Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

One of the things that alarmed a lot of people about the government’s 2020 proposals to reform the planning system was the idea that they would lose the right to object to local applications, including those made by their neighbours.

For many, this ability to object is a precious democratic right - at least until they try to build something themselves. And then it can all seem very different.

In this article, we’re going to explain what to do if you are on the wrong side of multiple planning objections.

The planning system provides a clear forum for public engagement: a three-week-long comments period follows the validation of any application. The case officer will often inform neighbours likely to be affected by a proposal and traditionally laminated notices are put up on nearby lamp posts (several high-tech alternatives to this are being explored).

If there is a parish or community council, they will also be informed, along with relevant specialists at either your council itself or the county council, like the tree officer, the ecologist or the highways authority.

The idea is that all parties have 21 days to comment on the proposal, either in support of or against it. Neighbours do not need to have been contacted by the council in order to give their views: any member of the public can comment on any planning application, regardless of where they live. But, as we will explain below, the council only needs to pay attention to relevant comments, either in favour or against.

Thankfully, the planning system has clear guidelines on what is a “material consideration,” or an issue that matters, in planning terms, during an application’s determination. Understanding what is and what is not a material planning consideration helps us support our clients whose applications have attracted negative local feedback.

For example, we recently secured planning permission for a client following a notably lively comments period: their application received a whopping 61 responses. (To give you a bit of context, the majority of our projects receive five comments at most, and very often none at all.) In another case, there were over 90 objections and yet the council officers judged that none of them raised questions that had not been answered in the application.

In order to formulate an effective public consultation response for the 61 objection case, we went through each of the comments in detail and separated out those that contained invalid objections. We then grouped the material planning considerations into seven main themes, and demonstrated how the collection of documents we had submitted as our application already predicted and addressed each of these questions.

At the heart of all of this are those material planning considerations. These matter in every instance, not only in cases that garner a significant amount of local pushback. That’s because effective planning proposals are ones that address material considerations from the very start of the design process.

So, whether you’re looking to object to a proposal in your neighbourhood, or conversely, to respond to the objections that your proposal has received, it’s important to first get a basic understanding of the factors that actually have an impact upon an application’s determination.

This brings us to a key question: what are material planning considerations?

Material planning considerations are matters that should be taken into account by a case officer while making a decision about a planning application.

These can include:

These are all factors that our planning consultants explore, alongside the relevant local and national policy guidelines in order to inform our design proposals. Every Urbanist Architecture planning application is accompanied by a design and access statement that identifies and explains in detail the material planning considerations on site.

A strong planning application will address each of the material planning considerations that apply to a site through a carefully researched development proposal. Essentially, it should anticipate objections and provide solutions to them as part of the design process.

This is exactly what we did with the 61 objection application. As we went through each comment, we began to realise that all of the material planning considerations raised – from impact on neighbourhood character to the potential flood risk presented by the proposed basement – had already been explored during our application process. That’s because these questions mattered to us, too, and our eventual submission addressed them through the input of specialist consultants.

We are aware that not everybody reads through all of the documents supplied in a planning application. It’s even possible that they have read none of the documents, and are just going by a description of the proposal from a neighbour, newspaper or local pressure group.

When there are a lot of objections, many of them will turn out to be duplicate comments, which counterintuitively do not carry much weight. Councils will take objections more seriously if they have clearly been written by the objector, and if that person shows they understand what they are talking about. Copy-and-pasting a stock response is likely to have a limited influence on a case officer’s decision.

We’ll now take a look at some valid objections to planning applications. This is as useful for applicants formulating a public consultation response as it is for residents seeking to make effective remarks.

Likewise, multiple objections from one address will not add weight to the cause of those objections unless - as is unlikely - each one is bringing up a different, new and valid point.

Given what we’ve just discussed about material planning considerations, it follows logically that a valid planning objection has to concern one of these factors.

