Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Would you like to see England full of beautiful buildings and beautiful places?

Why wouldn’t you?

Isn’t this what Americans call a “motherhood and apple pie” idea: who could be against that?

But the government’s obsession with its beauty agenda for architecture has a lot of people and organisations, including some Conservative-run councils, alarmed.

We’re going to examine what’s causing that concern, explain the design codes that are meant to be the instrument to make this all happen and break down what’s new and what’s not about the government’s proposals and what the “fast track for beauty” is.

The first big step in the government’s beauty-in-architecture campaign was setting up the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission in 2018.

The commission’s task was:

“to tackle the challenge of poor quality design and build of homes and places, across the country and help ensure as we build for the future, we do so with popular consent.”

That doesn’t seem to be an outrageous idea. However, the membership of the Commission had some people worried, especially the co-chairs: right-wing philosopher Sir Roger Scruton and Nicholas Boys Smith from the pressure group Create Streets, both of whom seemed to feel that almost everything about modern cities was a mistake.

There was a suspicion that a very narrow definition of what a beautiful building should be was going to emerge, one that believes that architecture was perfected around 1780 by men inspired by ancient Greece and Rome and most of what has been built since is regrettable.

If all this had just been about a report trying to gently steer the design trends in the country in a certain direction, it would have been easy to ignore.

How many words are produced by high-minded commissions every year, and how much effect do they have on everyday life?

Hundreds of thousands and very little, most people would say. But the government had a very specific purpose for its beauty agenda. You might think that to end “poor quality design and build”, you would be asking developers to take more care and add more thought to what they are doing. But a key part of the government’s ambitions for reforming the planning system, outlined in the white paper Planning for the Future, is a “fast track for beauty”.

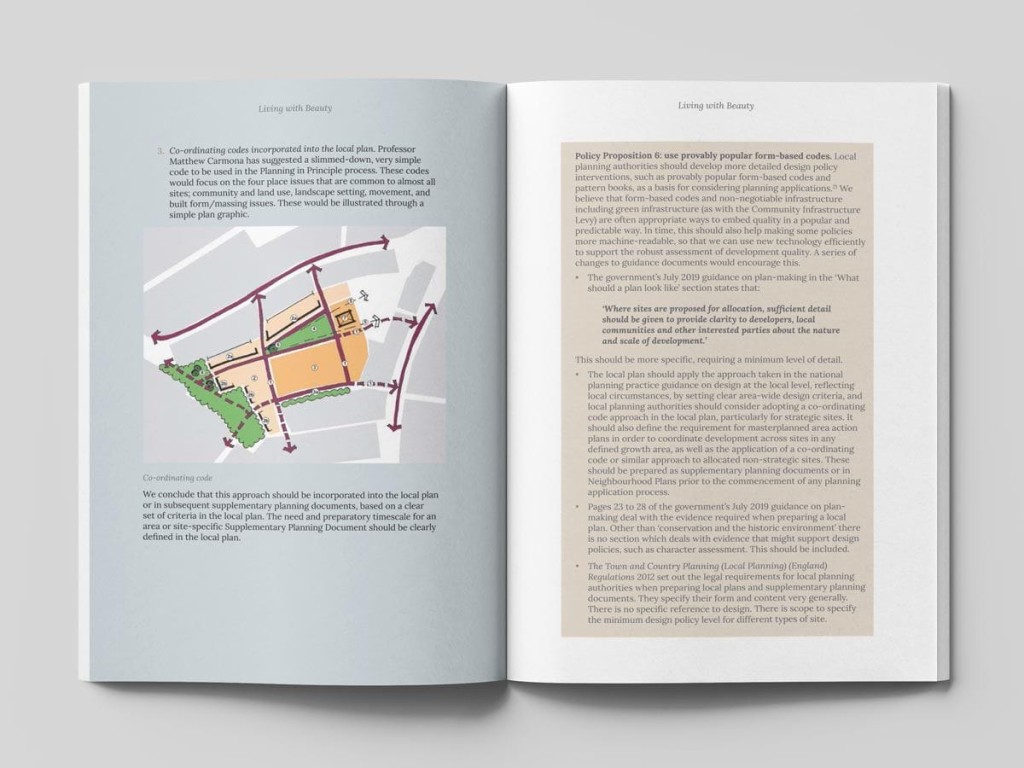

This, broadly, is how it would work: in each area of the country, we will get together and agree on what we think the key elements of the local design style should be. Once our new design code is in place, anyone who puts in a planning application follows those guidelines will get a quick and easy path through the planning process.

New Forest in Hampshire has a Conservative-controlled council with its headquarters in a village of 3,000 people. It would seem to represent the England of traditional-style houses that the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission’s report Living With Beauty seems to dream of.

