Read next

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

Every day, you’re bombarded with oversimplified takes on complex planning rules, emotive language about ‘vanishing countryside’, and selectively framed statistics. The truth has become hard to navigate.

It’s precisely this confusion I specialise in untangling. I help people navigate one of Britain’s most misunderstood planning policies: the Green Belt.

Over the years, I have examined tens of thousands of hectares that many assume are sacrosanct.

I have prepared numerous Green Belt and Grey Belt proposals from strategy to consent, defended well-designed proposals at planning appeals that some officers claimed would "destroy the countryside", and analysed hundreds of applications and decisions to see what actually stands up.

I have also co-authored Green Belt to Green Belt Developments, a book that traces the history of Green Belt policy and shows how professionals can navigate its complexities to deliver sustainable development through existing exceptions, special circumstances provisions, and the new Grey Belt framework.

Today I want to share what this work has taught me about the Green Belt, and why many common beliefs, often shaped by the media, miss the mark.

Quick note: if you're curious whether a specific site falls within the Green Belt, you can check using this interactive Green Belt map.

When we think of the Green Belt, we picture this: beautiful, open countryside that must be protected at all costs.

And yes, some Green Belt genuinely deserves protection. But the reality is more complex.

Look closely at this magnificent aerial view of a luxurious country estate. It features pristine tennis courts, an elegant swimming pool nestled amongst mature trees, and immaculately maintained gardens stretching across several acres of verdant landscape.

The Tudor-style manor house sits majestically at the heart of this pastoral paradise, surrounded by ancient woodlands that seem to stretch endlessly towards the horizon. Many of us would quite fancy living in such splendid isolation. If I asked whether this sits in the Green Belt, you’d probably say yes, wouldn’t you?

Add this to the set and reserve judgement. Here is a scarred and excavated parcel of land in Ealing, where churned earth and temporary fencing reveal what appears to be an abandoned construction site or demolition area.

The muddy terrain is littered with debris, overgrown with weeds, and bordered by a makeshift path that speaks of urban decay rather than countryside tranquillity. A fresh frame, same dilemma. Green Belt or not?

What about this desolate wasteland in West London, where crumbling concrete structures and rusted industrial machinery create a post-apocalyptic landscape of abandonment?

Piles of rubble and construction materials are scattered across the site, whilst graffiti adorns the deteriorating walls of what once might have been a thriving industrial complex. We’ve moved on, but the question remains. Pick a side: Green Belt or not?

Now, let’s zoom right into the city’s edge. Here is a bustling hand car wash and valeting centre next to Tottenham Hale station, where the constant hum of urban activity fills the air.

Rows of vehicles await cleaning under the bright commercial signage, whilst the industrial backdrop of warehouses and transport infrastructure creates a distinctly metropolitan atmosphere far removed from rolling green fields. Make the call now: Green Belt or not?

Add it to the line-up before deciding. Here is an aerial view of a site in Tottenham (N17) which reveals a roadside garage, MOT testing centre and tyre depot, where a canopy-topped forecourt is carpeted with stacked tyres and low-slung workshops spill into a cluttered service yard.

Vans, parts and pallets crowd the access, while containers and ad-hoc additions creep towards the treeline at the site’s rear. Industrial grit meets green fringe; the boundary blurs. The lens has shifted; the question remains. Green Belt or not?

Finally, this collection of six aerial photographs captures sites from across Britain, each showing different landscapes that challenge our preconceptions about what constitutes protected countryside.

From quarries and treatment works to industrial facilities and excavated land… These aren’t meadows. They’re quarries, sewage works, industrial yards, and waste facilities. So, Green Belt or not?

Here's the truth: Every single image above sits within the Green Belt. Yes, you were onto it from the start.

If these images don’t reveal the complex reality behind our supposedly pristine Green Belt boundaries, what will?

But that’s just the beginning. Read on to see why the question isn’t whether we should build in the Green Belt, but where and how well we should do it.

Ask a cross-section of people what the Green Belt is and you’ll hear a familiar script. They picture endless green fields and trees: a continuous ring of countryside wrapping our cities, where building is simply off-limits.

In their minds, it’s the place you go for a walk, the lungs of the metropolis, a fixed line on a Green Belt map that holds back concrete.

