reports and appeal decisions across the country.

Crucially, the PPG now clarifies the Mole Valley principle: "If development is considered to be not inappropriate development on previously developed land or grey belt, then this is excluded from the policy requirement to give substantial weight to any harm to the Green Belt, including to its openness." This exclusion applies equally to previously developed land (PDL) redevelopment under paragraph 154 (where the substantial harm test is met) and Grey Belt development under paragraph 155, fundamentally altering the assessment framework for both categories.

The guidance confirms that "where development is not considered to be inappropriate in the Green Belt, it follows that the test of impacts to openness or to Green Belt purposes are addressed and that therefore a proposal does not have to be justified by 'very special circumstances'."

This represents a fundamental shift from the traditional approach where every development was scrutinised for openness impact, to a policy-led framework where appropriateness determines the analytical approach.

The PPG (paragraph 64-001) provides the all-important definition: Grey Belt land is a parcel of Green Belt land that does not make a "strong contribution" to at least three of the five Green Belt purposes. The guidance specifically points to purposes (a) sprawl prevention, (b) merger prevention, and (d) historic setting preservation as the key considerations.

Development on these sites must then pass the tests in NPPF paragraph 155 and must not "fundamentally undermine" the purposes of the remaining Green Belt across the plan area. Early Grey Belt appeal examples are already showing that this creates a different, more nuanced balancing exercise than the traditional, hard-line approach.

Purpose assessment has become site-specific, with inspectors conducting detailed analysis of how individual sites contribute to the five Green Belt purposes rather than applying blanket assumptions. The "strong contribution" test has proved more nuanced than initially anticipated, as sites can fail to make a strong contribution to purposes even if they provide some benefit, provided this doesn't reach the "strong" threshold.

In practice, inspectors are now examining each site individually to see how it serves the Green Belt purposes, rather than making general assumptions. The "strong contribution" test is proving quite flexible - sites can fail this test even if they provide some Green Belt benefits, as long as those benefits aren't particularly strong.

Furthermore, planning inspectors are taking a practical approach to the Golden Rules, especially when it comes to affordable housing requirements for smaller developments. Most significantly, the "fundamental undermining" test sets a higher bar than the old "any harm" standard. Instead of just looking at immediate site impacts, inspectors now consider whether development would damage the Green Belt's strategic role across the entire planning area.

The concept of openness has been forged in the courts. Understanding this evolution is not just an academic exercise; it provides the intellectual firepower to justify a planning judgment. Inspectors reflexively cite these cases - so should you.

In what now seems like a distant era, the High Court ruled that visual impact was irrelevant when gauging openness. Green J declared it "wrong in principle to arrive at a specific conclusion as to openness by reference to visual impact." This led many local planning authorities to rely on mechanistic, cubic-metre maths alone, ignoring design quality, landscape context, or the actual lived experience of the space.

The Court of Appeal confirmed that buildings for agriculture and forestry are deemed "appropriate" development by policy and therefore, in principle, cannot be harmful to openness. The judgment separated the black-and-white policy definition from the on-the-ground experience, with Lindblom LJ clarifying: "The concept of 'openness' here means the state of being free from built development, the absence of buildings - as distinct from the absence of visual impact."

This was the ruling that changed everything. Sales LJ, in a landmark Court of Appeal judgment, declared that openness is an “open-textured” concept that goes far beyond simple maths. He established two critical limbs for its assessment:

His memorable phrase - that Green Belts exist so "the eye and the spirit should be relieved from the prospect of unrelenting urban sprawl" - eloquently shifted the focus from arithmetic to human experience.

The Supreme Court provided the final word, endorsing Turner while refining its application. Lord Carnwath established three key principles:

This ruling empowers decision-makers, giving them the latitude to weigh the different aspects of openness based on the evidence before them, rather than slavishly following a rigid formula.

In a crucial clarification for cases where harm is found, the Court of Appeal confirmed that when conducting the very special circumstances (VSC) balancing act, all harm - Green Belt harm (including to openness) and any "other harm" (e.g., to landscape character, highways, or amenity) - must be placed on the negative side of the ledger. This ensures intellectual honesty in the final planning balance.

The High Court's judgment in Mole Valley represents the most significant clarification of Green Belt openness law since Turner. The case arose from a challenge to an Inspector's decision to grant planning permission for gypsy and traveller pitches on Green Belt land, where the council had refused permission citing "visual and spatial impact on Green Belt openness."

