Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Most owners of a listed house are aware that making major changes to their home will be a bit more complicated than if they lived in any other kind of property.

But it’s easy to think that those restrictions only apply to the kind of changes that would be instantly visible to anyone walking down the street, and that more seemingly straightforward alterations - such as updating the windows - might be possible with little fuss.

That would be an unwise assumption. So in this article, we will explain what you need to think about when it comes to replacing the windows on Grade II or Grade II*-listed buildings, including how to find information about the listing and what your chances of being able to install double glazing are.

But first of all: if you think your home might be listed but are not sure, how do you find out?

Listed buildings are widely spread around the UK - there are probably a lot more than you think. The organisation in England that looks after the list is Historic England – they make it very easy to search for your home.

The list is called The National Heritage List for England and covers not only buildings but monuments, parks, gardens, and battlefields. The Historic England website has a simple-to-use search function: you can put in a keyword, postcode or list entry number.

You can also search via the map. Each historic site is indicated with a blue pin, with larger areas being covered by a green square. But just in case there is a key, filter and several view settings, to aid your search.

Click the pin and it gives you initial information of: name, designation type, grade and List UID (list number) and the link to that item's specific page. Designation type means a protected space is classified as either:

If you’re unsure of any words used, they also have an index page.

Sidenote: it’s also good to know if you live next to a listed building, conservation area or other heritage sites, because your proximity to them can impact your ability to get planning permission or be an influence on how conservative a design for an extension you need to go for.

If you bought the house, your solicitors should have alerted you to the fact that it is listed. But if you inherited it or have taken it over from another family member, you might be less sure. So let’s look at the factors that make a building likely to be listed.

The most obvious of these is the age of the building. Anything built before 1700 will be listed. A significant number of Georgian and Regency houses are also listed. By the time we get to Victorian homes, age no longer means rarity and therefore there has to be a historical or architectural reason why the building is listed. However, that shouldn’t be taken to mean that from the 19th century on, a building has to be unique or extremely special to be listed – vast terraces in parts of central London are listed on mass.

The more recent a building is, the more remarkable it needs to be to earn a listing. The British Library, completed in 1997 (although begun in 1982!) is Grade I listed. Even so, there are some 1980s flats and houses in London’s Docklands that you might be surprised are listed, especially when similar-looking buildings are busily being demolished.

The reasoning the Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport uses to make decisions on listings, following recommendations from Historic England, is:

1. Is the building of importance because of its design, decoration and craftsmanship? If so, it could be of architectural interest

2. Does the building act as an example of the nation’s social, economic, cultural and/or military history? That could make it of historical interest

3. Has the building been associated with historically important people or events? Then it has a historical association.

4. Does the building sit directly framing a square, terrace or model village? This would make it an architectural ensemble, which would be classified as having group value.

In summary, if your home is neither particularly old nor distinctive, chances are it’s not listed. And many of the more recent listed homes will be flats or on estates where individual homeowners aren’t responsible for replacing windows. But if you do want to make sure, it only takes a couple of minutes to check the list.

No, being in a conservation area is not the same as being listed. At the most basic level, the council has no planning control over what you do on the inside of a building in a conservation area, as long as you don’t change the use or split up into flats. But being in a conservation area does mean that you will be more restricted about what you can do with the outside.

Your home is in a conservation area because the council has decided the collective look of the buildings, streets and parks is worth preserving, even if that means a certain amount of inconvenience to the owners of homes and businesses. In theory, those owners should then benefit from living in an attractive and cared-for place, although we should say that isn’t always the case.

However, you only need planning permission to change the windows in a conservation area if the council has imposed what’s called an Article 4 direction blocking specific kinds of permitted development in that neighbourhood. You should be able to check this on your council’s website, although some make this easier than others.

Confusingly, there are also locally listed buildings. These buildings do not show up on Historic England’s list and there are actually no additional planning rules that apply directly to them. What local listing does mean is that if you do have to put in a planning application for one of these buildings, the council will be paying close attention to how it affects its heritage and character.