The label does a lot of work: ‘Green’ reads as nature, fresh air, and tranquillity; ‘Belt’ suggests a firm strap that holds urban sprawl in check. Put together, the public often treats it as an environmental designation by default.

Most people’s understanding is broad-brush rather than technical. They know ‘you can’t build on it’, but aren’t sure who decided that, when boundaries were drawn, or how they change

The nuances rarely feature. Terms like ‘openness’, ‘permanence’, and ‘sprawl’ sound like common sense, so assumptions fill the gaps.

Some people think that if it looks green, it must be within a Green Belt designation. If it sits beyond the suburbs, it must be protected. Parks, heaths, and nature reserves get folded into the same mental category.

They also commonly conflate Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONBs) with the Green Belt, although their purpose and coverage differ.

In the age of the digital dimension, where critical thinking and informed debate are often drowned out by noise, these assumptions thrive. They don’t form in a vacuum.

Consequently, today’s news ecosystem amplifies low-quality coverage, and many readers struggle to separate reporting from opinion, becoming vulnerable to manufactured disinformation that plays on identity and emotion.

The result is ‘truth decay’: People disagree on basics and trust widespread Green Belt misconceptions over facts.

Public reaction to media stories shows how firmly these perceptions are held. See, for example, Revealed: The 20 areas most at risk from Labour’s house building boom, an article I contributed to, which attracted hundreds of comments within just 12 hours of publication.

Nowadays, commentary in many outlets can read as negative, but that’s not the real issue. What we’re seeing is people treating the Green Belt as a moral imperative, something to be defended at all costs, so the debate becomes ethical first and logical second.

That intensity turns the Green Belt into both a shield for nature and a hard barrier to growth, regardless of the planning tests that actually apply.

This isn’t simply a fake-news problem; it’s a framing problem. Headlines, maps and emotive imagery, often steered by political and campaign interests, define what counts as “nature” and “threat”, setting the terms of debate long before planning policy is considered.

In short, the Green Belt is routinely miscast as pristine countryside, neatly uniform and absolutely untouchable. The issue isn’t the existence of green spaces; it’s the habit of treating the Green Belt as a nature designation or beauty contest.

No. The Green Belt is not a conservation badge. In reality, it was never about ecology or prettiness.

In planning terms, it’s a designation judged by how land performs against specific purposes, rather than its ecological richness.

In my live Sky News interview, I explained why “green” does not automatically mean protected countryside, and why the Grey Belt approach is intended to focus development on the right places — unlocking low-value land near infrastructure while safeguarding the landscapes that truly matter.

If you take one point from that, let it be this: the Green Belt’s status is not decided by how a site looks, but by how it functions in planning terms.

That is why you often find farmland, scrub, quarries, or golf courses within it, with little or no public access. On the other hand, biodiversity is protected through other designations such as SSSI or Local Nature Reserve.

And this matters for Green Belt planning permission because a common misconception is that anything that looks rural must be preserved at all costs. In reality, some Green Belt sites make a limited contribution to the policy’s purposes and may even be brownfield or degraded land.

Within that policy framework, “openness” is a specific planning concept: it concerns the presence and permanence of development, not how green a place appears. A site can look pastoral yet still contribute little if it is served by urban infrastructure, dominated by hardstanding or functionally urban in character.

The Green Belt is a planning tool to keep land open and steer where growth happens. It serves five purposes:

Which is why, in practice, every parcel should be judged on its contribution to these Green Belt purposes.

Some land forms create critical gaps between settlements or act as a strong boundary that resists sprawl, so its contribution is high. Other land is already developed, fragmented, or visually and functionally urban, so its contribution is limited.

In practical terms, where councils cannot meet housing needs, national policy expects them to assess reasonable options and, where justified by evidence, review Green Belt boundaries through the local plan.

In other words, good plan-making protects where contribution is greatest and directs change where contribution is lowest, while strengthening boundaries, improving performance, and delivering the homes communities need.

Grey Belt, introduced in the new National Planning Policy Framework, reflects the Government’s drive to accelerate housebuilding through focused, evidence-led planning.

It identifies parts of the Green Belt that are previously developed or of low spatial value land that do little to advance the Green Belt’s core purposes. Development in the Grey Belt is not “inappropriate” where the four tests in paragraph 155 are satisfied. These are:

Since the policy’s arrival, there have already been dozens of successful Planning Inspectorate appeal decisions on Grey Belt schemes.