Mr Justice Choudhury definitively resolved a fundamental question that had been troubling practitioners: whether openness can be assessed as a separate consideration for development that qualifies as 'not inappropriate' under the NPPF.

The Court's definitive ruling transforms Grey Belt practice from complex assessment to binary policy compliance. Once development meets the paragraph 155 tests, any openness-based refusal would constitute a legal error, not merely poor planning judgment.

This creates two distinct pathways for Green Belt development: the traditional route with its complex openness requirements, or the Grey Belt route where such assessment becomes legally irrelevant. For practitioners, Mole Valley eliminates the uncertainty that has plagued Green Belt applications—the question is no longer "will this harm openness?" but simply "does this qualify under paragraph 155?"

Local authorities can no longer rely on subjective openness concerns to refuse qualifying Grey Belt development. Such an approach would be legally unsound and vulnerable to successful challenge. In other words, the judgment clarifies the Green Belt is an urban-containment policy, and 'openness' is not the same as 'character'. Once development is appropriate, there is no definitional Green Belt harm.

These cases are now the reflexive language of inspectors, but the Mole Valley judgment has fundamentally altered their application. As we will see, Inspector K Townend's Upper Austby Farm decision explicitly cites Turner for its spatial and visual limbs and Samuel Smith to justify her holistic judgment, concluding that a new, well-designed bungalow improves perceived openness compared to eight lawful shipping containers.

Viewed through the lens of the Mole Valley judgment, Inspector Townend's approach in Upper Austby becomes even more significant. While the proposal was technically "inappropriate development" (and therefore subject to openness assessment), the Inspector's methodology demonstrates the sophisticated judgment that Turner and Samuel Smith enable.

Had the Upper Austby proposal qualified as Grey Belt development under paragraph 155, the Mole Valley precedent suggests that the detailed openness assessment would have been unnecessary – the policy determination of appropriateness would have resolved the openness question as a matter of law.

This highlights the strategic importance of the Grey Belt route: it transforms complex, subjective openness debates into straightforward policy compliance exercises.

So, how do you translate these legal principles and policy bullets into a robust, evidence-based assessment? The PPG’s four-bullet test can be expanded into a practical, five-dimension model that covers every angle.

Important note: This framework applies to development that requires openness assessment. For Grey Belt development qualifying under paragraph 155, and previously developed land (PDL) development meeting the paragraph 154 tests, the Mole Valley precedent establishes that such detailed assessment is legally unnecessary – the policy determination of appropriateness resolves the openness question as a matter of law.

This is the quantitative core of the assessment, addressing the physical presence of development.

This addresses the Turner visual limb - what people will actually see and experience.

This captures the PPG's "degree of activity" bullet, recognising that openness is also about tranquillity.

This dimension considers the permanence of the impact.

Linked to duration, this assesses whether the land can realistically be returned to an open state.

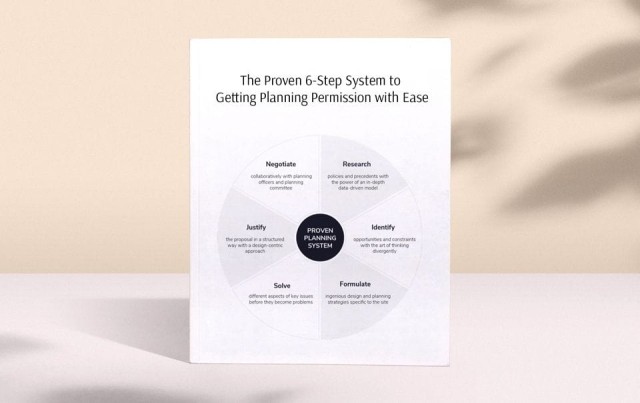

A winning openness case is built on a foundation of irrefutable evidence, woven into a compelling narrative. Our advice? Follow this six-step process:

Establish the lawful planning position comprehensively. This is your factual starting point. Don't just assess the empty field; assess what could lawfully be there.

Run the numbers. Calculate and compare the existing versus proposed footprints, volumes, and heights. Critically, map the pattern of development to show how a proposal might consolidate a scattered, messy site into a tight, coherent form.

Move from numbers to perception. Select representative public viewpoints and produce accurate, verifiable photomontages. Never forget to consider seasonal changes and the cumulative impact alongside other developments.

