Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The market is saturated. Profitable land is hard to come by. Budgets are tight. And there’s no guarantee of success. Once you’ve purchased the land, everything depends on the planning permission application.

Prior to approval, your project is hypothetical. The thousands of pounds you’ve poured into your passion project – the blood, sweat and tears – could all be for nought if the local planning authority rejects your application. If you succeed, the world is your oyster. If you fail, your investment could flop and it’s back to square one.

So how do you increase your chances of success?

Permission in principle (PIP) might be one answer.

This planning route may not be right for every project, but it is definitely something to consider as you seek solutions to your development woes. In this article, we’ll outline the fundamentals of permission in principle: what it is, why you might need it, and how to get it.

Permission in principle is designed to increase the efficiency of the planning process and deliver more homes.

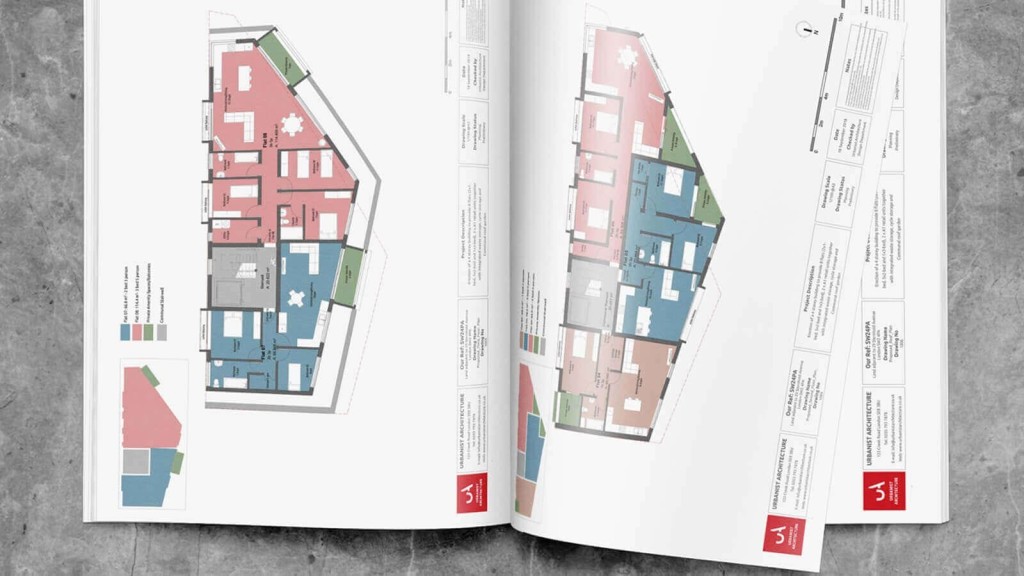

Current planning applications require a substantial amount of information upfront, even for outline planning permission. Permission in principle separates the absolute basics of ‘principle of development’ – land use, location and amount of development – from everything else ('technical details').

Via this route, you only need to establish the principle of development once. Then you can go on to apply for approval of the technical details, which will include the appearance of the building and its compliance with local and national policy requirements for space and amenity (outdoor spaces etc).

Ultimately, the permission in principle route is an alternative way of obtaining planning permission for housing-led development. This route involves two stages:

So how can a site be established as ‘suitable in principle’?

The permission in principle route is available for any site that might accommodate minor housing-led development, provided the development is not on land that is subject to Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) or Habitats legislation.

Permission in principle is subject to location, land use and the amount of development. The upper limits of the proposed development are up to nine homes, with less than 1,000 sqm of commercial floorspace and a site of less than one hectare.

Mixed-use sites with retail, offices or community spaces can be granted permission in principle, but housing must always occupy the majority of the overall scheme. Additionally, non-housing development should be compatible with the proposed residential development.

After permission in principle is granted, the proposal will then be assessed in greater detail. This is known as technical details consent (TDC), and it is described in greater depth below.

Following the grant of permission in principle, the site must then receive a grant of technical details consent before the development can proceed. This is effectively the same as granting planning permission.

A technical details consent application should include plans and supporting documents such as a design and access statement or any statutory requirements such as conservation or listed building assessments.

So why pursue permission in principle? Why not just dive into a full planning permission application? Here are two important reasons for pursuing this type of planning permission.

Permission in principle can be a more cost-effective route than a full planning application, especially in cases where the viability of a site is uncertain.

As of 1 April 2025, the fee for a PiP application is £512 per 0.1 hectare, which is significantly lower than the full planning application fee of £588 per dwelling (for example, £2,352 for a four-dwelling site).

PiP also requires far less upfront documentation, reducing consultant and preparation costs.

If the PiP application is unsuccessful, the developer only loses the £512 fee, whereas a full application would have involved considerably more time and expense. However, if PiP is approved, a second application - Technical Details Consent (TDC) - must still be submitted, which carries the same fee and requirements as a full planning application. This means the combined cost of PiP and TDC could slightly exceed that of a single full application.

Nonetheless, PiP can offer significant savings and risk mitigation for developers exploring smaller or more challenging sites.

Moreover, according to the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, Permission in Principle will make an important contribution to the delivery of new homes by increasing certainty regarding the suitability of land for less than ten dwellings.

It will essentially create a ‘zonal system’. In addition, land identified as suitable for development on brownfield registers can receive permission in principle.

When applying for Permission in Principle, an application must:

The fee for a permission in principle is £402 per 0.1 of a hectare for the amendment categories, which include:

The fee for non-material amendments to a permission in principle or technical details consent is £195.

The local planning authority (LPA) should make its decision within five weeks of receipt of the application, assuming it is valid and complete.

If the planning authority fails to issue a decision within this time period, the applicant may appeal to the Secretary of State – unless the LPA and the applicant have agreed ahead of time on an extension.

Once Permission in Principle has been granted, it will be in effect for three years and then ‘cease to have effect’.

Overall, permission in principle is not dissimilar to outline planning permission, and technical details consent is fundamentally the same as full planning permission.

In practice, permission in principle is only suitable for a fairly limited range of developments. It's best used for sites where you are unsure whether the local planning authority (LPA) will welcome development but you have no strong case for why a specific group of houses should be acceptable.

So permission in principle is not a shortcut to obtaining planning permission and will not actually save money when if you go all the way to the technical details consent stage. But if you’re a developer looking to reduce the risk associated with planning permission, you should read the guidance on permission in principle.

Urbanist Architecture is a London-based RIBA chartered architecture and planning practice with offices in Greenwich and Belgravia. With a dedicated focus in proven design and planning strategies, and expertise in residential extensions, conversions and new build homes, we help landowners and developers achieve ROI-focused results.

If you would like our advice on which is the best route to planning permission for your development and our help getting it for you, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message