As unjust as it feels to some people, in Britain while you can own a piece of land or a building, the right to make changes to that land or to that building is held by the government. The government then lends owners the power to make a lot of those changes without permission or with straightforward permission via permitted development.

But in the case that your home is of historical interest, it’s classed as being of interest to not just you but also to the country and its history.

You find it interesting because you live there, but the government and/or your council find it interesting because of other people that have lived there and because of the other periods of time that your home has lived through.

It’s very much about the bigger picture.

If you’re still reading, we assume you own a building that is either listed or is in a conservation area with an Article 4 direction that states planning permission will be required for changes to windows and doors.

The question is why do you want to change your windows? Is it simply because either the glass or the frames are in bad shape? Do you want to upgrade the acoustics or thermal efficiency (eg, double or triple-glazed) or the way they look?

At this point, it’s useful to know that Historic England’s general advice on windows can be summed up as:

“Repair is better than replacement”

However, as we will explain, that won’t always be the case. Let’s start, though, with the refurbishment option.

While changes that could affect the historic fabric of a listed building will need listed building consent, many repairs will not need a sign-off from the council. When it comes to windows, the following do not require permission:

Let's be clear, listed window restoration, rejoining, and overhauling are also cheaper than replacement - and repairing often produces better results.

Consent isn’t generally required for any repairs to a listed building. However, the repair work should be as invisible as possible and not change the look of the windows in any way other than restoring them.

The crucial first question is: are your windows original? Guides like this are often written as if all listed buildings were magically intact after decades and often centuries of use. That, of course, is frequently untrue – many of them have been substantially changed over time. It follows that if the house was built in 1780 and the window frames have survived since then, your chances of getting approval to rip them out entirely are very low. But if your home dates from 1780 and the windows from 1980, then you are in a very different situation.

Again, if you don’t know, never assume. Appoint a heritage building surveyor to come and examine your property – they will be able to tell you if you have the real thing or a good later replacement.

If the windows are either an out-of-character later replacement or a bad pastiche, the council is reasonably likely to say yes to a sympathetic replacement. Having said that, there will be the odd occasion when the heritage officer decides that, say, mid-20th century changes were an important part of the history of the building and that those need to be kept.

If, however, the windows are original (or at least old and in keeping with the building), in order to get permission to replace them entirely, it’s most likely they will have to be in a state of irretrievable disrepair.

In that case, your planning officer is likely to allow for sympathetic replacements, meaning you will need to match the original materials and style.

This is seen as "protecting the character of the building".

For protected windows – listed or otherwise – you’re aiming to replace like with like.

The important thing here is not to think of this in broad terms. As in: “The old ones are sash windows, these are sash windows, that will do.” Or even, “The old ones have white-painted timber sashes, so do these, they should be fine.”

Essentially, there are so many parts of windows that it’s easy for one detail to get overlooked and for that one small detail to later become a huge thorn in your side. The construction of these windows needs to be matched like for like, from the hinges, opening type, timber and glazing thickness, as well as the ironmongery and accessories. This often will require a specialist window manufacturer to match your existing windows with the replacements. The council will be looking at all of these small details, as well as how it looks externally.

If you replace without permission, you could end up receiving an enforcement notice from the council ordering you to reverse the works.

You should always make sure you match what’s already there unless you have a strong argument provided by a heritage expert to justify a change.