Quantify the change in human presence. Compare current and proposed vehicle movements and operational characteristics. For temporary schemes, detail the permission length, restoration methodology, and financial guarantees.

This is where analysis becomes advocacy. Weave the evidence from the five dimensions into two or three tight, plain-English paragraphs. Link the numbers to the lived experience. For example, connect a reduction in footprint (spatial) to the opening up of a key view (visual).

Inspector Townend’s July 2025 decision is the perfect template. The Inspector noted the proposal was technically "inappropriate" but then concluded: "The proposal would result in the removal of the existing containers and other units. This would be beneficial to both the spatial and visual aspect of openness." This demonstrates a holistic judgment where a clear visual and spatial improvement outweighed a definitional policy breach.

The principles of openness apply universally, but their emphasis shifts depending on the type of development.

Under paragraph 154(g), previously developed land (PDL) redevelopment is not inappropriate, provided it does not have a greater impact on openness. The bar is high, but the path is clear.

Post-Lee Valley, new buildings for agriculture are appropriate by definition. However, this is not a free pass.

Solar farms and wind turbines are often controversial. Their success on openness grounds leans heavily on the final two dimensions of our model.

This appeal decision is a masterclass in contemporary openness assessment. The Inspector, K Townend, allowed a new bungalow on the basis that it improved openness compared to the lawful baseline of eight large shipping containers.

|

Inspector Townend’s Finding |

Practitioner’s Notes |

|

A lawful development certificate confirmed the right to site eight shipping containers (Use Class B8) on the land. |

The baseline is the ugly reality, not a pristine field. This is the crucial starting point for the comparison. |

|

The proposed new bungalow is defined as "inappropriate development" in the Green Belt. However, it results in a footprint reduction of 730m². |

The spatial ledger starts with a massive credit. The definitional harm is acknowledged but immediately countered by a tangible spatial benefit. |

|

The new building's mass "reads as a coherent rural building," whereas the lawful containers would inject an "industrial character and colour." |

Visual perception trumps abstract numbers. A slightly taller but well-designed building is judged visually preferable to lower, scattered industrial clutter. |

|

Activity levels would fall significantly. Lawful HGV movements for the container business would vanish, replaced by minor domestic traffic. |

The PPG’s activity bullet is explicitly addressed and scores as a major positive for the proposal. |

|

The definitional harm was outweighed by the substantial benefits, including the significant improvement to openness. Very special circumstances were found. |

The Redhill ledger in action. All benefits were weighed against the harm, and the benefits clearly won. |

Inspector Townend’s reasoning directly mirrors Turner ("spatial and visual aspects") and cites Samuel Smith to justify making a holistic, evidence-based planning judgment. This decision is now a powerful precedent for schemes that swap lawful, unsightly clutter for high-quality, consolidated design.

The introduction of Grey Belt land in the 2024 NPPF is the most significant strategic shift in Green Belt policy in decades. It creates a new pathway for development that avoids the high bar of very special circumstances.

The route via NPPF paragraph 155 requires satisfying four cumulative tests:

If a scheme passes these gateways, it is not inappropriate development. The crucial consequence, confirmed in Footnote 55, is that the automatic "substantial weight" against the proposal is removed. The assessment becomes a standard planning balance under section 38(6).

This policy shift creates a two-tier system for assessing openness. The key question for a Grey Belt site is not whether there is any harm to openness, but whether the harm is so significant that it "fundamentally undermines" the purpose of the remaining Green Belt in the area.

| Traditional Green Belt Assessment | Grey Belt Assessment |

| Starting presumption: "Substantial weight" given to any harm to openness (NPPF p153). | Starting presumption: No automatic substantial weight against harm if gateway tests are met (NPPF p155, fn 55). |

| Balancing test: Benefits must "clearly outweigh" the harm (very special circumstances). | Balancing test: A standard planning balance under s.38(6) of the 1990 Act. |

| Focus of report: Proving VSC to overcome harm to openness. | Focus of report: Showing that any harm to openness does not cross the "fundamental undermining" threshold, and highlighting scheme benefits. |

Here’s how we have applied this framework to one of our Grey Belt projects at Urbanist Architecture.

