Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

In December 2024, the government introduced one of the most significant shifts in planning policy for a generation. A revised National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) unveiled the Grey Belt — a new category within the Green Belt, designed to release land for development while safeguarding its core purpose.

Since then, planning decisions have started to shift. Refusals are being overturned. Developers are advancing schemes once thought unviable. And a growing number of councils are rethinking what Green Belt protection really means.

But what exactly is Grey Belt?

How do you know if your site qualifies?

And, most importantly, could this policy be the key to unlocking desperately needed housing?

This article sets out the answers.

Let’s begin by unpacking exactly what Grey Belt land is and why it’s reframing the debate around untouchable land.

Grey Belt in planning refers to land within the Green Belt that is either previously developed or contributes only weakly to its core purposes. These areas typically offer limited value in preventing urban sprawl, keeping settlements separate, or preserving the character of historic towns, and may be considered suitable for sustainable development.

But where did this term come from and why does it matter now?

Recognising the need for targeted Green Belt reform, the Grey Belt designation was formally introduced in the new NPPF 2024, clarifying which parts of the Green Belt can be considered for development.

The official definition sits in Annex 2 (Glossary) of the NPPF December 2024:

'For the purposes of plan-making and decision-making, 'Grey Belt' is defined as land in the Green Belt comprising previously developed land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143. 'Grey Belt' excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.'

This definition is deliberately broad. Grey Belt land includes obvious candidates like disused petrol stations, surface car parks, and edge-of-town scrubland - but it extends far beyond these examples, covering any Green Belt land that plays a weaker role in fulfilling its core purposes.

The operative policy framework sits in paragraph 155 of Section 13, which establishes four tests that determine whether Grey Belt development is "not inappropriate" in the Green Belt. Pass all four tests, and your development bypasses the need for very special circumstances entirely.

The detailed assessment criteria - how to evaluate whether land "strongly contributes" to purposes (a), (b), or (d) - are set out in the February 2025 Planning Practice Guidance on Green Belt. This guidance provides the technical backbone for determining Grey Belt status.

Put simply, for land to be considered Grey Belt, it must be previously developed land and/or any other land that plays a minimal role in:

However, Grey Belt does not include land that benefits from strong environmental protections or planning restrictions, where national policies provide a clear reason for restricting development. These include:

These designations override Grey Belt status, meaning that even if land meets the Grey Belt definition in terms of its contribution to Green Belt purposes, it cannot be considered suitable for development due to these overriding national planning constraints.

While Grey Belt designation removes some traditional barriers to development, it does not guarantee planning permission. Each proposal is assessed individually, with local planning authorities considering a range of factors to determine whether the development is appropriate. This includes the following factors:

Even if a site qualifies as Grey Belt, securing planning permission depends on meeting these planning requirements and demonstrating wider benefits that align with national and local policies.

On the 27th of February 2025, the government released an updated Green Belt Planning Practice Guidance (PPG), designed to help local authorities assess which developments should and shouldn’t be approved on Green Belt land, and to help them allocate Grey Belt land when forming local plans.

The updated PPG provides critical guidance on identifying, assessing, and unlocking Grey Belt land for development, setting a clearer direction for local authorities and developers. With the government under pressure to tackle the housing crisis while maintaining environmental protections, this guidance is already influencing planning decisions across England.

To keep things as simple as possible, we've rounded up the key updates you need to know.

As mentioned above, a key purpose of the Green Belt is to ‘check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas.’

However, the PPG now clarifies that not all undeveloped land contributes equally to preventing sprawl. Instead, it defines sprawl as land where development would create an incongruous pattern - for example, an extended “finger” of development projecting into the Green Belt.

Furthermore, if a site is physically constrained by features such as topography, rivers, or roads, or if it is partially enclosed by existing development in a way that does not result in an irregular expansion, the PPG suggests that the site does not significantly contribute to checking unrestricted sprawl and is, therefore, potentially suitable for development.