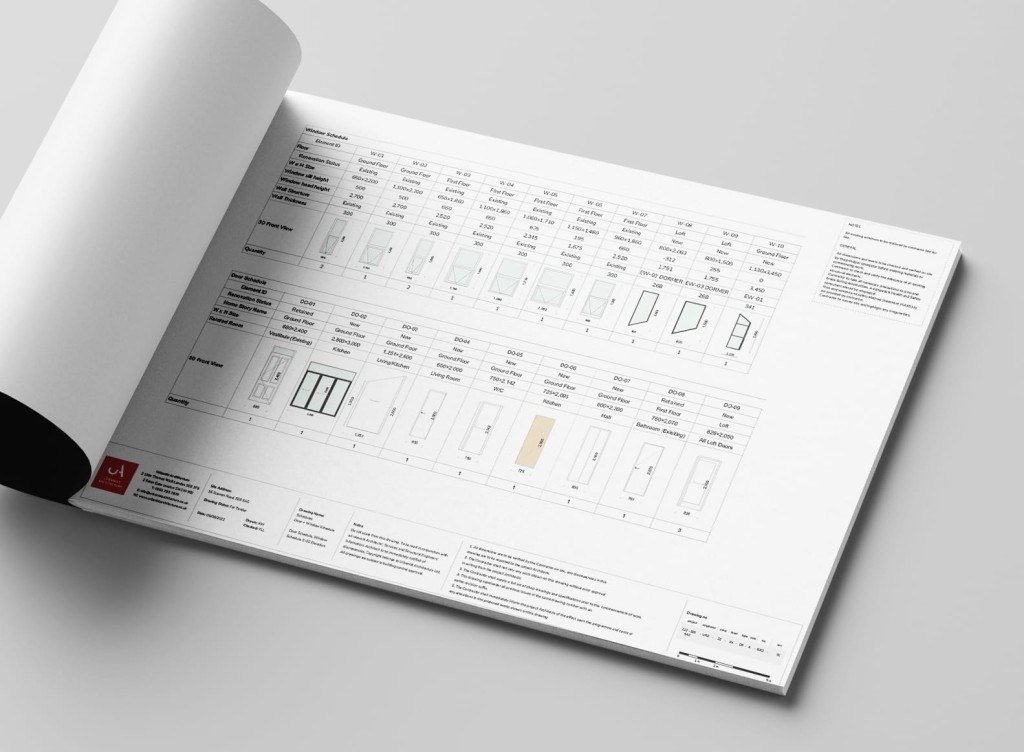

As we mentioned, the council will want to know exactly what is being proposed.

This is likely to include:

With a listed building, you will generally be applying for two (linked) approvals – planning permission and listed building consent. For homeowners, many councils allow you to put in a single application. Whether you submit one or two forms, a single planning officer will assess both of them together.

Most councils have straightforward lists on their websites of what is needed for an application. For example, Greenwich lets you know how many copies are required for physical submissions and at what point those documents would be required depending on the proposal type – it is particularly thorough. Even if your council isn’t Greenwich this checklist could serve as a good rule of thumb, so that you don’t get caught out and draw out your approval process further.

In theory, after the council has checked that you have submitted the right documents, the council has eight weeks to assess the application (although, in practice, it often takes longer). This includes a 21-day public consultation – any interested parties can comment, so watch out for that! Sometimes it’s a good bet to ask them for their opinions before submitting to see if you can smooth over potential problems or queries before they even get to the council.

It’s also a somewhat tricky proposition because you are trying to prove a negative – that nothing will change because of what you are doing.

For this type of application, you have to supply the following information:

The certificate itself will note the reasons that the works are lawful and have the date that approval was granted. It’s important to know that you cannot get this certificate for works that have already been carried out.

Submitting any misleading or untrue information also gives grounds for the certificate to be revoked – at any time. This includes out-of-date or inaccurate representations of the window/building on drawings or photographs, don’t leave anything out.

And remember, you might still need planning permission.

The main reason people want to change their windows is simple – to keep the building warm while using less energy. Indeed – and here’s the irony a lot of listed building owners find frustrating – for a non-heritage home, the council will usually insist on double-glazing as a minimum.