|

Dimension |

Assessment |

|---|---|

| Spatial |

Existing: 100% hard surface cover. Height of 0m (excluding parked vehicles). Proposed: 42% building/hardstanding cover. 8.2m ridge height, consolidated centrally. Net Position & Justification: Positive – Spread shrinks dramatically. Height is introduced, but its impact is limited by tight, consolidated massing. |

| Visual |

Existing: Glare from tarmac. Cluttered views of parked vans from a public right of way. Proposed: High-quality brick and slate design echoing the village vernacular. A new 3m landscape buffer frames views over the new park to the fields beyond Net Position & Justification: Strongly positive – The visual experience is transformed from derelict clutter to a curated, landscaped edge. |

| Activity |

Existing: Peak of 60 vehicle movements on a Saturday. Proposed: Estimated 45 daily trips, managed through a private home-zone. Net Position & Justification: Positive – A slight fall in total movements, with the noise profile becoming less episodic and intrusive. |

| Duration |

Existing: Permanent hard-surfacing. Proposed: Permanent dwellings. Net Position & Justification: Neutral. |

| Remediability |

Existing: Tarmac could be removed. Proposed: Houses are permanent. Net Position & Justification: Minor negative – This is the trade-off, but it's mitigated by the permanent public benefit of the new open space. |

"[...] The legal framework for openness operates at two levels: first, the methodology for assessing openness when assessment is required, and second, the circumstances in which such an assessment forms part of the decision-making process. The established case law provides clarity on both levels.

Turner v SSCLG [2016] EWCA Civ 466 confirmed that openness comprises spatial and visual dimensions, supported by the principle that Green Belts exist to provide relief from unrelenting urbanisation.

Samuel Smith Old Brewery v North Yorkshire CC [2020] UKSC 3 reaffirmed that openness is a matter of planning judgement rather than a rigid formula, allowing decision-makers to consider design quality, landscaping and cumulative effects.

Most significantly, the High Court’s decision in Mole Valley District Council v Secretary of State [2025] EWHC 2127 (Admin) clarified the relationship between openness and appropriateness under the NPPF (December 2024). The Court confirmed that where a proposal satisfies paragraph 155 and is therefore not inappropriate development, there is no separate or residual requirement to undertake a harm-based openness assessment. The preservation of openness is inherent within the policy classification of “not inappropriate”, and decision-makers should not reintroduce a harm test once the gateway tests are met.

This clarification establishes that the central question for proposals on Grey Belt land is whether the paragraph 155 criteria are satisfied. As demonstrated in this submission, all three gateway tests are met. Accordingly, the proposal must be treated as not inappropriate development for the purposes of the NPPF (December 2024). Within this policy framework, there is no requirement for a standalone assessment of harm to openness.

While the pre-application response focused on perceived harm to openness, this was based on the superseded NPPF 2023 and the traditional two-stage approach that applied at that time. The updated policy position and case law now provide a clearer and more structured framework for the assessment of Grey Belt sites. The analysis presented in this report reflects that updated position, supported by the full spatial, visual and functional evidence now submitted. [...]"

"[...] The spatial dimension of openness relates to the extent of built form on the site. The proposal achieves a significant enhancement to spatial openness by reducing the overall site coverage and consolidating the built footprint. The existing tarmac-dominated arrangement is replaced with a more efficient layout, which substantially increases the amount of soft landscaping. The attached table provides a quantitative comparison of the existing and proposed conditions

This 16.79% reduction in hard surfacing represents a fundamental improvement in spatial openness. The proposed courtyard layout strategically consolidates the built form into the northern portion of the site, which facilitates the restoration of a large, permeable landscape area to the south. This approach reduces the perception of sprawl and enhances the definition of open space across the site.

The visual dimension of openness concerns the impact of the development on views across the site. The proposal delivers a marked improvement in visual openness by replacing the industrial character of the existing car park with high-quality vernacular architecture and extensive new planting.

From the primary public viewpoint at Public Right of Way HP19/4, the harsh and visually intrusive tarmac surface is replaced by a context-sensitive residential scheme. The use of a vernacular materials palette, including local brick, clay tiles, and timber, ensures the new buildings integrate harmoniously with the village character. The scale of the development is sympathetic to the rural setting, and the introduction of a publicly accessible pocket park provides a positive visual focus and a significant landscape enhancement. The attached table summarises the key visual improvements.

In conclusion, the proposal transforms the site from a visually intrusive and spatially compromised condition to one that is defined by high-quality design and a significant increase in landscaped, open space. This results in a clear and demonstrable enhancement of both the spatial and visual dimensions of Green Belt openness. [...]"

