Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The government recently finalised its big plans for the Green Belt in an updated NPPF, including an official ‘Grey Belt’ definition and compulsory reviews of Green Belt land boundaries when required.

Given just how contentious Green Belt reform is, there has been some inevitable backlash. However, much of this opposition seems to stem from the many myths and misconceptions that have forever surrounded this policy.

With this in mind, we thought we’d strip things back to basics and break down the Green Belt, including its five core purposes and how those purposes are assessed when it comes to classing land as Green Belt.

Here we go.

Green Belt land in the UK is a designated area of open space around cities and towns, primarily aimed at controlling urban growth and preventing urban sprawl.

The concept was introduced as part of the UK’s planning system under the Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 and ensures Green Belt land remains largely undeveloped, maintaining a clear distinction between urban and rural areas and preserving the openness of the landscape.

The NPPF identifies openness as an 'essential characteristic' of Green Belts, the policy referring not only to the absence of buildings but also to the visual and spatial aspects of the land.

The NPPF lists the five purposes of the Green Belt as follows:

As you can see, none of these purposes relates to environmental protection; instead they are focused on mitigating urban sprawl. Interestingly, these purposes were unchanged in the new NPPF update.

The first purpose of the Green Belt is to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas, which is the fundamental reason the policy was created back in 1938. This goal is designed to manage urban growth by maintaining a clear boundary between urban and rural areas, thus preventing cities and towns from expanding uncontrollably into the countryside.

The second purpose of the Green Belt is to prevent neighbouring towns from merging into one another, which is vital for preserving the distinct identity and character of individual towns and villages by maintaining clear physical separation between them.

The third purpose of the Green Belt is to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment. The objective is to preserve natural landscapes, agricultural land, and the rural character of areas surrounding urban settlements.

The fourth purpose of the Green Belt is to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns. As you would imagine, this goal is all about maintaining the unique identity, historical integrity, and visual appeal of towns with significant heritage.

The fifth and final purpose of the Green Belt is to assist in urban regeneration by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land. This objective centres on promoting sustainable development and reducing the need to encroach on greenfield sites by prioritising the redevelopment of previously used land.

England's Green Belt land covers approximately 16,384 km², which is about 12.6% of the country’s total land area, clustered around 15 urban cores. Looking at a Green Belt map, you can see they appear as rings of green around a built-up urban core. While you might think that means thousands of kilometres of rolling green, the reality looks a little different.

First and foremost, the largest and most famous Green Belt is London’s Green Belt. The Metropolitan Green Belt not only takes up 22% of the capital’s area, it also surrounds a wide range of towns including Luton, Guildford, and Chelmsford. The other largest Green Belt areas are clustered around major urban centres, including Merseyside and Greater Manchester (2,477 km²) and South and West Yorkshire (2,465 km²).

Although the Green Belt is a national policy, it falls on each local planning authority (LPA) to enforce, meaning that different interpretations eventuate. More pertinently, each of those local authorities is left with the task of somehow squaring local housing needs with this deeply restrictive policy.

One of the most prominent misunderstandings of the Green Belt is that it's primarily an environmental policy. On the contrary, the Green Belt is fundamentally a land use planning strategy for the prevention of urban sprawl and wasn't designed with ecological or biodiversity aims at its core. This means that any environmental advantages are unintended consequences rather than the main objectives of the Green Belt policy, which many people find surprising to learn.

This fundamental misunderstanding has real consequences for planning decisions, as communities often oppose development based on environmental concerns that aren't actually relevant to Green Belt policy. The confusion stems largely from public expectations that don't align with planning reality.

One of the biggest causes of this misconception is the Green Belt's name itself. The word 'green' instantly evokes images of lush meadows and undulating plains of untouched countryside. However, the truth is that Green Belt is not green in the way most people imagine - it includes quarries, industrial sites, sewage works, and degraded brownfield land alongside the pastoral scenes that spring to mind.

While some stunning sections of the Green Belt ought to be preserved, the statistics reveal a more complex picture. Only 22% of land use in London's Green Belt is dedicated to environmental protection and the preservation of parks. Meanwhile, 76% of it - covering 26,000 hectares - serves various other purposes including intensive agricultural activity and golf courses. Much of this majority portion offers limited ecological value or public access, yet receives the same level of planning protection as genuine countryside.

This mismatch between perception and reality leads to heated public debates where environmental arguments are deployed inappropriately. Importantly, where ecological value is genuine, protections are already in place and include designations like Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) and sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs).

For a long time, development of any kind was extremely difficult to get over the line and would only be permitted if it met one, or ideally multiple Green Belt exceptions or special circumstances.

As mentioned in the introduction, there has been plenty of discussion about the Green Belt recently, particularly in the wake of the government’s announcements regarding significant Green Belt reform and planning system changes that were enshrined in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) in December 2024.

In a nutshell, the highly protected Green Belt will be reimagined, with sections that don’t meet the policy’s core purposes reallocated for much-needed housing. Those sections will be reclassified as ‘Grey Belt’ and be open for development where other options have already been exhausted. More on the Grey Belt shortly.

Under the previous system, Green Belt reviews weren’t compulsory, even in situations where an LPA fell grossly short of its housing need. Consequently, many areas with significant Green Belt coverage have historically faced challenges in meeting their housebuilding targets.

Now, the NPPF requires LPAs to review Green Belt boundaries in instances where they cannot meet their housing, commercial or other needs without adjusting these boundaries.

Now, not meeting housing need is classed as one of the ‘exceptional circumstances’ that justifies development in the Green Belt. However, if there is clear evidence that the new boundaries undermine the function of the Green Belt, then they will not be permitted.