Interestingly, this clarification played a key role in a recent planning appeal in Beaconsfield, where an inspector dismissed a 120-home development, ruling that despite being surrounded by major roads, the site still served as an important barrier to urban sprawl.

This decision highlights how Grey Belt classification remains subject to interpretation and will continue to be shaped by case law.

This update relates to purpose b, ‘to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another.’

Historically, local councils have often included villages and hamlets alongside towns in their local plans.

However, the updated guidance specifies that purpose b pertains exclusively to towns, explicitly stating that "villages should not be considered large built-up areas."

Without question, this distinction is crucial, as many past Green Belt assessments classified land between villages as essential for preventing urban expansion, despite Green Belt policy originally being intended to curb the spread of large urban centres.

By clarifying this, the guidance reinforces that Green Belt protections should focus primarily on towns and cities, rather than unnecessarily restricting growth in smaller rural settlements.

Our analysis of major residential Grey Belt decisions reveals a compelling pattern: ten out of sixteen approvals involved village locations.

The Castle Point decision on the Daws Heath scheme demonstrates exactly why this matters. The Inspector devoted substantial reasoning to a single critical question: is Daws Heath a town or a village?

The conclusion was village, based on its limited range of services and facilities, which fundamentally transformed the assessment. Once classified as a village, the site couldn't strongly contribute to preventing urban sprawl (purpose a) or town merging (purpose b), and the 173-home development was approved.

This creates a powerful strategic advantage: if your site adjoins a village, you've effectively neutralised the two most challenging Grey Belt tests before evaluating any site-specific characteristics. The barrier to entry drops dramatically.

The approval in St Albans for 550 homes with community facilities is a clear sign of where things are heading. Twelve months ago it would have struggled to get through. As village sites become the primary path to Grey Belt approvals, village classification is changing the limits of the Green Belt.

If your site is located between two towns (not villages - specifically towns), that alone does not mean it plays a significant role in preventing their merger, even if development would reduce the physical distance between them.

The updated guidance on purpose b makes this clear. First, a site only has a strong relevance to purpose b if it forms a substantial part of the gap between towns. But even then, what truly matters is visual separation - how people perceive the towns' distinctiveness, rather than just their physical proximity.

In essence, this means that if a development site is shielded from view by existing buildings, dense woodland, or significant changes in topography, then it may not be considered as strongly contributing to preventing the merger of towns.

According to the new PPG, "if development is considered to be not inappropriate development on previously developed land or Grey Belt, then this is excluded from the policy requirement to give substantial weight to any harm to the Green Belt, including to its openness." This represents the most significant shift in Green Belt rules for a generation.

Traditionally, any development in the Green Belt was presumed harmful and required 'very special circumstances' to justify approval which is an exceptionally high bar that made development extremely difficult. The new Grey Belt provisions fundamentally change this by creating development that is not considered inappropriate and therefore does not require very special circumstances justification.

Green Belt openness assessment has evolved through key cases. Turner v Secretary of State (2016) established that openness encompasses both spatial and visual dimensions, while Samuel Smith Old Brewery v North Yorkshire County Council (2020) confirmed it as "a matter of planning judgement, not law." However, the High Court's landmark Mole Valley District Council v Secretary of State (2025) judgment revolutionised the entire framework.

Mr Justice Choudhury definitively ruled that openness cannot be assessed separately for development qualifying as 'not inappropriate' under paragraph 155. The council had argued that the established Lee Valley precedent was 'wrongly decided and/or inapplicable' to their case, attempting to challenge decades of legal understanding about green belt openness. The Court rejected as "unarguable" attempts to apply openness assessment to qualifying Grey Belt development, holding this would "negate the purpose of the exceptions and undermine the policy change introduced by NPPF 2024."

So emphatic was the judgment that Mr Justice Choudhury dismissed all three of the council's grounds as 'unarguable', refusing permission for statutory review or appeal - a decisively final ruling that closes the door on similar challenges.