In many of these cases, planning inspectors have made it clear: yes, these sites are in the Green Belt, but they don't actually serve its purposes like preventing urban sprawl or protecting countryside. That means they qualify as Grey Belt under the NPPF’s requirements and PPG guidance for Grey Belt, and can be developed appropriately.

Although the new rules for Grey Belt is straightforward, there's still a gap between what national policy says and how some local authorities apply it. The practitioners like myself are frustrated that planning inspectors are approving most Grey Belt appeals, yet many councils still refuse applications

The result?

We're missing opportunities and creating unnecessary delays. Instead of directing new homes to the least sensitive land and safeguarding the genuinely valuable Green Belt, we're forcing developers through costly appeals.

We could be strengthening long-term boundaries through better design, landscape enhancements, and improved public access. But instead, we're stuck in this cycle where sensible development gets blocked at the local level, only to be approved months (sometimes years) later on appeal. It's inefficient, expensive, and helps no one.

The numbers tell a story politicians prefer to avoid.

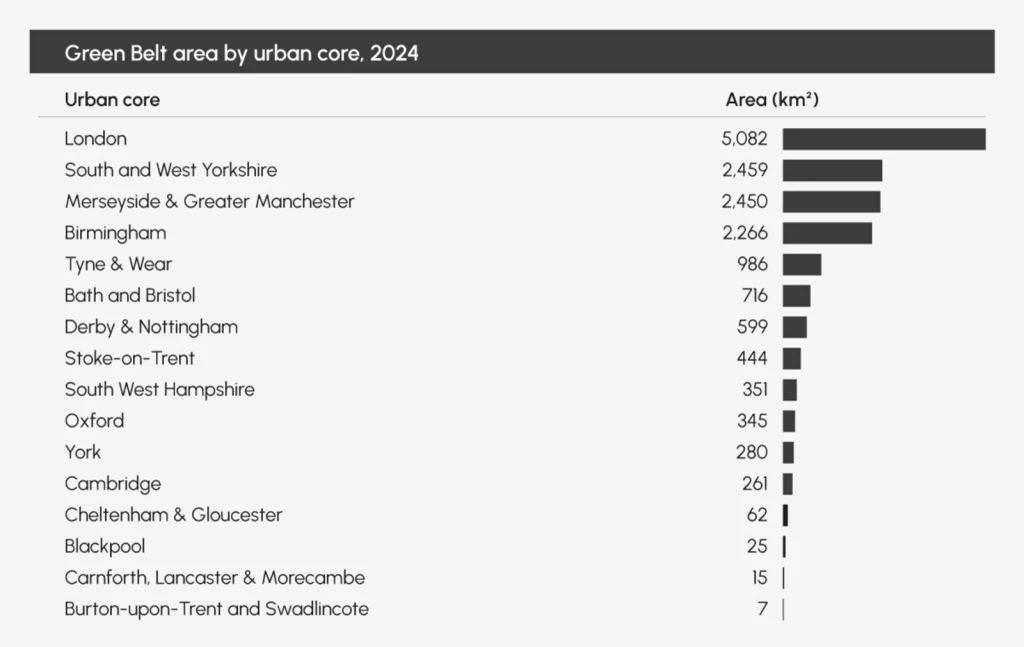

The largest Green Belt sits around London (over 5,000 km²), followed by substantial belts around South & West Yorkshire, Greater Manchester, and Birmingham.

Here’s the contradiction: these are precisely the places with the sharpest housing need, so our biggest belts ring the very cities where demand is highest. In effect, we’ve wrapped our most economically successful urban areas with the largest protected buffers.