When it comes to allocating land for development, the NPPF says that when releasing Green Belt land, plans should first prioritise 'previously developed land, then consider Grey Belt which is not previously developed, and then other Green Belt locations.'

As you can see, releasing premium Green Belt land for development is the last resort. However, the crisis is at a point where considering the last resort might be necessary.

About now you might be wondering how exactly ‘Grey Belt’ is defined. Well, on the 12th of December 2024 with the release of the new NPPF, we finally found out.

The revised NPPF describes ‘Grey Belt’ as 'previously developed land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143. ‘Grey Belt’ excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.'

For added context, the areas in footnote 7 include Areas of Outstanding National Beauty (AONB) and Sites of Special Scientific Interest (to name a few), and the three highlighted purposes are:

a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas

b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another

d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns

As mentioned, the new government proposes the use of Grey Belt land for development to address the housing shortage and meet the growing demand for affordable homes. The aim is to balance the need for new housing with the preservation of valuable green spaces by identifying and reclassifying areas within the Green Belt that are less critical to its primary purposes.

The tricky part is that at a strategic scale, nearly all Green Belt land makes a significant contribution to at least one of these three key purposes.

Additionally, there is the potential for subjective assessments of what constitutes a ‘strong contribution’ to these three purposes, which could cause an uneven distribution of ‘Grey Belt’ sites and exacerbate regional disparities in housing availability.

The assessment of Green Belt land is guided by specific criteria, each purpose with distinct benchmarks that consider strategic and spatial variations in the Green Belt's function.

To evaluate how well parcels of land support these intended goals, town planners and urban designers employ a three-point scale: significant, moderate, or limited/no contribution to the Green Belt purposes.

This allows for a nuanced evaluation of each land parcel's unique contribution to the overall Green Belt function and ensures the right land is being allocated for protection against development. Importantly, this information will also inform how councils will reshape their Green Belt boundaries.

With a new NPPF locked in, the future for the Green Belt is going to look very different, but not unrecognisably so.

As touched on earlier, the Green Belt policy has endured for a long time, largely due to the public’s misunderstanding of its true purpose as a tool for mitigating urban sprawl, rather than for environmental protection. Therefore, any change when it comes to building in the Green Belt will feel significant.

With the reallocation of Green Belt land into Grey Belt, we will see more homes cropping up to make better use of the land. Plus, the reintroduction of mandatory local housing targets will compel local authorities to approve more development than perhaps they otherwise would and, as mentioned above, review their Green Belt boundaries to make space for housing in cases where all other avenues have been exhausted.

In terms of what new development in the Green Belt will look like, the government has introduced some golden rules that major development needs to adhere to. This includes:

With these provisions in place, we will be seeing more affordable homes being built in the Green Belt which is a fantastic thing. Plus, there will be improvements made to green spaces and to infrastructure when needed, so some areas may even enjoy improvements.

Importantly, what we won’t be seeing is skyscrapers popping up in the countryside. A key priority of the government's Green Belt reform is to release land that is unworthy of its protected status and continue to safeguard land that plays an important role in containing urban sprawl.

While there will no doubt be backlash to any building going ahead on the Green Belt, the reality is that people need places to live and there are parcels of well-connected, underutilised, environmentally overvalued land that can help provide the land to do that.

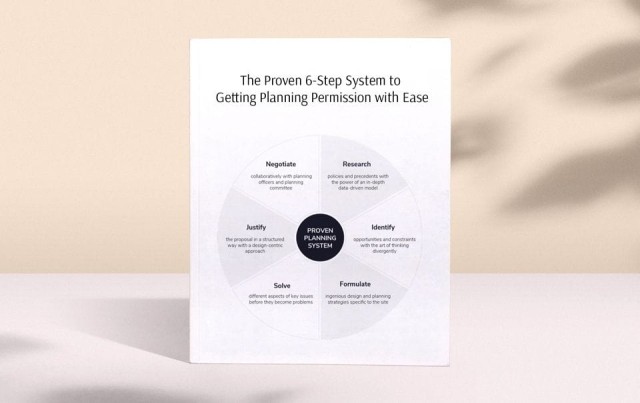

While the path to planning permission in the Green Belt is undoubtedly challenging, it's not impossible. A lesser-known fact is that exceptions and special circumstances exist which can allow for securing planning permission. However, these opportunities are typically leveraged only by a select group of opportunistic and strategic developers.

At Urbanist Architecture, we are a multidisciplinary architecture and planning practice rapidly earning a reputation as one of the country's leading firms, particularly in Green Belt planning permission. We excel at producing results that meet council expectations while exceeding those of our clients.

If you would like to learn more about the Green Belt, want to stay abreast of the latest updates or to discuss your project in the countryside, please get in touch with us today.

Given your interest in the Green Belt, I thought I’d let you know about our new book, ‘Green Light to Green Belt Developments’.

As discussed throughout this article, the Green Belt is one of the most contentious and misunderstood pieces of planning policy in England and it’s a topic we at Urbanist Architecture have a lot of experience working with. For this reason, we decided to pool our learnings and pen a book delving deep into the Green Belt from every possible angle.

'Green Light to Green Belt Developments’ investigates the policy's biggest winners and losers, explores its connections to climate change and the housing crisis, as well as what the future might hold. It also looks at the history of the policy and how it’s managed to endure while other policies have evolved and adapted with the times. Of course, it also identifies the exceptions and special circumstances that exist for permitting development in the Green Belt, so you can better your chances of gaining planning permission.

We’ve written this book for anyone seeking a more rounded understanding of one of England's most debated urban planning issues, making it accessible to both industry professionals and the general public.

Whether you are a landowner in the Green Belt wishing to understand the potential for land value uplift or a developer planning to build new homes in the Green Belt, this book is an essential read. Order your copy now.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message