This creates two completely different pathways.

For traditional Green Belt applications, comprehensive openness assessment remains required using the Turner framework, with any harm requiring very special circumstances justification. The Upper Austby Farm appeal demonstrates this approach, where detailed analysis concluded a well-designed bungalow would enhance openness compared to existing shipping containers.

For Grey Belt development meeting paragraph 155 tests, however, the game changes entirely. There is no openness assessment, no substantial weight given to Green Belt harm, and crucially, no requirement for very special circumstances. The complex, expensive analysis that has characterised Green Belt applications is replaced by straightforward policy compliance tests.

In simple terms, if your development qualifies under paragraph 155, it is not inappropriate development. This means it cannot be considered harmful to the Green Belt, including any impact on openness, and does not need to demonstrate 'very special circumstances'. Instead of the punitive presumption against development, qualifying Grey Belt sites are subject to ordinary planning balance.

This builds on Lee Valley Regional Park Authority v Epping Forest District Council (2016), which established that 'appropriate development is deemed not harmful to the Green Belt.' The Mole Valley judgment extends this principle to all 'not inappropriate' development, including Grey Belt sites.

The practical impact is transformative.

Previously, Green Belt developers faced the near-impossible task of proving very special circumstances while overcoming substantial weight against any harm. Now, qualifying Grey Belt development bypasses these hurdles entirely. Local authorities cannot refuse applications based on subjective openness concerns, such an approach would be legally unsound following Mole Valley.

In other words, the council should focus their scrutiny on whether the site genuinely qualifies as Grey Belt under the five tests - not on whether development might theoretically impact openness. That battle's already been won by the policy framework itself.

The key distinction is binary: inappropriate development requires very special circumstances and faces substantial weight against any Green Belt harm; not inappropriate development (including qualifying Grey Belt) requires neither. The question shifts from "can you prove very special circumstances despite Green Belt harm?" to simply "does this qualify under paragraph 155?"

For practitioners and landowners, this creates a clear strategic choice: pursue the traditional route with its very special circumstances requirement, or demonstrate Grey Belt qualification to access the streamlined approval pathway that the courts have definitively endorsed.

Despite this legal clarity, some councils remain resistant - Mole Valley District Council expressed being 'surprised and disappointed' by the ruling and plans to raise concerns with the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, though notably they're not pursuing further court action, acknowledging the finality of this judgment.

While a big part of the new PPG focuses on how councils should define land parcels when reviewing the Green Belt and Grey Belt for future local plans, this process will take time, and so applications and appeals for individual Grey Belt sites will continue in the meantime.

Right now, the key question isn’t whether some large, previously defined Green Belt area fits the new Grey Belt definition. Instead, the focus is on your specific site - the land in the application.

Bottom line: Does your site strongly contribute to Green Belt purposes A, B, or D?

Remember, that's what matters - not the broader area it sits within.

The Green Belt’s Golden Rules apply to all major residential proposals in the Green Belt, not just those on Grey Belt land.

But here’s the interesting part: Golden Rules also influence the assessment of non-major developments, as the principles of sustainability, affordability, and infrastructure provision remain central to decision-making in the Green Belt. While non-major developments may not be subject to the full set of requirements, aligning with these principles can still strengthen a planning application.

The crucial factor at play here is this: If a development complies with these rules, it will be afforded “significant weight in favour of the grant of permission” under Paragraph 158 of the NPPF. This recognition reinforces the government’s commitment to delivering sustainable growth while maintaining the Green Belt’s essential functions.

Let’s look at one of the recent examples of Grey Belt planning applications. A scheme in Kent provides a clear case of how compliance with the Golden Rules can influence planning outcomes. To meet these principles, the developer raised the affordable housing provision from 40% to 50%, a decisive move that played a key role in securing approval.

The takeaway? This adjustment demonstrates how incorporating higher levels of affordability, necessary infrastructure, and public benefits can significantly strengthen a planning application, particularly in areas where housing need is high.