Before finalising any Green Belt planning application, it is vital to test the robustness of your case on Green Belt openness. This final review translates the complex principles of planning judgement, as required by the Supreme Court in Samuel Smith, into a practical acid test.

The following checklist distills the entire assessment framework, from quantifying the spatial and visual aspects of openness to evidencing how you are enhancing openness, into five critical questions.

A confident 'yes' to each is the hallmark of a defensible submission, ready to withstand scrutiny and effectively counter claims of harm to openness, whether you are arguing for very special circumstances or proceeding under the Grey Belt land policy.

The trajectory of recent case law points towards one clear conclusion, a principle that directly shapes our work as Green Belt architects and planning consultants: A demonstrable improvement to the visual and spatial aspects of openness now carries more weight than rigid, outdated assessments.

A robust case, as confirmed by the checklist, answers the technical questions of impact; high-quality design then addresses the qualitative experience. It is the primary tool for mitigating any residual visual harm and for delivering the tangible betterment that can transform a defensible planning application into a truly compelling one.

Excellent design cannot make an inappropriate scheme appropriate, but it can be the decisive factor in borderline cases by mitigating harm and delivering tangible betterment.

| Pitfall | Symptom and Remedy |

|---|---|

| Applying the wrong test |

Symptom: Arguing "very special circumstances" on a Grey Belt site, or vice-versa. Remedy: Use the correct terminology. For Grey Belt, state that the scheme "would not fundamentally undermine openness" and reference NPPF footnote 55. |

| Ignoring the baseline |

Symptom: Comparing your proposal to a green field when the site has a lawful use for something ugly, like scrap storage. Remedy: Establish the lawful baseline with a certificate first. Frame your proposal as an improvement on that baseline, not the idealised field. |

| The "landscaping will fix it" fallacy |

Symptom: Proposing a huge building and assuming a dense screen of trees will make the spatial harm disappear. Remedy: Be honest. Landscaping can soften visual impact, but it cannot mitigate spatial harm. Acknowledge the spatial impact and focus on how you have minimised it through careful siting and massing. |

The landscape of Green Belt openness has been transformed beyond recognition. From the rigid volumetrics of Timmins through the dual-dimension framework of Turner to the policy primacy established in Mole Valley, we have witnessed a complete evolution in legal thinking.

The introduction of Grey Belt provisions creates an alternative pathway that bypasses traditional openness assessment entirely. For qualifying sites, the complex spatial and visual analysis that has dominated Green Belt practice becomes legally irrelevant – replaced by straightforward policy compliance tests.

This represents both opportunity and challenge. Practitioners who master the Grey Belt framework can deliver development that would have been impossible under the traditional approach. But those who continue to apply outdated methodologies risk missing the strategic advantages that the new framework provides.

The five-dimension assessment model remains crucial for traditional Green Belt applications, but the Mole Valley precedent demands that we first ask the fundamental question: is this development 'not inappropriate' under paragraph 155? If the answer is yes, the openness debate is over before it begins.

For landowners, architects, and planning professionals, this new paradigm offers unprecedented opportunities to deliver sustainable development in Green Belt locations. The key is understanding which analytical pathway applies to your specific proposal and deploying the appropriate methodology with precision and confidence.

The paradox of Green Belt openness has been resolved: it's not about complex calculations or subjective judgments, but about understanding the policy framework and applying it correctly. Master this distinction, and you master the modern Green Belt.

We believe that it is in the nature of things that many hard problems are best solved when they are addressed backward. While the concept of inversion has been applied mostly to mathematics, the model is one of the most powerful in our toolkit for formulating planning and design strategies for complex planning cases.

That’s why, when we take on a Green Belt project, we begin by drafting the refusal letter we never want to receive. Setting out every policy reason the scheme could be turned down — loss of openness, landscape harm, inadequate very special circumstances — exposes the exact places where the design must work hardest.

Each identified risk then directs a design response: volumes are set low to preserve baselines, building lines follow existing hedgerows, habitat corridors are drawn first and architecture follows, and transport measures are woven into the site layout rather than appended later.

By the time the application is submitted, objections have been pre-empted, consultees are onside, and the determination often feels inevitable. And, if it goes to appeal, our evidence is already written.

If you believe your project would benefit from an inversion-led, design-first approach built to satisfy policy tests upfront, we’d be glad to discuss how we can help.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message