Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

It’s difficult to think of a policy in the English planning system more controversial than the Green Belt.

While its supporters view it as an environmental measure designed to protect England’s natural beauty and wildlife, its detractors believe it’s deeply misunderstood; a stubborn obstacle standing in the way of solving the housing crisis.

So, who do we listen to?

In this article, I’ll be exploring both sides of this argument by delving deep into the persistent myths that continue to surround the Green Belt. My hope is that this analysis will help to clarify the purpose of the Green Belt and shed light on what it’s designed - and crucially what it’s not designed - to do.

Before I begin debunking the dominant Green Belt myths, it’s important we take a look back at the history of this contentious policy so we can better understand its role in today’s context.

Let’s dive in.

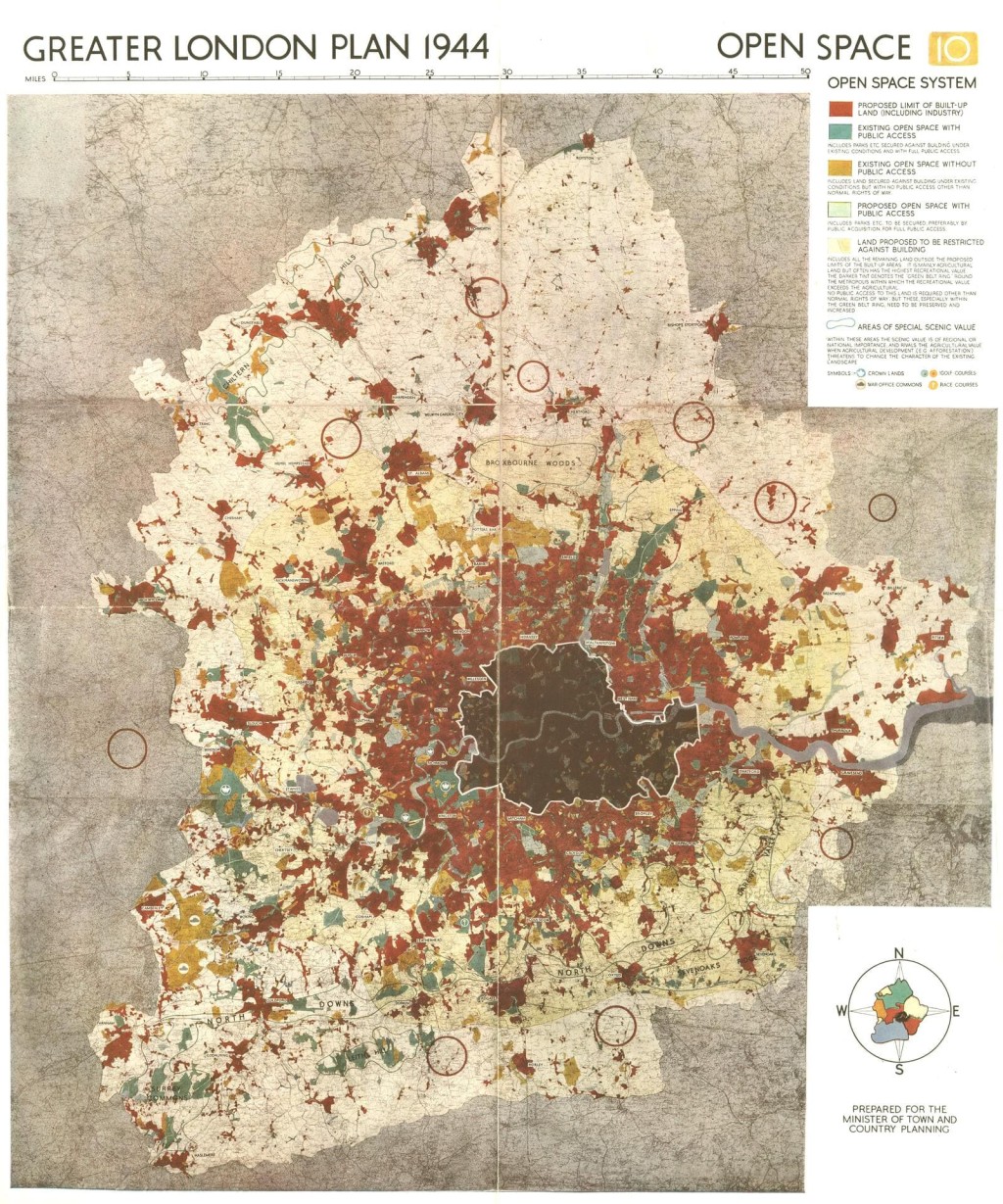

The Green Belt’s history is extensive, with the seeds of today’s policy being introduced way back in the 16th century when Queen Elizabeth I first drew a 3-mile ring around London to prohibit the development of any land that had not already been built on.