The same principles apply to smaller-scale developments, where adherence to key sustainability and housing delivery objectives may enhance the case for approval, even if the site is not classified as a major development.

While the introduction of Grey Belt policy has led to significant planning approvals, decisions by planning inspectors have been inconsistent, reflecting differing interpretations of the new policy across the country.

For instance, in St Albans and Hertsmere, Grey Belt designations were accepted, leading to approvals for major housing and infrastructure projects. These decisions aligned with the government's intention to prioritise previously developed or low-performing Green Belt land for development.

In contrast, in Beaconsfield, an inspector took a far stricter approach, rejecting a 120-home development despite the site being enclosed by major roads. The decision rested on the site’s continued role in preventing urban sprawl, despite its physical separation from open countryside. This case highlights that while Grey Belt aims to streamline development approvals, some inspectors still adhere to traditional Green Belt protections, particularly where past assessments categorised land as serving a containment function.

Similarly, in Surrey, a mixed-use development including housing and commercial space was refused despite being located on a waste processing site. The inspector acknowledged that the land met the Grey Belt definition but argued that its partial enclosure by existing infrastructure was insufficient to justify development.

The bottom line?

The Grey Belt policy is still developing, and and outcomes of various examples of Grey Belt proposals demonstrate that decisions by planning officers and inspectors remain worryingly inconsistent. Local plans and emerging case law will play a crucial role in defining how Grey Belt land is assessed and approved moving forward. For developers and landowners, monitoring planning appeal outcomes is essential to understand how different factors - such as a site's history, physical constraints, and role in preventing urban sprawl - affect decisions.

That said, the early evidence from Grey Belt appeals - though not yet appearing in official statistics - suggests success rates well above even the inquiry average. Our analysis shows multiple approvals securing inspector support through straightforward application of paragraph 155 criteria, without needing to demonstrate very special circumstances.

This trend isn't coincidental - it reflects a structural change in how Grey Belt applications are evaluated: The revised NPPF has created a new pathway where qualifying Grey Belt development is assessed under ordinary planning balance - a dramatically different starting position that explains why approval rates are rising.

Think the Grey Belt is insignificant? The numbers tell a different story and they demand our professional attention.

Digging into the research uncovers a stark contrast in findings. Various assessments highlight significant disparities in the measurement of Grey Belt land.

The Times suggests roughly 3% of England's Green Belt (approximately 46,871 hectares) could be classified as Grey Belt, while Knight Frank has identified over 11,000 previously developed sites with potential to deliver between 100,000 and 200,000 dwellings.