Windows also play a crucial role in keeping noise out (and in) and, of course, ventilation. Which is to say, there are many reasons why – if all things were equal – you might wish to have windows designed for the 2020s rather than the 1820s. However, if you somehow imagine that these are arguments that your council will never have heard before, and that they will be easily persuaded by them, you are mistaken.

Some specialist window manufacturers are able to design heritage-appropriate windows with an upgrade to double-glazed. Although these do not meet the like-for-like requirements, these are accepted by some councils if detailed correctly.

It’s easy to think of windows as being fairly straightforward – either single or double-glazed, sashed, grid or single pane, wooden, metal or PVC frames. But of course, the variations are almost endless.

For instance, here are a few window glass types:

They all have different characteristics and strengths. Your choice of glass depends on your specific window and what would be appropriate in light of its size, shape and depth.

For instance, glazing bars seem like such a small detail but various styles belong to specific periods, so you wouldn’t pick them by personal preference unless you could justify a point in time when they belonged to the building.

Take note of the depth of your window – the space it takes up within your wall – from inside wall face to outside wall face. The thing that usually causes variation in frame depth is the glazing, although sometimes it is the frames themselves that take up space.

In practice, this means that double glazing is often not an option for listed buildings – the gap between the glass is often 16-20mm but can be 100mm, which in many cases just isn’t appropriate.

Your glazing options will be individual to your building and its time period and precise history. Your listed building isn’t necessarily the same as your friend's halfway up the country or even in the next borough over.

The time period that a building belongs to is what dictates the methods used at the time to assemble it as well as the style of material, frame and brick choices. So for a 20th-century building, something like Fineo glazing – very thin vacuum glass – might be suitable.

PVC-u (also known as uPVC) stands for polyvinyl chloride un-plasticised – essentially construction plastic. It’s known for having good thermal properties, being strong and easy to produce. And over the last few decades, it has become a very common sight on the streets of Britain because it is the default frame for standard double-glazed windows.

Because of how uPVC windows are made they’ll always look different to traditional windows – which is one of the reasons they are generally unwelcome in listed window applications. Anyone who has had 1950s or 1960s metal single-glazed windows replaced with PVC-u will know how dramatically the amount of frame increases (and, correspondingly, how much the glass inside that shrinks.)

When it comes to traditional window types, PVC-u manufacturers have yet to be able to replicate the glazing bars (that strip of material between window panes) that are generally used on historic timber and steel windows.

The alternative: a single pane of glass with fake glazing bars. You won’t be fooled.

Steel or aluminium will often be considered inappropriate for pre-20th-century buildings.

For many listed buildings from the 1920s onwards, though, metal will be the only correct option. That might seem obvious, but it’s probably worth pointing out because while many listed buildings have been damaged by inappropriate modernisation, others have been compromised by a poor understanding of what “historic” means. This is the thinking that meant that in the 20th century, 18th-century cottages ended up having weird mock Tudor beams inserted into their walls. The same mentality has also meant all sorts of fussy window patterns being added to houses that originally had very simple windows.

The aim will always be to have windows that are appropriate for both the period and design of the building – so if it was built in the 1930s with Crittall windows, Crittall will be the correct choice again.

If the window frames on your house are timber, beware of thinking that all you need to do is make sure that the new frames are also made from wood. They still need to be the right kind of windows made to the right kind of accuracy and usually from the right kind of wood.

In 2009 English Heritage surveyed UK estate agents, revealing that: “replacement doors and windows, particularly PVC-u units, were considered the biggest threat to property values in conservation areas [...] 82% [of agents] agreed that original features added financial value to homes and 78% thought that they helped houses sell more quickly.”

Yes and no – replace-and-repair is often the smartest approach. Each of your windows is unlikely to uniformly be in an irreparable state - some areas will be worse off than others, which is exactly what you should tell your council.

You let them know that some areas need repair and others replacement but you’d prefer replacing certain ones. Planning officers are more likely to agree to a combination of window treatments.