Though the history of the policy dates back almost 500 years, in the interest of time, we’re going to be skipping a couple of centuries and limiting our history lesson to a brief review of the last 150 years.

This brings us to the late 1800s and Ebenezer Howard’s ‘Garden City Movement’.

Howard was a highly influential town planner who believed that his garden cities could combine the benefits of urban and countryside living, offering residents the best of both worlds. The idea arrived in a context of uncontrolled growth and the overcrowded, congested cities that emerged following the Industrial Revolution.

In a nutshell, the concept called for a series of small, planned cities that would offer improved housing and prioritisation of space, as well as designated areas of green around the city perimeters, allowing free access and recreational space for residents. Importantly, these belts of greenery weren’t allocated because of their beauty or for environmental preservation, but to improve urban life by creating more balanced cities and happier residents who would benefit from access to green spaces.

Howard’s ideas were brought to life in Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City— both of which still exist in England today. Architectural and engineering experts of the time celebrated the radial plan of Howard’s diagrams including his emphasis on creating a permanent girdle of open and agricultural land around the town.

The Garden City Movement also influenced Howard’s contemporaries at the London Society, who in 1919 produced the Development Plan for London, which called for the provision of green spaces in the city’s outer suburbs.

Then, in 1935, London County Council (LCC) pursued a Green Belt for the capital and in 1938 the Green Belt (London and Home Counties) Act was passed, enabling local authorities to purchase and protect land from development.

This Act also allowed landowners to enter into covenants, safeguarding their own plots under the Green Belt designation. In order to fully implement the Green Belt policy, the LCC embarked on a programme of buying up land to create a park encircling the capital, obtaining 8,000 hectares by 1939. Again, this space was intended to be publicly-owned and accessible and was purchased solely because of where it was—not because of its scientific value or environmental quality.

A few years on, the idea evolved further when the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act was introduced and formalised the updated purpose of the Green Belt: to check urban sprawl and protect the countryside from increasing urbanisation - purposes that are echoed in the National Planning Policy Framework we adhere to till this day in 2024.

Throughout the 1950s, local authorities were allowed to designate land as Green Belts within their Local Development Plans, with the Government at the time requesting that Green Belts be designated to resist further growth of built-up areas, to prevent the merging of towns, and to preserve the special character of towns.

What should be clear in this fleeting review of the Green Belt’s history is that it was never designed for environmental protection. While in the early days, it was about improving life for locals by providing recreational space, since then its primary goal has been to prevent urban sprawl and it has - crucially - never been about its outstanding environmental quality.

Green Belt designations have undoubtedly been successful in preventing our major towns and cities from facing issues of urban sprawl seen by many other cities worldwide, most notably those in the US. However, it cannot be denied this success has resulted in many knock-on social, economic, and environmental consequences.

In order to assess why the Green Belt has remained so untouchable in the face of manifold socio-political changes, let’s now debunk four widely held myths that shape public attitudes about the policy.

Here we go.

I’ll begin with the most enduring and powerful myth of all - that the Green Belt is, well, green. Though its name conjures vivid images of idyllic green countryside free for locals to enjoy as they please, the reality of the Green Belt is a little different.

Let’s take a quick look at the numbers:

While there is no denying that much of the Green Belt serves important planning purposes and should be protected, the reality is that Green Belt is not green in many areas. There is a large amount that is not as green as we are led to believe; for every rolling valley or meadow, there's an acre of scrubland.

Though many people believe that the Green Belt serves to protect wildlife, special landscapes, and historic assets, it’s important to make it clear that the Green Belt is not an environmental designation. Rather, the primary purpose of the Green Belt is to prevent urban sprawl and retain the openness of the countryside.

According to the National Planning Policy Framework, the Green Belt policy’s fundamental aim is to “prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open” and it serves five purposes.:

(a) to check the unrestricted sprawl of large built-up areas;

(b) to prevent neighbouring towns merging into one another;

(c) to assist in safeguarding the countryside from encroachment;

(d) to preserve the setting and special character of historic towns; and

(e) to assist in urban regeneration, by encouraging the recycling of derelict and other urban land.

As you can see, the policy isn’t concerned with environmental preservation; its chief purpose is to contain the expansion of cities.

But wait, if the Green Belt doesn’t protect sites of particular environmental beauty, then why aren’t there skyscrapers being built in places of genuine beauty like the Cotswolds?

Great question!

Areas of genuine historic, environmental, or landscape importance are already protected through other designations such as National Parks, Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), conservation areas, and sites of special scientific interest (SSSI) - we’ll talk about those a little bit later on in the piece.