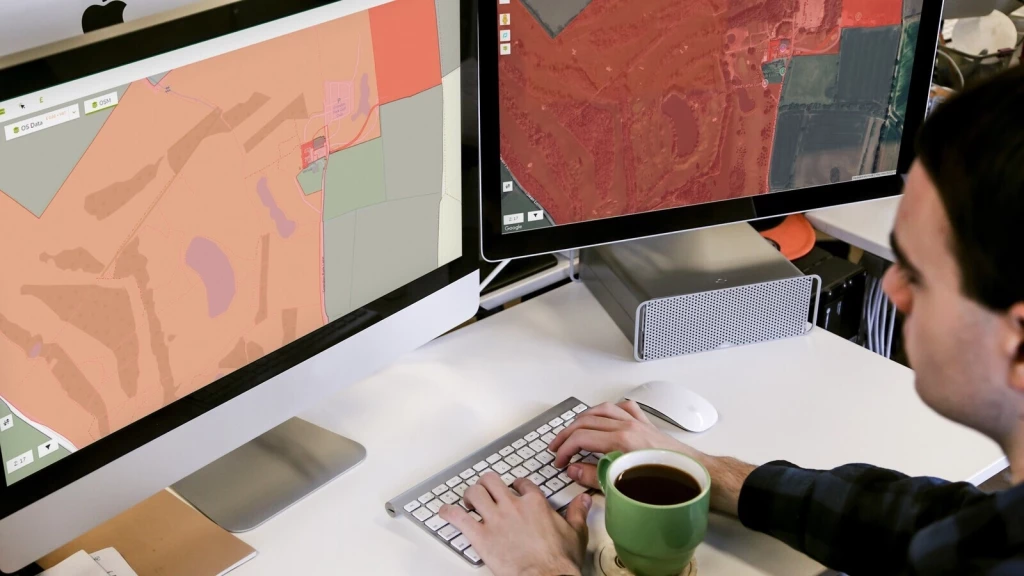

More ambitious figures emerge from LandTech, which proposes that up to 300,000 homes could be constructed on such land. Searchland offers the most expansive estimate: 30,597 Grey Belt sites potentially accommodating 3.4 million homes.

What does this tell us?

This variation illuminates both the ambiguous nature of Grey Belt classification and divergent assumptions regarding development capacity. Whilst some adopt a cautious stance, concentrating on specific parcels and reasonable housing densities, broader assessments highlight the considerable volume of land that could be repurposed.

Here’s the common thread: Across all analyses, Grey Belt land represents a significant, yet underexploited opportunity. But there’s a catch. Unlocking these sites depends on how planning officers and inspectors interpret the revised NPPF and Green Belt PPG.

Even accepting only the most conservative estimate, the Grey Belt presents substantial potential for helping to address the UK’s housing crisis, offering a pragmatic solution that balances development needs with environmental protection.

Strategically, Grey Belt was introduced to unlock sites for housing while maintaining essential Green Belt protections. By designating underutilised or previously developed land that makes a limited contribution to Green Belt purposes, the policy directs growth to areas where it is most sustainable.

This approach enables local authorities to meet housing targets while minimising the need for widespread Green Belt release. It also helps tackle the UK's housing crisis by optimising land use, easing pressure on greenfield sites, and simplifying the planning process for appropriate developments.

But there’s a challenge: To realise this potential, we believe that political courage is the cornerstone of successful Grey Belt development. Without resolute leadership and precise policy guidance, local authorities will inevitably falter, constrained by fears of public opposition and legal challenges.

Firm government backing is essential to empower planning officers, streamline development processes, and deliver the sustainable housing growth that our communities so urgently require.

As part of their Green Belt reform, the government has pledged to prioritise developing Grey Belt and brownfield land, grant new devolved planning powers to regions, and reform compulsory purchase rules for faster land assembly.

But that's not all. The new government will also identify locations to create a series of new towns to help alleviate housing shortages. This involves building entirely new communities with integrated infrastructure, public services, and green spaces. The objective of these new large-scale towns is to provide high-quality, affordable housing and foster sustainable residential-led developments.

The relaxations in the planning process for building within the Green Belt will be guided by the previously mentioned Golden Rules which include:

Additionally, when it comes to allocating Green Belt land for development, LPAs have been instructed to first consider brownfield land, then Grey Belt areas that are not previously developed, before reviewing other Green Belt locations for housing development as their final option.

It’s crucial to pinpoint a couple of Green Belt myths that, in my opinion at least, are mostly to blame for these changes not going ahead sooner.

If you’re worried that these changes mean environmental destruction, then I need you to read the two key points below.

Let’s take a look.

One common misconception about the Green Belt is that all of it is lush, verdant, and pristine.

While much of the Green Belt is indeed green, a significant portion does not fit this idyllic image. In fact, around 65% of Green Belt land is agricultural, but much of the remainder consists of former industrial sites, low-grade farmland, or land with limited ecological value.

The Green Belt is not green in the environmental sense either. In London, for example, 76% of the Green Belt is classified as low environmental quality, often featuring defunct agricultural buildings and areas with minimal biodiversity. Additionally, a substantial portion of the Green Belt is privately owned and inaccessible to the public, challenging the notion that it serves as a shared public resource.