Any of the following comments might constitute a valid objection to a planning application:

Of the 61 comments our application received, we would say that a little more than half raised material planning considerations – and therefore were valid planning objections. The others concerned issues like noise generated during construction or individual design preference. However fair those comments are, planning guidance does not allow a case officer to take these into account during their determination process.

Let’s take a look at some of the kind of remarks that would be considered invalid objections.

Our public consultation response only addressed the comments that were considered valid planning objections. This is because we understood that the case officer would recognise and ignore invalid ones.

It’s important to understand that planning decisions can be made by one of two groups of people: the planning department and the planning committee. The officers who make up the planning department are council employees - civil servants who have training and usually academic qualifications in planning. The planning committee is made up of elected councillors who might or might not have experience in planning, architecture or property development.

In theory, all planning decisions are the responsibility of the planning committee. In practice, the vast majority of planning applications end up as “delegated decisions” - left to the council officers to deal with. It is usually - although not always - in the interests of the person or company putting in an application to have it dealt with as a delegated decision. Essentially, you would rather have it judged by a knowledgeable professional than subject to the more political atmosphere of the planning committee.

It’s possible to exaggerate this difference. Many planning committees are dedicated and know a lot about their subject. And the committee always gets a thorough briefing from the planning department before they discuss the application. Even so, a delegated decision will always be quicker, at the very least.

And this is where objections can come into play. Firstly, some councils have a threshold number of objections above which even if planning officers recommend approval, an application will need to be handed over to the committee for the decision. For other councils, it’s more of a judgement call based on the importance of the proposal. Either way, that’s where the neighbours or public dislike of the project can cause problems, and why you need your response ready.

As we’ve said, councils request comments within a time limit: usually within three weeks of notification. However, they are obliged to consider any comments received before the determination is made. So, even after the comments period ends, it is possible that new considerations will be raised that become relevant to the application.

This happened in our case. We, therefore, had to strike a balance when determining the timing of our response. If we sent the council our statement too early, we could have missed new comments, but if we waited too long, we ran the risk of a decision being made before we submitted a formal reply.

In addition to timing, the clarity of a public consultation response is also important. Our document organised all of the material planning considerations raised into seven key themes, and then demonstrated very explicitly where our application materials had included information to address each point.

Eventually, understanding the material planning considerations that were most relevant to our application site allowed us to emerge from the process successfully. We were ultimately granted planning permission after formulating a response to the 61 objections that we received on a development proposal.

That’s a number that might make you imagine that this was a development of a dozen homes, not a single three-bedroom house. This was on what could be seen as a backlands site, but, crucially, one that fronts onto a street. Currently, there’s a garage and a couple of sheds at the bottom of a big garden. Before we got involved, there had been an attempt to get planning permission with a design that was aiming for a smaller version of the large 1930s houses to either side of the plot.

That application drew fierce local opposition and also had a couple of seemingly intractable practical problems. It was withdrawn.

We were brought in to take a fresh approach. What was clear was that mimicking the sizeable local houses at a reduced scale was neither respectful to them nor a sensible response to the constraints of the plot. Instead, we worked up design studies for a house that would keep a lower profile but provide more space and have a distinctive look that would complement the local character rather than weakening it with pastiche.

Crucially, at this point, although we were confident that we had achieved a house that looked great externally and worked well internally, we needed to make sure the application was unassailable when it came to the material considerations. The client agreed, and commissioned a tree survey, a daylight/sunlight report, a transport survey and a basement impact assessment.

We were anticipating some objections, and wanted to have all the answers ready in advance.

And yes, it turned out there were those 61 objections, which for an application for a single three-bedroom house is pretty spectacular.

But we were prepared. And when the planning officer read through all those comments, he was able to see that all the legitimate concerns had already been addressed. We didn’t need to provide any additional information – it was all there at the council’s fingertips.

And that put them in a position to reach a swift and positive decision.