The key takeaway? The ‘green’ part of the Green Belt is misleading; Green Belt land is designated and protected due to its location, not on account of its scientific value or environmental quality.

This is why I believe there should be more nuanced discussions regarding building on Green Belt land.

With this in mind, let’s now debunk the second myth.

As you’re no doubt aware, the UK is in the midst of a relentless housing crisis.

While the crisis is complex and can’t be pinned solely on one factor, what we can say is that one of the most substantial contributors is the severe housing shortage and the fact that supply is simply not meeting demand.

This imbalance has caused both real estate and rental prices to soar, with affordable housing virtually non-existent in many pockets of the country. In fact, at the time of writing, the average London home costs 12 times the average London income.

This shortage is tied to an overwhelmed planning system, population growth, slow build-out rates, and a lack of genuinely deliverable land.

That is where the Green Belt debate comes in. When low-value, well-located Green Belt sites are treated as automatically off-limits, the effect is to squeeze supply even further and intensify pressure in the very places where demand is highest.

In practice, refusing to release the least sensitive land does not protect communities from change. It often deepens the housing crisis by restricting the number of homes that may be delivered, prolonging shortages and locking out younger and lower-income households.

If the Government is serious about meeting housing need, it must be willing to focus development on the least sensitive land, including low-value parts of the Green Belt, rather than treating the designation as uniformly untouchable.

In my Sky News interview, I explain why the Green Belt is often misunderstood, why Grey Belt is intended to focus development on the right places, and how local opposition may slow delivery even when schemes are later approved on appeal.

With that context, the key point is simple. This is not about building over the countryside. It is about making smarter choices, using evidence to distinguish between Green Belt land that performs strongly against policy purposes and land that is already degraded, previously developed, or functionally urban.

An excerpt of Shelter’s summary of their 2016 report ‘When Brownfield isn’t enough’ read as follows: “Building on some bits of the Green Belt should be an option, if done right. Smaller, controlled release of appropriate bits of Green Belt land could deliver substantial numbers of new homes.”

Ultimately, as Shelter suggested in this report, developing parts - not all - of the Green Belt would offer a significant step in the right direction in meeting the needs of England’s growing population and remedying the current crisis.

At this point, a fair question is: what about brownfield land?

Brownfield has rightly been prioritised for years, but it is not a silver bullet. Some previously developed sites do support biodiversity, and even where they do not, the bigger issue is capacity. Brownfield alone has not been enough to meet housing targets, particularly in high-demand areas where most sites are already in use or already allocated.

So what would Green Belt development look like in practice?

Done properly, it would not mean carving up the most valuable landscapes. It would mean prioritising low-value, well-connected sites that are already dominated by hardstanding, fragmented by infrastructure, or previously developed. It would mean delivering a policy-compliant mix of homes, including affordable housing, supported by the right infrastructure and green space.

This direction also reflects the current Government’s ambition. Labour has set a target to deliver 1.5 million homes over this Parliament and has linked delivery to planning reform and a more pragmatic approach to low-value Green Belt land, often framed through the language of grey belt.

Now, let’s take a look at the third myth.

People are often surprised to learn that a large proportion of the UK’s countryside isn’t actually a part of the Green Belt.

As mentioned in our first myth discussing the overinflated ‘greenness’ of the Green Belt, there are vast quantities of important ecological sites outside of the Green Belt that are protected from development despite not having a Green Belt designation.

How are they protected?

By being designated as either Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), sites of special scientific interest (SSSI), or as National Parks.

As we’ve discussed, the primary purpose of the Green Belt is to contain urban sprawl - not to protect the countryside. Unfortunately - yet, understandably - there is an entirely erroneous conflation of the Green Belt policy with countryside protection, particularly from an environmental perspective.

Many well-meaning environmental groups contribute to the persistence of this idea, including CPRE, the countryside charity, whose literature often compounds the stated purpose of the Green Belt with the consequent functions that land within it can perform, such as important ecosystem services.

There is no doubt that this land offers vital climate change mitigation tools; it naturally contributes to cooling, reducing the heat island effect of major cities like London, and also fosters carbon storage, flood protection, and rainwater catchment.

We do not dispute these claims, nor do we dispute the importance of curtailing development in areas of aesthetic and scientific significance.

Where we do take issue, however, is with the logical fallacy that many of these reports rely upon: namely, that releasing portions of the Green Belt for controlled development is inherently at odds with ecological preservation efforts.

Now let’s take a look at the final myth, that Green Belt policy trends are standard practice.

Given its lengthy history, it’s commonly assumed that the Green Belt is a standard policy, indicative of usual English planning practice.

However, this isn’t the case.