And yet, in its response to the Planning for the Future white paper consultation in autumn 2020, New Forest District Council responded to the question “Do you agree with our proposals for implementing a fast-track for beauty?”, with:

“No – this proposal is fraught with difficulties. How can 'beauty' be judged in any meaningful way? How can 'beauty' be defined? 'Beauty' and 'Sustainability' are not the same thing. Just because a building looks beautiful (whatever that means) does not mean that it is issue free in terms of all the other matters the planning system needs to address.”

So let’s take a closer look and explain…

Beauty…

Is it in the eye of the beholder? Or is it something more objective that we all recognise?

“How can beauty in architecture and design be defined?” seems to be the central question here.

You might feel it is the kind of question that is better left to philosophers than civil servants. (Maybe that’s why the government chose a philosopher, the late Roger Scruton, to head up the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission).

The government, though, thinks that they have a practical answer to that. We will know what beautiful buildings are because the rules will be set out in the new design codes. These are meant to be agreed locally, democratically, but they will take their lead from the National Model Design Code, which is currently being consulted on.

Here’s the curious thing, though: although the words “beauty” and “beautiful” appear 21 times in the announcement about the National Model Design Code (NMDC) consultation from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, when you actually read the draft Design Code itself, “beauty” doesn’t appear at all and “beautiful” only twice.

In fact, if you separate it out from the government’s bigger plans for the planning system and the statements made by government ministers about architecture, the NMDC doesn’t seem to be either radical or new. Indeed, for anyone who has studied urban design, it’s all very basic stuff about the best way to lay out streets and buildings. Its advice is mostly fairly uncontentious:

“The identity of an area comes not just from its built form and public spaces but from the design of its buildings. This is not about architectural style, but about key principles of building design.”

It also tells us that: “Well-designed homes and buildings are functional, accessible and sustainable” and that “Well-designed places should be accessible and easy to move around”.

Chances are, shown one of the new local design codes put together using the NMDC and the existing design guides many councils have, most people couldn’t tell the difference.

Let’s say, though, that councils follow the spirit of the government’s plans rather than the sober NMDC when they put together their own design codes. What would be the dangers of using design codes focused on delivering beautiful buildings?

The fact that design codes will be deeply embedded into the planning system and local plans will be welcomed by many. That is because:

We don’t think there is anything terribly wrong with the idea of design codes – although nor is there anything new or different. And we agree with the terms of reference that were set for the Building Better Building Beautiful Commission – too many places have been poorly designed and shoddily built in this country.

There are three problems that we see.

The first is to do with that “fast track for beauty” – this seems to be a policy almost guaranteed to produce the opposite of good architectural design.

Rather than developers working with architects to create buildings and neighbourhoods that respond thoughtfully to their settings and planning departments judging those proposals carefully, the “fast track” will encourage builders to bung together a standard set of local elements – say, red brick, hipped roofs with dormers, prominent porches – and planners will be obliged to wave these applications through no matter how mediocre they are.

Secondly, applied too rigidly, these codes could harm the government’s other priorities. For instance, making the best use of brownfield sites to tackle the housing crisis. One of our favourite projects of last year was this one:

We created an architectural design concept that responded entirely to the weirdly shaped plot and turned its constraints into virtues. If you had tried to fit conventional rectangular buildings onto that site, you wouldn’t have got very far.

Meanwhile, although the government’s design guru Nicholas Boys Smith believes that the traditional London townhouse is an unbeatable classic, those homes are not suited to every situation. For instance, anyone who has to care for an elderly, mobility-impaired relative in a narrow (but certainly beautiful) Georgian house knows how far they are from matching contemporary standards of accessibility and all-age living.

Likewise, although sustainable technology can certainly be used in traditional-looking buildings, greater design freedom increases the possibility of designing zero-carbon buildings affordably.

And the hatred of the architecture of the postwar era espoused by some in the government might prevent the thoughtful reuse of these buildings, which is often the most environmentally helpful option, as advocated by The Architecture’s Journal’s RetroFirst campaign and backed by RIBA.

Finally, although however restrained the National Model Design Code seems to be, there have been statements from ministers that are a little more alarming. For instance, in 2018 then housing minister Kit Malthouse put out a tweet comparing a courthouse in Alabama and a building in Hyde Park.

He wrote, “Both built in the last 10 years. One will stand for centuries, one won't. Our new “Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission” will help us…”

A couple of thoughts: neoclassical buildings have a particular place in the history of the southern United States and it’s not one that should be celebrated. Secondly, Donald Trump insisted on neoclassical as the only style that could be used for new federal buildings – the new Biden administration swiftly consigned this edict to the dustbin of history.

But for anyone old enough to remember the late 1980s in the wealthier parts of the UK, it’s not public buildings with a totalitarian aura that you might be fearing. It’s the return of faux-Georgian mansions and mews, usually gated, that far from reviving the glorious tradition of the originals, mocked it with their clumsy design and shoddy workmanship.

Let’s respect our great buildings by not making bad copies of them.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message