The lesson is that it can be possible to get planning permission for what seems like a very difficult site. The key elements are an applicant who is committed; a local planning authority that is willing to engage imaginatively and constructively to work towards the good-quality housing the borough needs; and, not least, an inspired design team backed up with planning smarts.

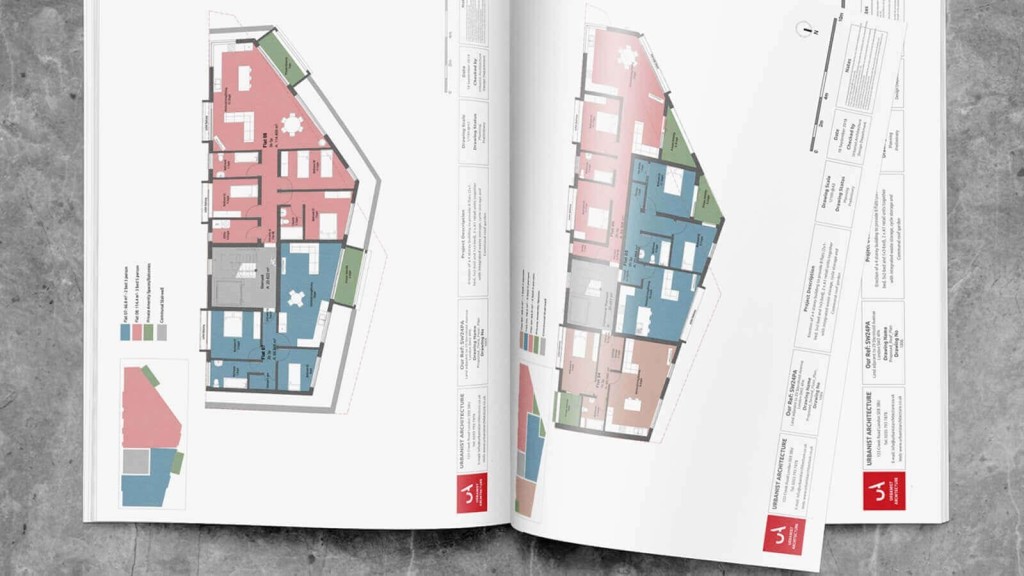

In another instance, a project of ours involved a slightly more substantial scheme. We helped a client craft a detailed planning submission on an irregularly shaped site that could best be described as a pie slice, where the crust lines the curve of a residential street. The back of the plot, where the garden sits, ends in a sharp angle – presenting us with the challenge of using space efficiently.

We and the client agreed that the erection of multiple new homes on site would better utilise the available land area while more productively contributing to local housing stock. Our proposal supported the demolition of an existing 1930s detached bungalow with a 1980s extension and detached garage, in order to erect three two-bedroom terraced houses with parking, cycling and refuse storage.

Such a scheme is not something that we would craft lightly: after seeking detailed pre-application advice from the council, we also sought a parking stress survey and produced both a sunlight study and sustainability statement. All of this information allowed us to produce a well-researched application that we were confident in.

However, our full planning submission received 16 objections and eventually went to a committee hearing. The main issues that were raised had to do with the proposal’s density and its potential impact on the character of the surrounding area.

People also questioned what impact the scheme might have on neighbouring amenity and privacy, and in addition, the safety of the proposal from a highways perspective - given its access along a curved street and potential impact on traffic generation.

Each of those concerns were fair, which is why they were heard by the committee. But this was another instance in which every question raised had already been answered by our design and access statement.

After assessing the information that we had provided, the committee found that the development would not cause any significant harm to the amenity of neighbouring occupiers, and additionally, would not negatively impact the highway. They therefore recommended the application for approval.

In sum, knowledge of the material planning considerations relevant to a tricky site again helped us secure approval for our client, even after a number of valid objections brought the case to committee.

It’s an example of success that embodies our philosophy at Urbanist Architecture, where planning research directly informs and strengthens every design proposal that we create.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message