England follows a discretionary planning system: instead of allocating sections of towns and countryside into zones that can only be used for a specified purpose, here we work on a case-by-case basis steered (but not generally determined in advance) by local plans. Planning documents at a neighbourhood, local, and national level are all in constant dialogue with one another, with decisions made according to both policy and precedent.

This system empowers local governments to accommodate changing planning needs, evolving in response to arising issues and adjusting policies which are no longer fit for local needs, while still adhering to larger regional and national planning strategies.

By contrast, the Green Belt operates as a zonal system. This was noted in a research paper by Dr Alan Mace, Professor of Regional and Urban Planning Studies at the London School of Economics.

In his paper, Dr Mace points out that the Green Belt alone operates as a zonal system. While all the other elements in it could one day be changed or replaced, the National Planning Policy Framework sets the Green Belt apart by anticipating that it will outlive local plans and their policies.

Dr Mace cites NPPF 2012: Section 85, which reads: “When defining boundaries, local planning authorities should satisfy themselves that Green Belt boundaries will not need to be altered at the end of the development plan period.”

The Green Belt is therefore uniquely considered a given and cemented into policy architecture as such – not only for the present but also for the future - despite its often direct contradictions to the dominant policy structures that make up the English planning system.

This information interacts directly with the other cultural, economic, and environmental logic that we have already explored to explain the Green Belt’s persistence. Looking forward, it also gives us a realistic sense of the substantial challenges that Green Belt reform efforts would be met with.

So there you have it: four lingering myths about the Green Belt that have persisted for far too long.

Ultimately, the reason I am so passionate about this topic is that I firmly believe the Green Belt is key to resolving the UK's growing housing crisis. The way we currently treat the Green Belt creates artificial scarcity around our most in-demand cities. When so much land is effectively taken off the table, supply is forced into a smaller footprint, land values rise, and house prices and rents are pushed higher. In plain terms, Green Belt constraints are a major driver of housing prices.

By releasing only a small percentage of low-value Green Belt land in the right locations, we could significantly expand housing availability for years to come and ease the upward pressure on prices. This would not trigger an overnight drop in house prices, but it would help stop them rising so aggressively.

Though the roots of the policy are well-meaning and certainly served an important purpose decades ago, the reality is that times have changed, and a policy this influential should be changing with it. As discussed, the Green Belt does little to preserve our natural environments. That was never what the policy has been about. Yet the way it is defended today often stands in the way of progress.

One of the primary reasons the policy has persisted for so long, and that countless governments have been too afraid to suggest reform, is the blind faith of Green Belt defenders. Though well-intentioned, many supporters misunderstand the fundamental purpose of the policy and neglect to acknowledge that opening up just some land in the Green Belt could make a huge difference in resolving the crisis that continues to plague this country.

Many of the Green Belt’s loudest supporters encourage building to go ahead on brownfield land. Brownfield should be prioritised, but as we’ve discussed, building exclusively on brownfield land isn’t enough to get the job done. There’s simply not enough deliverable brownfield in the places where demand is highest to cater for the overwhelming demand.

All in all, the point of this piece is not to suggest we tear up all Green Belt land across the country and build skyscrapers in its place, but rather that we adopt a strategic approach and release land that is of low environmental quality, making smarter use of sections of the Green Belt that lack genuine greenery.

Our team of Green Belt architects and planning consultants is fast earning a reputation as one of the country’s leading planning and architecture firms - particularly when it comes to Green Belt planning permission - and we know how to produce results that meet the expectations of the council while exceeding those of our clients.

We’ve done work on the few Green Belt exceptions that exist and have an established understanding of the Green Belt very special circumstances that can sometimes allow for development on the Green Belt, which makes us a go-to team for many landowners looking to bring their dream home design to life.

If you’d like to discuss your project in the Green Belt, please get in touch with our friendly team.

The Green Belt is one of the most contentious and misunderstood pieces of planning policy in England and it’s a topic we at Urbanist Architecture have a lot of experience working with. For this reason, we decided to pool our learnings and pen a book delving deep into the Green Belt from every possible angle.

‘Green Light to Green Belt Developments’ investigates the policy's biggest winners and losers, and explores its connections to climate change and the housing crisis, as well as what the future might hold, particularly now a new Labour government is in power. It also looks at the history of the policy and how it’s managed to endure while other policies have evolved and adapted with the times. Of course, it also identifies the exceptions and circumstances that exist for permitting development in the Green Belt, so you can better your chances of gaining planning permission.

We’ve written this book for anyone seeking a more rounded understanding of one of England's most debated urban planning issues, making it accessible to both industry professionals and the general public.

Whether you are a landowner in the Green Belt wishing to understand the potential for land value uplift or a developer planning to build new homes in the Green Belt, this book is an essential read. Order your copy now.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message