If you want to introduce new materials, the wiggle room may be in the phrase ”to enhance”. If you suggest replacing in a way that is new but within the realm of the period of the building or windows, make the argument that you’re enhancing – adding to the heritage as opposed to taking away from it.

In this way, at the very least you’re starting a discussion about what you’re able to do instead of it being a clear-cut yes or a no. Be prepared some councils are only looking to preserve.

Within this discussion, you can talk about using textures or colours that might emphasise something new or different about the window - your aim is to create something different but not necessarily brand new.

There are both structural and legal perils that can come with works on listed building windows if not done right.

First, the structural dangers. Some older windows will have load-bearing frames so this has to be kept in mind if the frames are being removed. This is one of the many reasons why this type of work should be done by fully qualified people. Ideally, you would have both an architect and a structural engineer involved with this who could advise you on the need for structural support.

The legal danger is if you make changes to a listed building without getting the right permission, you have broken the law. In the worst cases, you could face an unlimited fine or two years in prison.

Many listed buildings have extensions or even wings that were built long after the earliest parts of the structure. Sometimes these will have been built to look as much like the original parts as possible, sometimes they will be clearly identifiable as a product of the time they were built.

For owners, this can sometimes make things easier, sometimes it can be a headache. If the council is fairly relaxed about what happens with the extension, you might be able to save some money, although the windows should always be generally in keeping. (There’s an award-winning extension and conversion of a listed building from the past few years that, if you go through the planning history, you will find that the initial application had PVC-u windows. The council gently steered them away from that idea – we don’t think the house would have ended up being praised on Channel 4 if the plastic windows had stayed!)

The worst-case scenario – more likely if the building is Grade II*-listed, but possible with some Grade II-listed ones – is that you end up having to deal with two specialist window companies: one to do the 19th-century windows for the main house, and the other to do 1950s windows for the extension.

This will depend on the grade of the listing, the history of the property, the condition and age of the existing windows and just what it is that you are aiming to do.

If you are replacing non-original windows (and only the windows) on a Grade II building, it could be that the window company can handle everything you need.

While if you want to repair original window frames, then the person you might be after is a carpenter with heritage training.

However, if your intention is to completely replace original (or at least fairly old) windows, talk to someone who has no vested interest in you committing to buying a product. That could be a heritage building surveyor, a heritage consultant or an architect with experience in dealing with listed buildings.

If you go on to make an application, a heritage consultant or an architect or planner with experience in this field can help you craft an argument to the council about why allowing the current situation to continue poses a greater risk to the preservation of the building than making the change, or perhaps use historical research to demonstrate why the current windows actually have little historical value. How could that be done? For instance, through archive research finding photos showing that the windows were once very different.

An architect can also act as your lead consultant – the person who gets quotes from different window manufacturers/installers and any other experts need (eg, a structural engineer) and translates technical terms to you, if that’s something you need.

Again, our advice is unless you have a great deal of experience yourself, or you are secure in the knowledge of exactly which elements of your home have historic value, then you should be getting at least some help from people with training and a good track record working with listed buildings.

In terms of specialist window companies, a single sash window refurbishment can come up to £700, while reglazing and restoration of a Grade II-listed building for a single sash window can come up to £1,750 per window.

In the case of a custom-made window, which will often be required, they’re often in the realm of £2,500-3,000 per window. And as the householder, it’s good to keep in mind that replacing a window is a larger cost than repairing one.

Urbanist Architecture has worked on many listed building projects, including a few that were specifically applications for window replacements, but more often more extensive changes with window replacement included. If you would like us to help replace or upgrade your windows, please get in touch today. And if you want to do something bigger to your listed building, for instance, change its use, we'd also be happy to help.

Nicole I. Guler BA(Hons), MSc, MRTPI is a chartered town planner and director who leads our planning team. She specialises in complex projects — from listed buildings to urban sites and Green Belt plots — and has a strong track record of success at planning appeals.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message