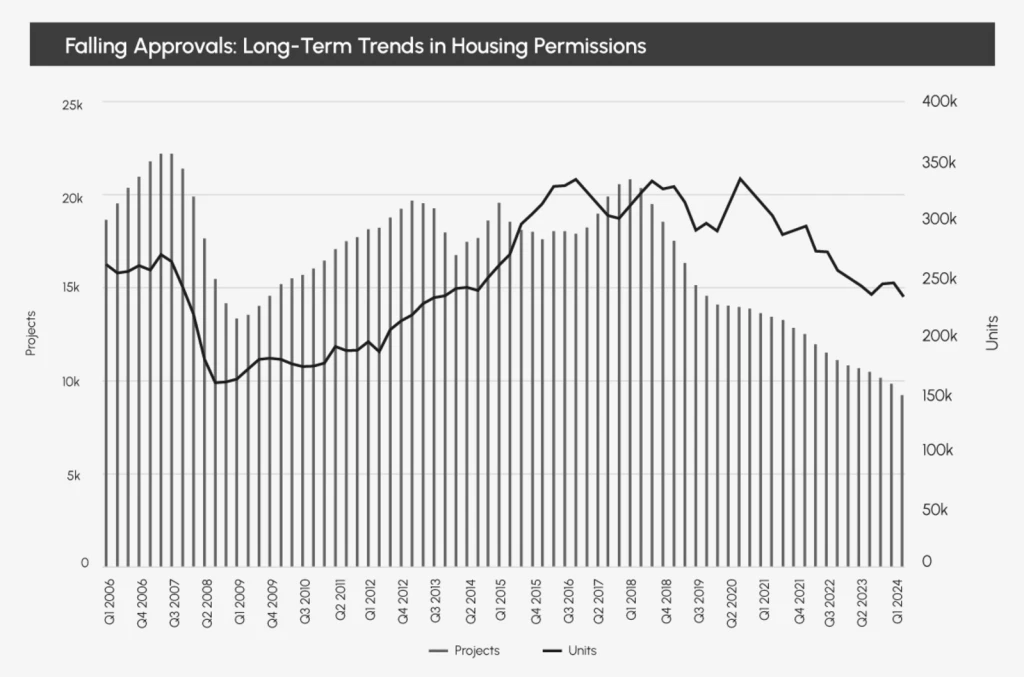

Meanwhile, housing delivery keeps sliding. The official statistics show that planning permissions for new dwellings slid to a 13-year low, with a 17% year-on-year decline.

Fewer approvals mean fewer homes, which forces demand beyond Green Belt boundaries, lengthens commutes, and inflates prices. The trend has been downward since 2018, compounding the pressure.

We’re currently building about 221,000 homes a year against a need of 370,000+, leaving a shortfall of roughly 149,000 annually.

To put that gap in perspective: if general inflation had risen as fast as house prices since 1971, a chicken would cost £51.

Without change, we entrench a system that favours asset-holders over aspiring households, locking in inequality and suffocating economic mobility.

The planning system must serve people, not protect outdated policies for tradition's sake. At Urbanist Architecture, we support reform, delivering high-quality homes in appropriate places whilst protecting landscapes that truly matter.

At last, new Green Belt rules make this intelligent approach viable. For 70 years, we treated all Green Belt identically, whether genuine countryside or derelict car parks. Now we can distinguish between them and build homes where it makes sense.

The evidence is overwhelming: much of our “Green” Belt simply isn’t green. We can either go on protecting quarries, golf courses, and car washes while families struggle to afford a home, or we can embrace evidence-based reform that serves both housing need and environmental protection.

And while brownfield should be the first port of call, it is not mathematically sufficient to meet demand on its own. Making matters worse, brownfield sites are often more expensive to develop due to contamination, infrastructure needs, or the complexity of the site. On any honest reading of the data, the numbers don’t add up without carefully targeted change on the least sensitive Green Belt sites.

The choice is clear. If we plan carefully and give developers the right level of certainty, homes could be built relatively quickly. The key is to unlock sites that are genuinely ready for development and make sure schools, transport, and services come forward at the same time. With clear boundaries, good design, robust master planning and the right infrastructure in place, we can create connected, walkable communities that respect their setting and truly meet people’s needs.

Urbanist Architecture’s founder and managing director, Ufuk Bahar BA(Hons), MA, takes personal charge of our larger projects, focusing particularly on Green Belt developments, new-build flats and housing, and high-end full refurbishments.

We look forward to learning how we can help you. Simply fill in the form below and someone on our team will respond to you at the earliest opportunity.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

The latest news, updates and expert views for ambitious, high-achieving and purpose-driven homeowners and property entrepreneurs.

We specialise in crafting creative design and planning strategies to unlock the hidden potential of developments, secure planning permission and deliver imaginative projects on tricky sites

Write us a message