Though many people believe that the Green Belt exists to protect wildlife, special landscapes, and historic assets, the reality is that the Green Belt policy isn’t primarily concerned with environmental preservation; its primary purpose is to contain the expansion of cities and prevent urban sprawl.

With this in mind, the term 'green' can be misleading, as the designation and protection of Green Belt land is based on its location rather than its environmental or scientific value.

The Campaign to Protect Rural England (CPRE), a lobbying group with strong beliefs against building in the Green Belt, has expressed nuanced and sometimes mixed reactions to the concept of Grey Belt development. In short, CPRE's view on Grey Belt could be described and summarised as cautiously supportive.

CPRE acknowledges that some low-quality Grey Belt land may be suitable for development and argues that brownfield sites should be prioritised. However, estimates indicate that brownfield land alone could only meet housing demand for around four years, highlighting the need for alternative solutions.

That’s not their only concern. CPRE also argues that some degraded sites could be restored as valuable habitats rather than being developed, advocating for a case-by-case approach to ensure environmental protections are upheld.

And then there’s another issue. CPRE warns against speculative degradation, where landowners might intentionally degrade land to gain Grey Belt reclassification. To combat this, they call for strict environmental safeguards and robust planning controls.

As a solution, we believe that an independent commission can be established to provide the necessary oversight and uniformity to address these concerns effectively. This body could ensure that Grey Belt classifications are made transparently and equitably, preventing unethical practices and ensuring that environmental integrity is maintained.

The Green Belt was designed to prevent urban sprawl, not block housing where it's desperately needed.

Grey Belt offers a nuanced approach to restore this critical balance. To fully understand its potential, we must also consider the challenges that come with its implementation.

An often-overlooked point is that allocating Grey Belt land for development requires navigating the complex dynamics between local priorities and national standards. Because local authorities often focus on immediate economic benefits, this approach can overshadow the need for long-term environmental sustainability.

Conversely, national guidelines and design codes that standardise practices across regions might not deliver the type of relevant housing solutions effectively, leading to a one-size-fits-all approach that lacks local context, the unique characteristics and needs of individual local authorities. For example, while some councils may need high-density urban extensions, others might require lower-density suburban growth, making rigid national policies challenging to implement effectively.

The analyses conducted by Knight Frank, which identified over 11,000 Grey Belt sites across England, also highlights that these sites are not evenly distributed. Remarkably, 41% of these sites are concentrated within London’s Green Belt, with significant numbers also found in Greater Manchester, Birmingham, and South and West Yorkshire.

In practical terms, this uneven distribution implies that some regions may gain more from Grey Belt development than others, potentially intensifying regional disparities in housing availability and economic growth. Addressing these disparities requires careful planning and targeted support for regions with fewer Grey Belt opportunities.

The simple truth is that if we are to meet the growing demand for housing in the UK, it is essential that we release some Green Belt land for development. The release of even a small percentage of the Green Belt, including low-quality Grey Belt land, could significantly help accommodate several years' worth of housing needs but only if planned and designed holistically. This must be complemented by investment in transport, utilities, and local services to prevent placing excessive strain on existing infrastructure.

The government has also recently announced it is reinstating mandatory local housing targets, which were relaxed by the previous government. To that end, by local councils releasing publicly owned Grey Belt land to national housebuilders and SME developers, the delivery of new sustainable communities can be significantly accelerated.

To move forward, greater clarity is needed on how Grey Belt sites will be prioritised within local plans and whether additional funding will be allocated to support their infrastructure needs.

While Grey Belt designation offers a pathway forward, winning approvals demands both meticulous site analysis and strategically crafted justification for the application.

Our team of Green Belt architects and planning consultants is fast earning a reputation as one of the country’s leading planning and architecture firms - particularly when it comes to Green Belt planning permission. We focus on achieving outcomes that align with the evolving Grey Belt policy while thoughtfully surpassing our clients’ ambitions.

In fact, we’ve written a whole book on it, which is available for purchase now if you’re interested.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message